It is a late May morning and Amanda Brainerd, an Upper East Side mom, real-estate broker, and soon-to-be-published novelist, is recalling her exuberant youth.

“I was wild, wild. I wanted to do anything possible to have an intense experience. I was like a gigantic sponge.”

For a teenager with a low threshold for boredom and a high capacity for adrenaline, growing up in Manhattan in the revved-up ’80s was nirvana.

“So much of what was fascinating about that decade was what was happening in New York — there was so much creativity in that era, especially in the downtown club scene,” recalls Brainerd, who spent 11th grade frequenting SoHo art galleries and the legendary club AREA. “I wanted to relive that world through my characters.”

Brainerd, 53, is speaking on the phone from the family weekend property in Connecticut, where she is quarantining with her husband, their three children (two of whom are at college, the youngest in high school), and various relations in what sounds like a pastoral idyll. While the parents quarantine in one house, the kids, including her 16-year-old nephew, occupy another.

“They’re playing Swiss Family Robinson treehouse and having an absolute ball. They’re planning meals — they’re all strictly vegetarian. They’re doing their own grocery shopping and most of their own cooking.”

Brainerd goes by their quarters and they’re in the backyard earnestly performing their fitness regimens. “It’s so shocking how wholesome they are,” she says, roaring with laughter.

It is a rather different scenario from the one that inspired her debut novel, Age of Consent — an engrossing page-turner of a story about a closely knit group of friends coming of age in a world of wealth, recreational drugs, and dysfunctional parenting, set among the verdant lawns of a Connecticut boarding school and the art scene and seedy digs of downtown New York.

By her own admission, Age of Consent loosely reflects Brainerd’s background (although she stresses she avoided drugs). For starters, both Brainerd and her main protagonist, Eve, are the daughters of successful New York financiers and stay-at-home mothers (in the author’s case, the hedge fund manager Oscar Schafer and his wife, Diane). Both grew up on the Upper East Side, and were expelled from boarding school in their sophomore year for sneaking off campus to see a rock band.

“It was U2 and it was an amazing concert in a very tiny venue. I’d [gone] not thinking that some twentysomething teachers would be at the concert. To me they were old people!” Brainerd recalls of her abrupt departure from Choate. “So I got busted and got expelled two weeks before the end of the semester and came crawling back to Nightingale-Bamford under a cloud of shame.”

Like the author, Eve is also book smart and artistic, and struggles to forge her own path under the yolk of authoritarian parents. (“My parents were very strict and really never let me do anything; I’m still bitter about it actually.”) And both are left contemplating the effect of damaged and absentee parents on their circle of friends.

“Writing this novel was a way of parsing through feelings that I had covered up or put away for many years about being a teenager,” says Brainerd, who has an ear for teenage dialogue. “And it was a way for me to explore my bewilderment at some of the ways that friends of mine were neglected by their parents.”

In Age of Consent, the teenagers hook up, take drugs, navigate tribal cruelties, and slip into coercive sexual relationships with older men, the soundtrack of the ’80s humming in the background. The adult figures, none of them laudable, linger on the mar-gins of the page, casting shadows.

Brainerd’s boarding school mishap didn’t push her off track for long — after Nightingale she went to Harvard and then Columbia, where she earned a master’s degree in architecture, before working briefly for Christopher Buckley and then as an architect, later settling into a successful career in real estate. She says the idea for the book came during one of the dinner parties that she and her husband, the architect Charles Brainerd, often give at their Upper East Side apartment.

