After falling from a waterspout, onto which he had clambered from a moving train while filming his 1924 silent comedy Sherlock Jr. Buster Keaton complained of a headache. He treated it with whiskey until a few days later, when an X-ray revealed he had broken his neck — just one on a long list of shattered bones, fractures, and concussions sustained in the course of a nearly 50-year career, as recounted in James Curtis’s authoritative new biography of the filmmaker. “We knew from bitter experience in the old days that stuntmen don’t get you laughs,” said the comedian, who emerges from the pages of Curtis’s Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life not just as the first indie auteur but as the direct forerunner of Indiana Jones and Jason Bourne: the first action hero.

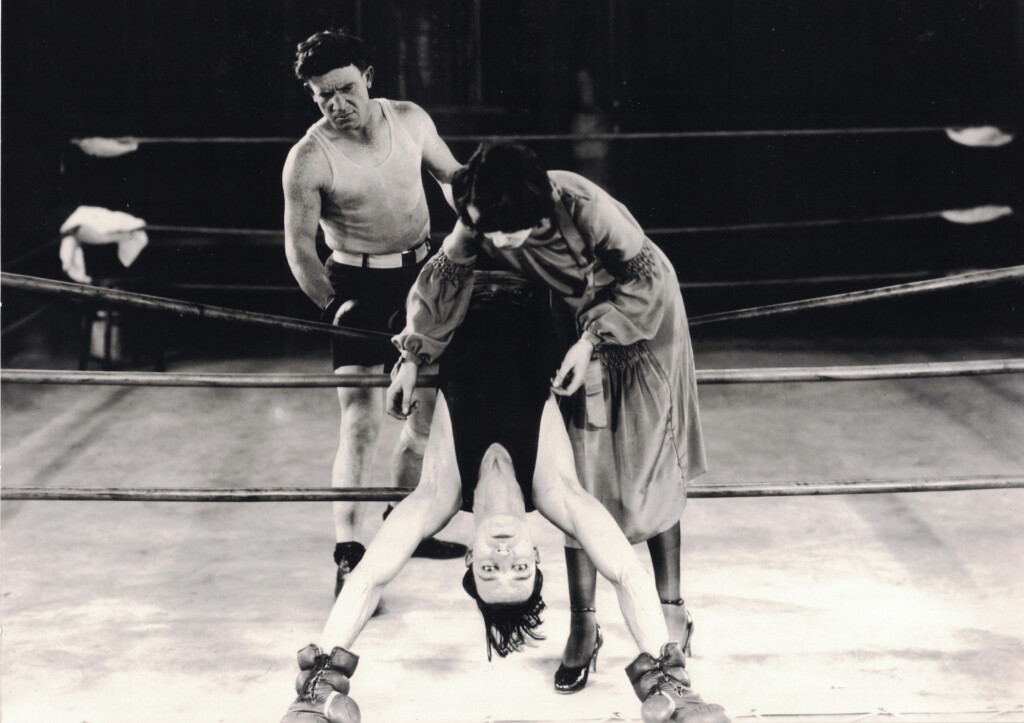

Welterweight champion Mickey Walker called Keaton’s climactic fight scene in Battling Butler (1926) “the greatest battle I ever saw outside of the ring.” In College (1927), Keaton pelts his adversary with whatever he has at hand — cups, dishes, books, a bust — just like Matt Damon’s Bourne. “The best way to get a laugh is to create a genuine thrill and then relieve the tension with comedy,” said Keaton, whose films are the original recipe for the action-plus-comedy formula of today’s billion-dollar franchise industry. Spielberg pastiches Keaton all the time. When Indiana Jones is punched through his windscreen in Raiders of the Lost Ark, disappears under the wheels of his own truck, attaches his whip to its undercarriage, and hauls himself back on board to resume his fight with a Nazi, the beautiful, Rube Goldberg–ish circularity of the gag echoes the climax in Spite Marriage (1929), in which Keaton is thrown from the bow of a yacht, gets dragged under by the current, clambers aboard a small yawl being dragged from the stern by a rope, hauls himself in, and rejoins the fight.

Photo by John Springer Collection/Corbis, via Getty Images“I was just a harebrained kid that was raised backstage,” said Keaton, who as a child was part of a vaudeville act with his parents. Billed as “The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged,” he had a suitcase handle fitted onto the back of his costume so that his father, Joe, could hurl him across the stage like a human bowling ball, sometimes as far as 30 feet. His father was a drinker. “When I smelled whiskey across the stage I got braced,” Keaton said. By today’s standards, it borders on child abuse. They spent half their time dodging the officers of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children; in order to deter their investigations Joe once took Buster to the New York City mayor and asked him to strip bare in front of him to show he had no bruises, but he had long since learned to avoid taking the fall on the back of his head, base of his spine, elbows, or knees. As Kenneth Tynan noted, Keaton’s philosophy was that of the stoic: you fall hard, you get right back up. When he cracked a smile, the audience didn’t laugh as hard. “If something tickled me and I started to grin, the old man would hiss ‘Face, Face!’ That meant freeze the puss.”

