In the spring of 1949, Lady Rothermere, later Mrs. Ian Fleming, threw a formal ball to brighten the spirits of gray, postwar London. The Queen Mother (then still on the throne as Queen Elizabeth) was there, as was Princess Margaret, who, toward the end of the evening, startled everyone by grabbing the microphone from the band leader and instructing them to play Cole Porter songs, which she proceeded to sing in her notoriously high-pitched voice.

She was applauded by all the doting ladies sporting their family jewelry, with the men in their white ties and black tails, and was just launching into a warbly, off-key rendering of “Let’s Do It” when there came, from the back of the crowded ballroom, the sound of thunderous booing.

The band stopped. The princess reddened, gathered her crinolines, and fled the room, followed by her ladies-in-waiting. Among the guests that night was novelist Caroline Blackwood, who turned to the nearest man in white tie, his red face made apoplectic by rage.

“It was that dreadful man, Francis Bacon,” he thundered. “He calls himself a painter, but he does the most frightful paintings. I just don’t understand how a creature like him was allowed to get in here. It’s really quite disgraceful.”

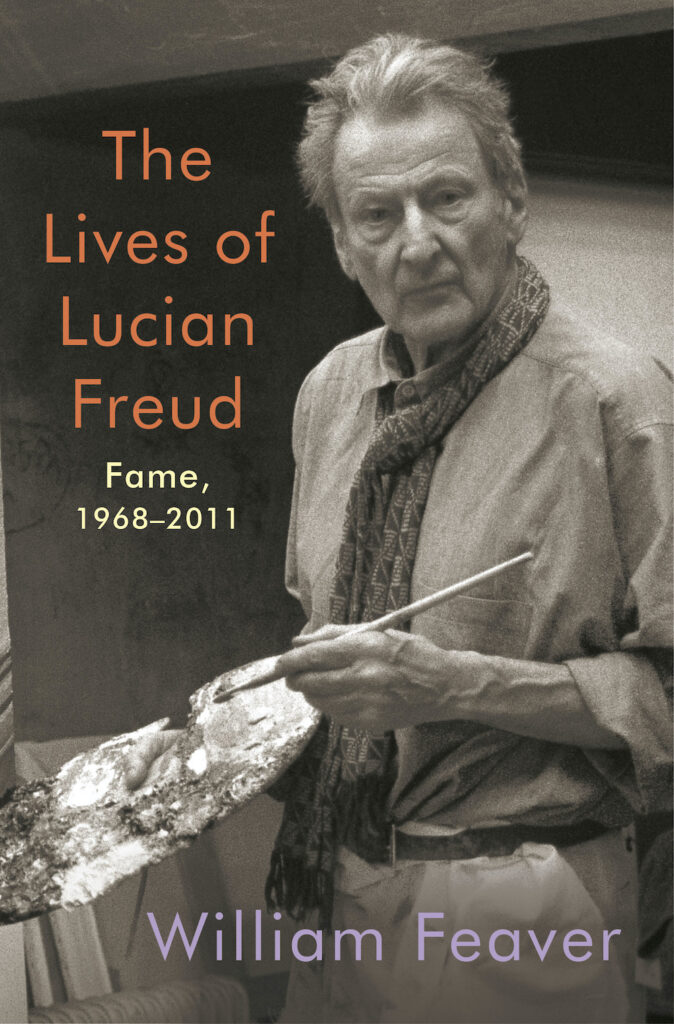

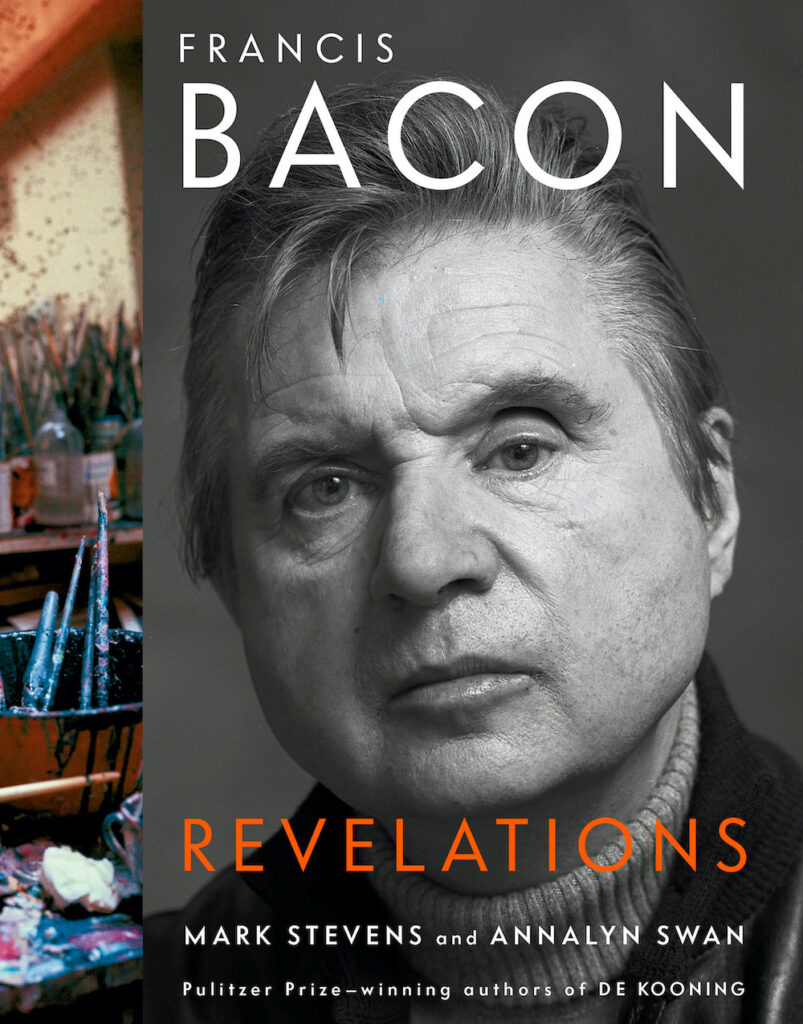