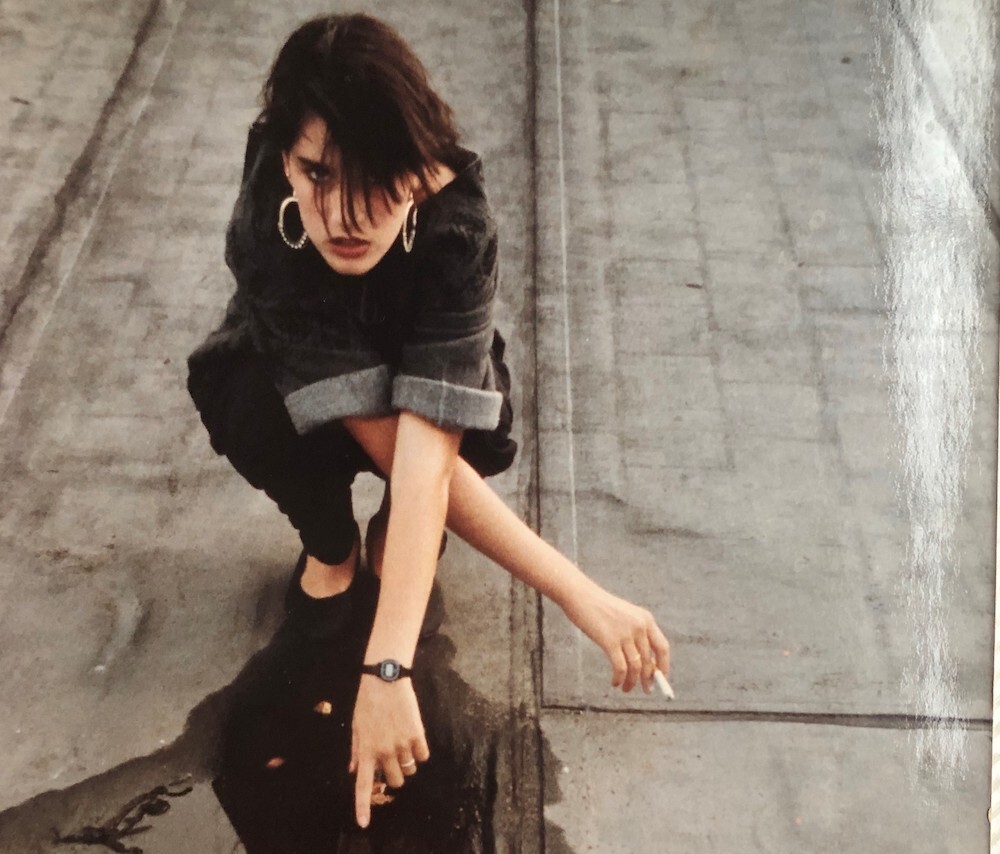

Photo by Theo & Juliet“I was talking with an old friend about what it was like to be a parent now in New York versus what it was like to grow up in the city and what parents were like in the ’80s… We said, do you remember those brothers?” she recalls, referring to siblings who were rumored to live with little parental oversight in an apartment on Fifth Avenue.

“You can imagine nothing good happened… We were saying, can you believe the things people did?” She pauses. “One of the reasons there’s so much helicopter parenting is that we ourselves felt so neglected in so many ways, parents were just totally checked out.”

Brainerd initially contacted six people — although by the end of her research she had spoken to 30 — and began to interview them with the intention of writing an oral history.

“This is a work of fiction, let’s be completely clear. But while I was gathering these stories, I quickly realized it had to be a novel, mostly because I wanted to not necessarily tell exactly what had happened. And in some cases what actually happened was so shocking that it was not believable. I had to tone it down to make it palatable.”

How did her friends who were neglected turn out?

“Most of them are pretty screwed-up, unfortunately. I don’t think you can put the toothpaste back in the tube, you cannot fill the void,” she observes. “They carry this empty place around in them forever and there’s nothing that can fill it.”

But with Age of Consent, she says, she wanted to leave open the question of blame.

“Listen, there’s no manual, [parenting] really is a hard job. I’m not trying to be judgmental, I’m really not. I just wanted to understand.”

In Connecticut, Brainerd is working on a second novel and feeling lucky that her children have turned out the way they have.

“All throughout my 20s and 30s, before I started having children, my mother said, ‘You’ll see. You’ll have your own Amanda, you will see what I suffered,’’ she laughs. “And actually, it hasn’t happened. None of our children have given us a run for our money the way that I did. It’s miraculous.”