In many ways Burr was a thoroughly modern New Yorker, carefully managing his branding from early days at the College of New Jersey, better known today as Princeton University, where his father had been president. There he was a charter member of the nation’s oldest college debate union, the Cliosophic Society. Then (as it still is now), Clio was something of an incubator for next-generation powerbrokers. In Burr, the requisite manners and charisma were honed, but ultimately couldn’t save his fall from grace in the volatile world of partisan politics.

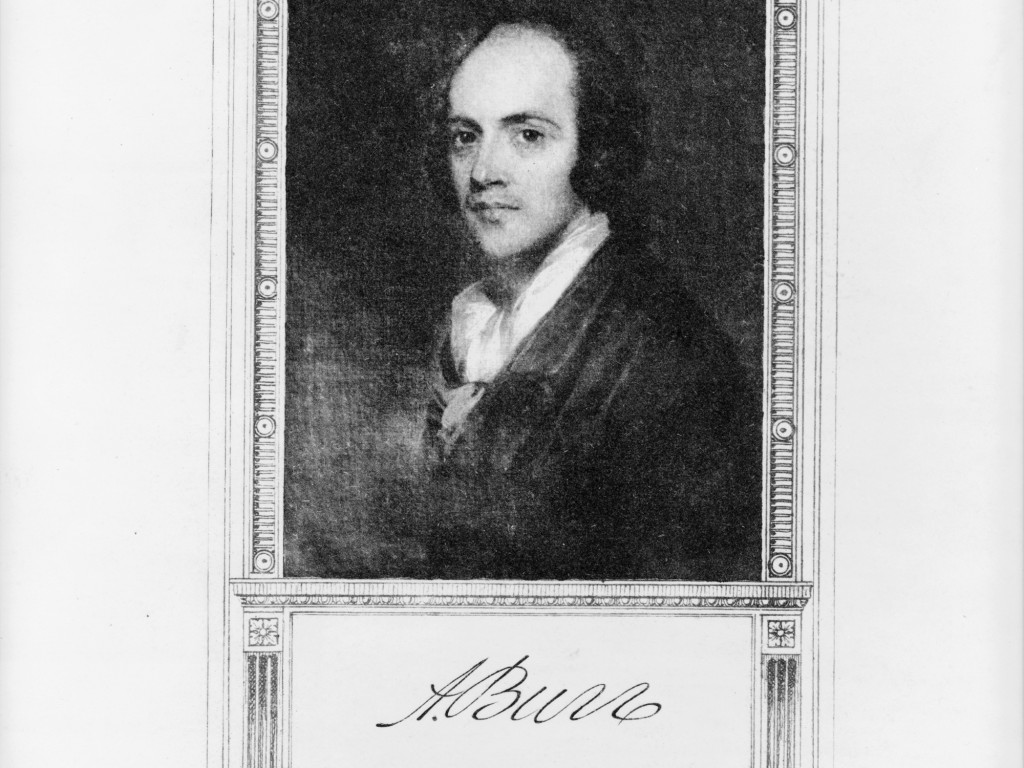

As a man on the make, he was both envied and ridiculed for his intelligent, elegant conversation and easy charm, his enemies mocking his “Chesterfieldian graces”—a sneery reference to a renowned contemporary author of a guide on social etiquette. Burr’s respect for intellectual women was dismissed as mere stagecraft, a grand manipulation. Not considered particularly handsome, neither was he conventional when he married. His choice of a wife was unusual: Theodosia Prevost was older than him, and highly literate.

Burr did shine on a stage, displaying his social finesse at parties—and there were plenty in the course of his ascent, many at the 26-acre estate which is, today, the site of a recent land grab by Google and Disney for their Manhattan headquarters. Tagged “Hudson Square” by enterprising developers, the area once known as Richmond Hill straddles the two trendy neighborhoods of SoHo and the West Village.

The estate house doubled as a headquarters for George Washington during the Revolutionary War, and later when New York City was the nation’s first capital, Richmond Hill served as residence to vice president John Adams. By 1793, Burr, a U.S. senator, occupied the property with his wife and daughter, though his wife would die a year after they settled in.

It’s long gone now, but the house behind high gates and views of the Hudson, was once accessed by a long driveway gracefully winding up to the Ionic-columned entry. In the fashion of the day, there was a picture gallery, a grand dining room, and a hall of mirrors. The library, filled with rare volumes imported from England and Continental Europe, was a gentleman’s prized possession and a mark of status. There were fancy Brussels carpets and a pianoforte. The greatest luxury was a large bathtub, which was something of a novelty then. The rolling property with its straight rows of poplars featured a pond open to the public in winters for ice skating at what is now the corner of Bedford and Downing Streets. The land was first developed in 1760 by British Army paymaster Major Abraham Mortier, and Burr first set eyes on it while reporting here for meetings with Washington as aide-de-camp to General Israel Putnam.