Bacon was there at the invitation of his friend Lucian Freud, whom Blackwood would later marry. As two monumental new biographies — Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s Francis Bacon: Revelations and Williams Feaver’s second and final installment of The Lives of Lucian Freud, covering the years 1968 until his death in 2011 — make clear, no two men would do more to revitalize figurative painting in the postwar era.

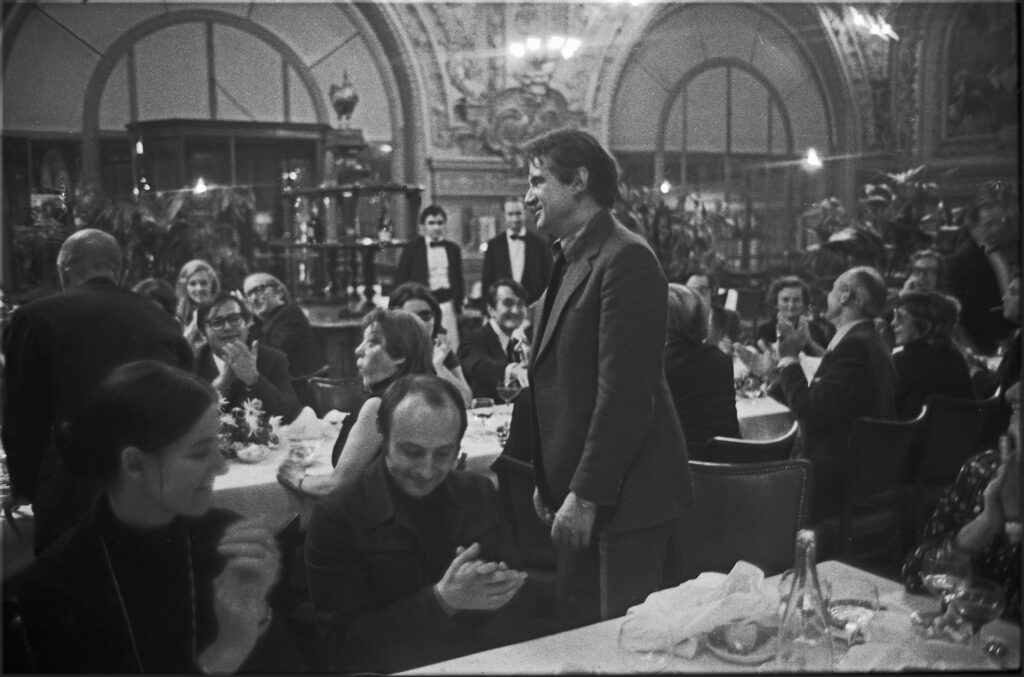

Image courtesy of The Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman ImagesEmerging from the bohemia of bombed-out Soho, the two painters, both in thrall to the flesh in an era smitten with wan abstraction, were virtually inseparable for much of the ’50s and ’60s. Blackwood said that she dined with Bacon pretty much every day of her marriage to Freud.

Most mornings Freud would drive to collect Bacon from his flat in his Bentley and head off for breakfast at one of the small workmen’s cafés at Smithfield Market. This was often followed by lunch at Wheeler’s on Old Compton Street or the Colony Room on Dean Street, the notorious, cramped members-only drinking club managed by the Gorgon-like proprietor Muriel Belcher, where Bacon, ebullient and impeccably mannered in black leather, would wave for champagne as he took his seat amid the Gitanes fumes and drunken invective.