Photo by Bettmann/Getty ImagesIn his 1949 essay “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” James Agee wrote that “Keaton’s face ranked almost with Lincoln’s as an early American archetype, haunting, handsome, almost beautiful, yet it was also irreducibly funny.” At the age of 21, after 16 years of kicks, jumps, tumbles and falls, he broke up the act and teamed up with actor and comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, with whom he honed the art of the sight gag to the point of balletic abstraction. Casually striking a match from a passing train in Out West (1918), Arbuckle also strikes a note of pure cinema. Keaton “lived in the camera,” said Arbuckle. Carrying the entire film around in his head allowed him to improvise on the spot, using what he called “the huddle system”: “We all get our heads together like a bunch of college-boys taking football signals. Then we figure out what comes next.” He buddied up easily. With his female costars he was fond, fraternal. “Buster was very sexy, very relaxed and easy with women,” said the silent movie star and Jazz Age icon Louise Brooks. “Of all the movies I made, I liked best working for Buster Keaton,” said actress Virginia Zanuck.

Photo by John Springer Collection/Corbis via Getty ImagesHis home life was a rockier climb — three marriages, the first to actress Natalie Talmadge in 1920 in one of Hollywood’s most celebrated weddings, ending in a nasty divorce that lost him his children and mansion. Keaton took to camping out in his latest purchase: a luxury cruiser land yacht. Sound had arrived, and Keaton’s baritone voice was “very much like that of Dante’s Satan — sepulchral, low, baleful and unmelodious,” noted Hollywood Filmograph. Lacking the business acumen of Chaplin and Lloyd, who had full ownership of their productions, Keaton’s run of great movies in the silent era were all made independently with the backing of mogul Joe Schenck, his brother-in-law, who had also married a Talmadge girl, and the films were expensive. Schenck was outraged that Buster spent $25,000 to buy the ship used in The Navigator, for which he shot 1,000 feet of underwater action, including a gag in which he directs traffic for a school of fish that cost $10,000 to rig up and shoot.

“There I was, on top of the world — on a toboggan,” said Keaton of the tail-end of the 1920s, sensing even in his downfall the hint of a sight gag. Several of his films feature in Sight and Sound’s critics list of all-time best movies, and are now part of the National Film registry, but 1926’s The General was a flop — it was too perfect, said film critic Pauline Kael — and when Schenck bailed on Keaton’s indie productions and MGM came knocking, the comedian caved.

Photo courtesy of Cohen Media“In the end I gave in,” he said. He was miserable at MGM, boxed in by writers — he counted 22 on one production — and creatively henpecked by Irving Thalberg. “You had to requisition a toothpick in triplicate,” complained Keaton, who struggled to find his rhythm in the sped-up clockwork of drawing-room farces. “Keaton’s comedy, for all its demented logic, was more sober and contemplative, less frenzied,” writes Curtis in his biography, perceptively. His first pictures, the two-reel shorts, unfurl with the logic of dreams. There is a sleepwalker’s stillness to his face, as he scrambles to avert catastrophe. Six of his films turn out to be dreams, most famously Sherlock Jr., about a projectionist who dreams himself into a movie-within-a-movie.

Keaton’s is the old story: the daydreamer who got chewed up by the studios. Pretty soon he had followed his father into booze, turning up for work drunk, earning telegrammed reprimands from Louis B. Mayer, and eventually getting fired by MGM in 1933. Keaton retired to the San Fernando Valley, raised chickens, and made the occasional appearance in television commercials, teenage beach-party movies, Chaplin’s Limelight, Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, and 1964’s Film, from an original screenplay by Samuel Beckett — an intriguing collaboration, for his tools included what Orson Welles called “the comedy of futility,” just like Beckett. In Hard Luck (1921) he played a man whose various suicide attempts — stepping out into traffic, lying in front of a train, drinking poison — all fail, leaving him with no option but to join an expedition to capture an armadillo. That was Keaton: capturing our sympathy without asking for it, the quiet eye of the storm, demonstrating grace under pressure, a master of the frozen puss.

Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life by James Curtis is published by Knopf on February 15.