As far as indicators go, the heart health of a city’s denizens seems inversely proportional to its economic vitality. The better off a city is doing, the more clogged its arteries. So what better measure of New York City’s renaissance than revisiting its steakhouses?

The steakhouse: locus of wheeling, focus of dealing, where bottles of Bordeaux flow and slabs of steer sit on vast plates of snowy porcelain. Over the last year, as hurly-burly Midtown slumbered under Covid ash like Pompeii, the steakhouse business slowed to molasses. But then vaccines came, masks receded, indoor dining surged, and expense accounts demanded draining once again. ’Twas the season for the steakhouse to awaken. So, I visited three of the best: one new, one old, and one so old it’s due again for a check-up.

Remember when the Fulton Fish Market, under the FDR, smelled like fish and the Far East Side and felt Mad Max apocalyptic? Remember when Pier 17 was the suburban mall, with Banana Republic and touristic tchotchke shops that suburban kids would visit on field trips to the city? I sure do. I was that suburban kid. Those memories are just snippets of an old song skipped past while scanning the airwaves for today’s summer bangers.

There’s little trace of that world as I roll up to the sparkling South Street Seaport, built after Hurricane Sandy by the Howard Hughes Corporation and which aims to be what the Hudson Yards was supposed to be on the West Side, fifty blocks uptown. It’s all glimmer, glass, and good food. There’s a Momofuku Ssäm Bar, a Jean-Georges Vongerichten patio affair called Fulton, and a just-opened steakhouse by Andrew Carmellini called Carne Mare.

Photo courtesy of Carne MareAnyone who knows Carmellini or his work — Locanda Verde, Lafayette, the Dutch, and more — knows the Buckeye-born, Boulud-trained chef is nothing if not a canny restaurant whisperer. He knows the exact ratio of familiarity to experimentation to make every meal both comforting and exciting. A steakhouse, never really a site for innovation but not begrudging it, is his meat and potatoes. The two-story steakhouse — designed by Martin Brudnizki, whose clubby aesthetic has taken over posh spots from Miami and London — is like a gigantic captain’s cabin: wood-paneled walls, butterscotch-leather banquettes, and views of the harbor and the tall ships bobbing nearby. Carmellini calls the place an Italian chophouse, but it has all the features of a steakhouse: a focused menu with seafood up top, meat at its center, contorni — or sides — dwelling in the lower fourth, and decadence glitter-bombed throughout.

On a recent Friday night, waiters wore throw-back maroon suits and strode amongst the 250 seats with purpose. Though concise, the menu, when it arrives, is as big as a sail. If the Italian sirocco blows through the open kitchen, it does so gently and often with a whiff of the sea. The octopus carpaccio — which looks like delicious terrazzo — is sprinkled with pickled peppers and crispy pepperoni cups. It sounds like a tongue-twister, and it tastes like a roller coaster of taste and texture. A pair of mozzarella sticks is festooned with quenelles of ossetra caviar. (Conceptually sound, alas, the cheese sticks overpower the caviar, a rare misstep.)

Photo courtesy of Carne MareElsewhere caviar is put to much better use, as in the case with hand-cut fettuccine, in which the admirably firm noodles tangle through countless bursting burrs of salmon and sturgeon eggs. But the pièces de résistance are naturally the meat. While other steakhouses often reserve the place of honor for a porterhouse or a tomahawk — both of which are present here — Carne Mare’s masterpiece is a 16-ounce prime rib rubbed with porchetta-style spice and slow-cooked.

It arrives, rosy as a ship’s port lantern, and so big it practically begs for a foghorn to announce its arrival. But O Captain! My Captain!, the tender joy of a ruddy steak, ringed in rosemary, sage, and fennel, knows no bounds. I stumble through the tables now, meat-full and Manhattans-drunk, for a breath of fresh air.

Had I a telescope, from the patio I might have been able to sight another of the city’s great steakhouses: Gage & Tollner, an almost 150-year-old steakhouse brought back to life a few months ago by a trio of talented restaurateurs. Whereas most steakhouses fortified themselves with endless lobbies and antechambers to keep the public at bay, Gage & Tollner opens right onto the bustle of Brooklyn’s Fulton Street.

