It’s 95 degrees, a river tumbles through the remote Belizean wildlands. I am lying facedown wearing loose white pajamas a few feet from its banks, as a Thai woman named Pranee steps all over me. My skin flattens and bones complain. She hoists one leg up, drives her heel into my tail bone and pushes harder, driving my heel to the sky. I wonder if I’ll break in two, or perhaps into three. Sweating and stretched, but strangely relaxed, my mind turns in its delirious state to Francis Ford Coppola, bearded patron saint of indie filmmakers and, perhaps more incongruously, my host.

For the thatched hut that constitutes the spa as well as the river that runs alongside it; the graceful main lodge; two pools; three restaurants; and 20 cabins all belong to Blancaneaux Lodge, one of the filmmaker’s five resorts scattered across the world. (Two are in Belize; one in Guatemala; one in Italy; and one in Argentina.) Blancaneaux is nestled into a steep hill on the banks of the Privassion Creek in the heart of the Mountain Pine Ridge Forest, located in the Cayo District of western Belize. It is an unlikely oasis in a truly wild part of the world owned by an unlikely innkeeper. If, like me, you grew up on a steady diet of watching and rewatching Apocalypse Now, Coppola’s most audacious work, augmented by multiple viewings of his wife Eleanor’s 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness on the nutso making of the film — supplemented by repeated readings of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the tale on which the movie is loosely based — one can’t help but wonder if this here, this idyll, is part of a crazy real-life Coppola set. Which, I suppose, would make him Kurtz, the deranged captain mad with Promethean power… or perhaps it is I who is lost in the jungle, estranged from humankind and given over to his own darkness.

Craaaack.

A few vertebrae give in to Pranee’s pressure. My neck twists back and I fall into a deep sleep.

A few days earlier, after just one hour in the country, I’m sitting on the shaded veranda at Cheers, a sprawling restaurant alongside the Western Highway, about 30 miles from Belize City, halfway to Blancaneaux. White-necked jacobin hummingbirds flit around the mango trees in the yard, and José, my driver, is explaining how to kill a cow. “I just walk up behind them, nice and gentle, with the knife in my hand,” he says, with a thousand-kilowatt smile and his lilting Belizean accent. “The knife goes in — fwap! — and out. They’re dead in three minutes.” He pours some Marie Sharp hot sauce onto his plate of rice and beans, Belize’s national dish, and continues. “The blood squirts the length of the table!” My plate also beckons but, suddenly, I’m not quite as hungry. José, like many of the guides I meet, is friendly, absurdly knowledgeable, and has a side hustle. His happens to be working as a traveling butcher for many of the Mennonite families who moved to Belize from Canada in the 1950s and ’60s and who have settled in various enclaves around the country. That one will almost certainly pass horse-drawn carriages alongside the highway, driven by bearded and sun-toasted farmers wearing 19th-century dress, speaking an obscure 17th-century Prussian dialect, is just one of Belize’s many wonders.

After lunch and the impromptu tutorial on slaughter, we head back on the road. Blancaneaux Lodge is tucked high up in a mountain range in a hard-to-reach valley called, fittingly, Hidden Valley. The road there, Chiquibul Road, was treacherous and largely unsealed until just last year, when in an ultimately failed attempt to curry favor with the locals, the ruling party finally approved its paving. “We used to call it a free massage,” laughs José. Surely when Coppola first took the journey in the early 1980s, it must have been even more dangerous. We rattle past citrus plantations — some natives say many oranges marketed as Floridian are actually Belizean — and fields where cows, blissfully unaware of a butcher in their midst, graze contentedly. We wind through the jungle, past turnoffs for tiny towns like San Ignacio and San Antonio, until we make a hard right. The road gets smaller and smaller until it’s dirt running alongside a dirt airstrip and then suddenly it’s paved and there’s a thatched roof reception area, a pitcher of water with flowers floating in it to drink, and refreshing moist towels nearby. These things signify our arrival at Blancaneaux.

At the tail end of filming Apocalypse Now, an ordeal that stretched over two years, caused vast overruns, a heart attack for Martin Sheen, and multiple nervous breakdowns for Coppola, the director needed a vacation and he wanted to buy a vacation house in a part of the Philippines known as Hidden Valley. (The film takes place in Vietnam but was shot, with the help of Ferdinand Marcos, in the Philippines.) As Bernie Matute, the general manager of Blancaneaux, tells me, his wife discouraged the purchase, telling Coppola there’s no way he was going to schlep from California to the Philippines with any regularity. Wisely, he acceded. A few years later, when he was visiting his son Gio in Belize, he met a larger-than-life Belizean chef/author/politician named Ray Lightburn, who, upon hearing that Coppola was in the market for a hidden valley, told him of one in Belize of the same name. Coppola duly flew out to the tiny airstrip in the middle of the trees, clambered out of the plane, and jumped into the creek. He saw a For Sale sign and was sold.