Burr and his wife excelled at the art of conversation, and their 14-year-old daughter (also named Theodosia) quickly became a gifted salonnière like her mother. Father and daughter carried on the tradition at Richmond Hill and entertained European and American intellectuals at parties that were legendary long before the Astors entered the social scene. Among the many guests was Alexander Hamilton. Despite their political rivalry, the two men shared the same circle of friends and acquaintances. Others who trooped through Richmond Hill included the young artist John Vanderlyn whom Burr sponsored, offering him a place to paint and entrée to the city’s elite society. Noted English writer John Davis stayed at Richmond Hill crafting his celebrated travel narrative of the United States. Davis remembered his host as he sat at the breakfast table, book in hand. Knowledgeable in the arts and literature, Burr was, Davis wrote, no less skilled in the “science of graciousness and attraction.” Dismissing the charge of superficiality, Davis observed that Burr, credited for his “urbanity,” never indulged in false familiarity.

Another notable guest was Mohawk chief and orator Joseph Brant, or Thayendanegea. The celebrated negotiator, the most important Native American of his day, was related to Theodosia Burr through marriage. Burr and his wife were also acolytes of the famed English feminist and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. Together, they saw to it that their daughter was (uncharacteristically) schooled in the traditional male curriculum of math, history, Greek, Latin, Italian, and French. The Burrs intended for their daughter to prove that women were the intellectual equals of men; her precociousness was touted by observers and mocked by Burr’s enemies. We forget that feminist ideas were considered ridiculous by most of the leaders of America’s founding generation.

In the popular imagination, Burr has always cut a tantalizing figure to both those who respected and disparaged him. Burr’s legacy has always been wrapped in myth, whether in his newest incarnation as the rapping villain in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, and the admiring historical fiction of Gore Vidal’s Burr in 1973, and as far back as the anonymous author of an 1861 book of Burr erotica. More fiction has shaped how he is remembered than careful historical analysis.

“Burr kept a secret cache of risqué letters, tied in red ribbon, that he instructed his daughter to destroy if he fell in the duel with Alexander Hamilton .”

Though Burr, as a feminist, was one of the first lawyers to specialize in helping women get divorced or claim inheritances, his relationships with women never fit one mold: He had many female friends, and a long list of sexual liaisons. After his wife died in 1794, he kept a secret cache of risqué letters from his paramours, tied in red ribbon, that he instructed his daughter to destroy if he fell in the duel with Alexander Hamilton. His reputation certainly provided fodder for his political foes. One outrageous pamphlet distributed during the election of 1800 claimed that Burr had single-handedly populated the city of New York with hundreds of prostitutes. Adding to his reputation as a “ladies’ man,” at the age of 77, he married the equally scandalous Madame Eliza Jumel, an actress born in a brothel (then mistress, wife, and widow) of a wealthy French wine merchant.

In his professional life, he embraced election reforms and liberal banking policies; his New York welcomed immigrants. A lawyer, politician, urban planner, and innovator in corporate finance, Burr was the mastermind behind the Manhattan Company. The water company-turned-bank was the first institution in the city to lend money to ambitious men of the middling and lower ranks who were not part of the Federalist circle of propertied and mercantile elites. Burr’s design for incorporation was flexible, granting the unique institution the power to expand its services, including selling insurance, which may help explain why its successor, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. thrives today.

If Burr’s Manhattan Company was a success, he managed to lose his manorial estate to John Jacob Astor, who subdivided and sold off storied Richmond Hill after buying out Burr’s debt for $25,000. Astor paid to have the house rolled off the property and down the hill where it became a resort then later the Richmond Hill Theatre. At its zenith it hosted Italian opera, but the former home of two vice presidents eventually lost its luster, becoming a shabby playhouse and, in time, the site of a circus. In 1849, it was torn down.

Burr was both revered and reviled, sought after and hunted down, rising to one of the nation’s highest offices, then retreating to Europe to escape creditors after being cleared of treason charges. He lived and died here 200 years ago, but Burr’s story still resonates and is one that repeats itself to the day, echoing our failings and achievements, and more than anything, our resilience.

A carefully cultivated identity was not the only attribute that qualified Burr as a quintessential modern New Yorker. Despite his ever-controversial legacy, Burr saw himself primarily as a problem-solver and an innovator with an insatiable curiosity. In today’s New York, he’d be working at a startup, or perhaps at Google, just steps from the former Richmond Hill. And he’d understand the pace of the city, too. As one acquaintance aptly remarked, Burr “was always in a hurry.”