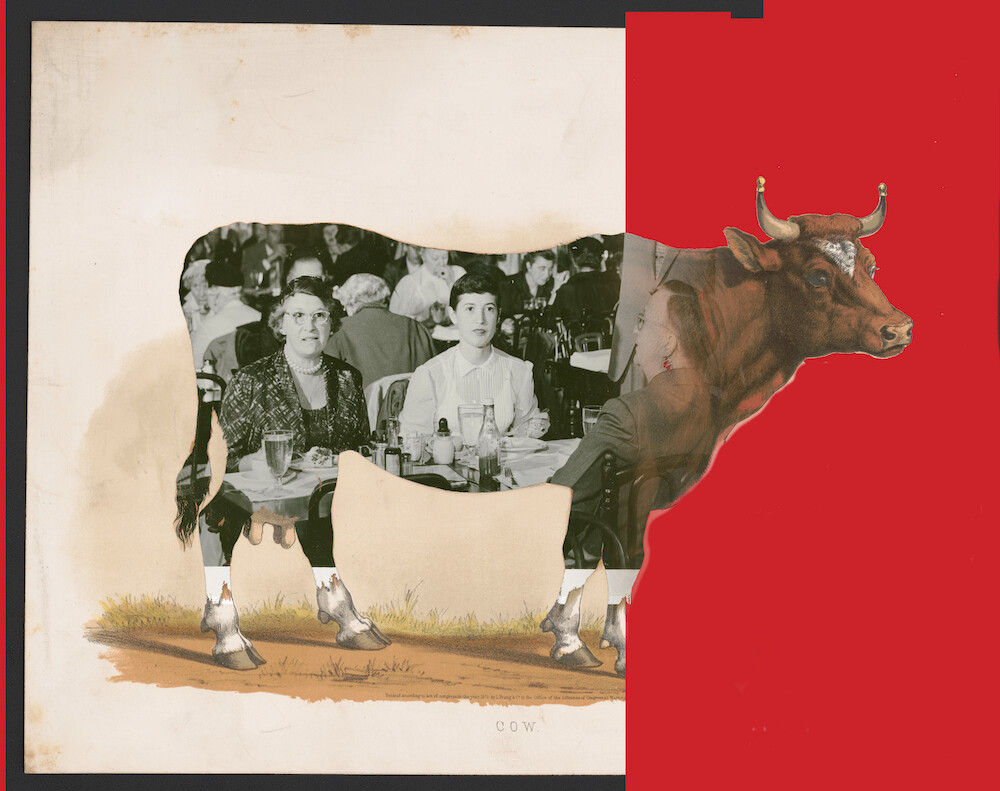

Gage & Tollner’s history is as rich as American wagyu. When it opened in 1879, there was a Gage (Charles) and a Tollner (Eugene). Then the restaurant was buffeted by fortune and changed hands more often than a poker player. Gage and Tollner were replaced by Cunningham and Ingalls, then Brad Dewey, whose son, Ed, sold it to Peter Aschkenasy in 1988, who sold it to Joe DeChirico in 1995, and thus the restaurant endured well into the 21st century. It closed in 2004 before its current rebirth under the care of chef Sohui Kim and her partners, St. John Frizzel and Ben Schneider.

Photo via the Brooklyn Historical SocietyWhat makes the current incarnation so vital is that it draws not simply from the days of Charles and Eugene but also from the reign of chef Edna Lewis, already the grand dame of Southern cuisine when hired in 1988 (at age 72!) to run the kitchen. Her preparations tilted Southernly, including a she-crab soup, fried chicken, and a coconut layer cake. In Sohui Kim’s hands, Lewis’s creations are modernized and, slightly, Koreanified. Kim adds a pinch of minced kimchi to the bacon atop clams casino, redubbing them Clams Kimsino. The crisp fried chicken, far from the gochujang variants found in K-town though no less tasty, is accompanied by a tart kale-and-kimchi slaw. But there are plenty of classics too. The devils on horseback seemed to gallop into my mouth of their own volition. Never have dates wrapped in bacon moved so quickly. That she-crab soup, bursting with crab roe, recalled the glory of Gage’s golden years to an herbaceous T. And the coconut cake, though given a modern spin and a layer of edible flowers by pastry chef Caroline Schiff, is as sweet as the original.

Photo by Lizzie Munro, courtesy of Gage & TollnerThe riskiest move, in my opinion, are the steaks themselves. For all the hullabaloo over farm-to-table cuisine, grass-fed beef remains a rarity in steakhouses. The reason is simple: a grass-fed steak is a temperamental protein, which turns tough fast, and tastes — gasp — like an actual animal. (I remember the shock of grass-fed beef at M. Wells’s steakhouse when it opened in 2014.) Nevertheless, here the flavors are pronounced by the 28-day dry-aging, the richness enhanced with butter basting and the char as thick as the black night.

Back in Manhattan, the view is much different from the corner table, the so-called Owner’s Table and the choice seat at Michael Lomonaco’s 15-year-old classic Porter House. Central Park is a silent green carpet below; Christopher Columbus, in the middle of the circle on his column, is at eye level.

One doesn’t go to Porter House to nibble. One goes to indulge. Perhaps, in that way, the corpulent Fernando Botero sculptures at the foot of the escalators aren’t so much guardians as harbingers. Porter House is as removed from the street as Gage & Tollner is close; up on the fourth floor of the Columbus Center, it has reached empyreal heights for a restaurant. (It shares the floor with Per Se and Bar Masa.) Perhaps that’s where chef Michael Lomonaco, the longtime chef of Windows on the World, feels most comfortable. But the fare here is grounded.

Photo by Noah Fecks, courtesy of Porter HouseOf the three steakhouses I visited, this one is the least changed. Simply the classics done exceedingly well. There can be no quibbling with the four U8 shrimp that arrive, as if a quartet of spooning friends, to be dipped into vodka-tinged cocktail sauce. Nor is there truck to be had with the four thick tranches of bacon, smoky and sweet, on its own plate as an appetizer. (Together, the shrimp and bacon dishes must make the least kosher table in the entire Upper West Side.) Like at Carne Mare, the menu is quite spare. Of pastas there are three, the best being a truffle-and-morel-laden risotto that tastes of springtime. But the meat is paramount.

For my taste, the best cut is the bone-in strip loin. Neither the largest nor showiest of steaks on the menu, it is nevertheless the most flavorful, especially when accompanied by a small gravy boat of cognac au poivre sauce. A half hour into the meal, the table looks like a Lucullan Busby Berekley production, the steak now surrounded by a seafood platte in its geometric beauty; gigantic onion rings; a festival of spring greens; slices of fresh and buttered sourdough — Why fill up on bread? you ask, as if I am an iron-willed god and not a mere mortal — and a martini glass with a Manhattan in it. Meanwhile, just out the window, Manhattan is aflame with the setting sun. The city looks beautiful from this perch: vibrant, and, if one judges from its steakhouses, if not exactly healthy, then joyously decadent.