That what was once a dilapidated lodge is now this Edenic compound is testament to Coppola’s world-making ability. The vertiginous hillside is neatly mowed; the cabins, with their cathedral-like thatched roofs and large mosquito-netted beds and tiled showers, gleam, like some primitive Versailles. There’s a conch in each room called a shell phone, by which one can reach the front desk. Who knew Coppola is the king of dad jokes? There are three restaurants, one of which — the Montagna Ristorante — serves undoubtedly the best penne with meatballs in Belize. It’s an old Coppola family recipe.

Of course, this all took work. For a decade, the Coppolas used the property as a family vacation home. With no running water or electricity, Coppola contracted a Canadian hydroelectric concern to outfit the place with turbines. After celebrities like Quincy Jones encouraged him, he opened it as a resort in 1993. Now a staff of about 50 keep the 70 acres tautly idyllic. Upon arrival, I immediately took to my deck to gaze at the creek and search for traces of Kurtzian insanity. There is, after all, something mad about taming these dense trees, imprinting onto the wildness an artificial hydropowered oasis: the neat gravel walkways and the perfectly serene pool, which is a square of azure on the lush lawn. But all that comes back are whispers of comfort. Slightly disappointed, I soothe myself by the firepit with a potent glass of Jaguar Juice — rum plus a local liquor made with craboo — as a local band plays plaintive ballads in the Jaguar Bar.

The next day, I awaken hungry for adventure. One could, I suppose, rest at Blancaneaux, lounge poolside, and check email. (I admit, I did much of that too.) But the lodge is the ideal base for quasi-heroic activity. One of them is horseback riding into the reserve. So after a breakfast of fry jacks, a sort of fried dough pocket, I head to the Blancaneaux stables and to Diego, my guide. Soon we’re off, me wearing a silly helmet; Diego not. The woods around us were once dense with Caribbean pine but, in the early 2000s, a pine bark beetle epidemic ravaged the drought-weakened forest, destroying nearly 80% of trees. Today it’s lush enough, though the same climate change that doomed the trees is all too present, lurking in long periods of drought and record-high temperatures. As we lope along, red wing grasshoppers the size of mice are flying like little dandies on their way to meetings. Sandpaper plants line the path, and wild oregano scents the air. Diego points out termite nests and the sweet smell of black ants. Tapirs live in this preserve, but we see only tracks. After 45 minutes, we tie up our horses under a pine tree and hike down the wooden stairs to a waterfall. On weekends, he tells me, the spot is crowded with local families on picnics. But we’re the only ones here today. We change into bathing suits and swim against the current to the base of the waterfall. Perched on rocks, I look through the mist to see the world alight with rainbows. I was searching for an Apocalypse and came to Paradise instead. Phooey.

Luckily, there was still time. Have you ever eaten mixed greens in the moonlight as happy families buzz around you like mosquitoes and mosquitoes buzz around you like harpies and all the choices of your life crash upon you like waves on a rocky shore? Nothing quite highlights one’s own solitude than being alone in a crowd at a luxurious retreat. It probably doesn’t help that my nose is buried in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. One night, while sitting on a hay bale at the Garden Spot, sipping a rosemary mojito among picturesque rows of Tuscan kale, carrots, onions, and lettuces at the property’s garden, I’m surrounded by two families seizing the last shreds of summer. Jason, one paterfamilias, a doctor of Chinese medicine, is with his wife and their two teenager kids, one of whom is friends with Caleb, who is there with his father, Dan, a big poobah at some talent agency in Los Angeles. I stew misanthropically, begrudging both families their happiness, and ruminate on the path that led me to lonesomeness. Aha, I think, in some perverted self-schadenfreude, I’ve found my misery at last, and all I had to do was look inward. But then Jason invites me to join the group for dinner, which I do, and my resentment melts away. Dan tells me about the Barolos he loves, Jason about ginseng, as the kids inquire about my tattoos. It’s not my family but it is a family — two, actually — and it’ll do.