“It was like being at the theatre… telling stories, and being absolutely scandalous and looking fantastic, and attracting attention and showing off,” Annie Freud, one of Lucian’s numerous daughters, told Feaver.

“Theirs was a deep love… I’ll tell you something that dad said about Francis that was so lovely. He said he had the most sensuous forearms. That is lover-like, isn’t it?”

Alert and shy but mercilessly direct, and fine-boned like a small bird of prey, Freud was 13 years the junior of Bacon, who had started painting late at 30, and whom he looked up to as the “wildest and wisest” person he had ever met.

Born to a wealthy Midlands family in Dublin, Bacon had swapped out Edwardian aspirations, tweed suits, and fox hunting for a life of what he called “gilded squalor” amid the rubble of postwar Soho, carrying with him an aristocratic disdain for money — treating sums both large and small with the same fabulous contempt.

“Francis opened my eyes in some ways,” said Freud. “His work impressed me, but his personality affected me.”

Introduced by Bacon to the roulette wheel, spun in late all-night sessions at his studio den, with his longtime nanny Jessie Lightfoot acting as a bouncer, Freud quickly became enamored of what Bacon called “the sensuality of debt.”

“Lucian, who was never very generous in the years I knew him, would run after Francis with great wads of banknotes and give them to Francis to go gambling with,” said one of Freud’s lovers, Anne Dunn. “Lucian was never a gambler until his relationship intensified with Francis… he’s retentive.”

Bacon, too, acted differently around his young protégé.

When Freud showed up at the Colony Room, Bacon cut back on the queening — all the cries of “daughter” and “duckies” in his fluting high voice — and huddled down with Freud to discuss Giacometti, Velázquez, and risk. Most evenings, Freud, after a prolonged session on the one-armed bandit slot machine, would peel off to continue work on his painstakingly executed canvases through the night, while Bacon continued gambling or in pursuit of cathartically cruel one-night-stands with sailors.

Freud fretted over his friend’s bruising penchant for rough trade, at one point taking George Dyer, the cockney homme fatal whose antics included planting cannabis in Bacon’s studio and tipping off the police, up to Scotland to dry him out.

“I know it annoyed him,” said Freud. “It was a bit like interfering in marriage rows.”

Bacon was equally bewildered by Freud’s hobnobbing with aristocrats. The Berlin-born Freud — whose family emigrated to London in flight from the Nazis in 1933, five years before his eminent grandfather, Sigmund, followed from Austria — had a remarkable ability to flit between the betting shop and Princess Margaret’s set, on whose patronage he relied for his portraits, and whose ruthless candor he admired.

“I don’t mind being on no terms or bad terms,” he once said. “I just don’t want to be on false terms.”

At one point he came close to painting a portrait of Princess Diana — “a great, great, great wonderful idea,” Lord Goodman told the princess’s secretary. “But I shouldn’t leave her in the room with Lucian.”

Bacon dismissed such activity as the worst kind of social climbing. When Freud was named Companion of Honor in the queen’s 1983 birthday honors list, Bacon took the opportunity to boast of his own status as earl manqué, claiming to have turned down two offers of a knighthood.

“I came into this world as Mr. Bacon and I want to leave as Mr. Bacon,” he insisted.

Both men, then, disdained in the other what they pushed away in themselves — class for Bacon, risk for Freud — which made for a volatile and combustible mix. Their falling-out was both inevitable and long on the horizon.

Viewed as “Francis Bacon’s sort of pet” through most of the ’60s, according to London gallery owner Anthony d’Offay, Freud’s style, under the influence of Bacon and Frank Auerbach, began to loosen up in the ’70s, his use of painting growing more visceral, and his reputation surged. It was more than Bacon could take.

“Everything Lucian does is so careful,” sniped the grandee of dismemberment and chaos, wandering around Freud’s big exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1974, whose works he called, “realistic without being real.”

Occasionally sighted together in the ’80s, the two men would squabble and go years without speaking.

“She’s left me after all this time,” Bacon was once heard to complain in the years before his own death in 1992. “And she’s had all these children just to prove she’s not homosexual.”

The ostensible reasons for their falling-out were always silly, but the depth of feeling that underlaid it was not.

When the Tate’s Nicholas Serota approached Freud to loan one of his Bacon paintings, Two Figures in a Bed (1953) for Bacon’s 1985 retrospective, Freud refused, much to Bacon’s annoyance. Considered too risqué to be exhibited in the ’50s, the brutish depiction of two male nudes, “wrestling on a bed,” was considered by Freud to be one of Bacon’s finest paintings. He pawned it many times over the years, getting greater sums for it every time, each time breathing a sigh of relief when he was able to get it back. It hung in a gilt frame over Freud’s bed until the day he died.

The Lives of Lucian of Freud: Fame, 1968–2011 will be published on January 19 by Knopf, and Francis Bacon: Revelations on March 23 by Knopf