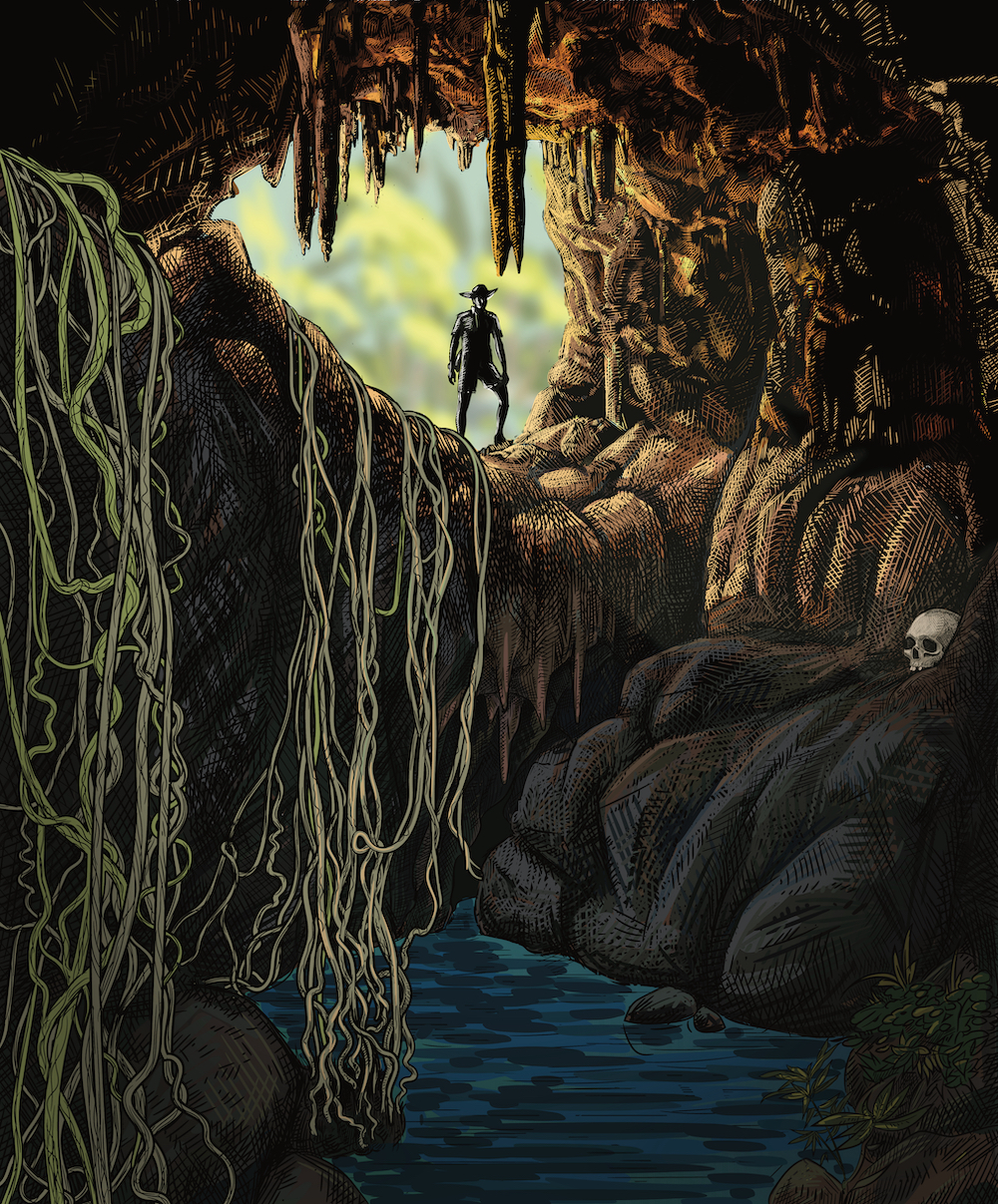

Francisco Reymundo loves Jeep Cherokees and has a plan to buy them in Florida and drive through Mexico to resell in Belize. He is also one of the only 30 or so guides licensed to take tourists into the ATM, the Actun Tunichil Muknal, a complex of caves discovered in 1989 and once used for Mayan sacrifice, located near Blancaneaux. Francisco picks me up from the gates of the resort in a white Cherokee — “I bought it for a few hundred dollars!” — with a crack through its windscreen. We head back to the coast, stopping for barbecue chicken and rice and beans from a guy standing at a drum grill outside his house. We bump along fields of corn and soybeans. “These are all owned by the Mennonites,” says Francisco. “They’re expert farmers.” Eventually we come to a gate manned, if one could say that, by a sullen 12-year-old boy. A sign says it costs 20 Belizean dollars ($9.90 USD) to enter, but it’s just for show. Francisco simply nods and the boy waves us through, with no Belizean dollars exchanged. The trail to the mouth of the cave is about a mile through dense forest. Snakes weave ahead of us as we traipse into and out of streams, holding on to a rope so as not to be swept away by the current. Eventually, we’re at the mouth of the cave. We don headlamps and life vests and swim in the dark clear waters. We’re the first ones in and all is silent except for the sound of our feet slushing through the underground stream. When we stop, all sound stops. When we turn off our lights, all is primordially dark. Francisco goes ahead of me, warning me of slippery rock faces and swordlike stalactites. Deep we go and deeper still until, in the furthermost chamber, he bids me remove my shoes. We scamper up the rock to a large chamber, scattered with Mayan pottery. Francisco leads me deeper into the heart of darkness, up a rickety ladder and into the sanctum sanctorum. And there I finally find what I’ve come to the jungle for. A skeleton, a victim of human sacrifice some 1,100 years ago, lies neatly on the floor before us. Her bones, covered in calcite, are cemented to the floor and sparkle as if bejeweled. Near her body is another skeleton, this one bound with cord long decayed. It too glisters under the light of our headlamps. Finally, I’ve found it. The horror, I whisper happily, the horror.