Photo by Getty ImagesThe advent of Prohibition in 1920 may have curbed the sale of alcohol, but it did nothing to stanch the flow of liquor at the parties thrown by Condé Nast. Overnight, as in all big cities, a thriving black market was born, and Nast was among its most robust patrons. Just how he managed to have free-flowing French Champagne was due to the ingenuity of his secretaries—Mary Campbell and Estelle Moore. According to Diana Vreeland, who attended these fashionable parties long before becoming the editor of Vogue, Nast knew that “Prohibition was a time when there tended to be a lot of excitement. It was because you weren’t allowed to drink that you drank anything you could get your hands on. People would go into the bathroom and drink Listerine! Anything that might have a crrrumb of alcohol.”

Photo by Getty ImagesNast’s secretaries were the magicians behind these first parties. It was they who summoned the caterers, planned the menus, ordered the flowers, hired the musicians, and somehow found all the liquor (more than likely through some network at New York’s docks). They also maintained the much-talked-about A, B, and C lists tracking aristocrats, entertainers, musicians, artists, and business titans, ensuring that just the right cocktail of people attended the correct party.

Photo by Getty ImagesProhibition only added to the excitement of Nast’s guests. The invitees had to give a password before they could even ascend the elevator. Revelers found their Champagne chilling in a bathtub, as readily available as the scotch, rye, gin, rum, vermouth, brandy, and sherry. Menus received the same scrutiny. Such opulence, such care to detail, reflected Nast’s perfectionism, if not an actual love of crowded rooms. As his larger parties warmed up, and when Nast was satisfied the scene was perfectly set, he could often be found in a peaceful corner of his library, reading or playing a quiet game of bridge with other like-minded friends.

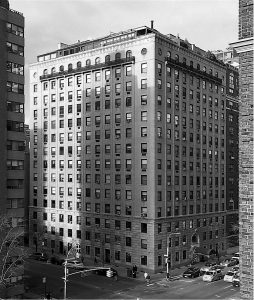

Even as the parties initially got under way in 1922 at Nast’s 470 Park Avenue home, their ultimate stage was being readied at 1040 Park Avenue: Nast had bought a 30-room penthouse duplex while it was still in the blueprint stage and, after having it transformed to meet his exacting specifications, he eagerly awaited its debut.

Nast’s invitees had to give a password before they could even ascend the elevator.

With interiors designed by none other than Elsie de Wolfe, Nast’s elaborate nest had its unveiling on Sunday, January 18, 1925, shortly after he moved in. The legendary interior decorator had a flair for all things French, so no New York apartment could have been decorated with more richesse.

The sprawling residence unfurled itself atop a building designed by sought-after architects Delano & Aldrich, and had been modified to Nast’s requirements. Throughout the previous year, he had the team rework the space to include ten entertaining rooms on the roof, with suites of domestics’ rooms and sleeping quarters neatly separated from the rooftop paradise with a strategically placed staircase. In the days before air-conditioning, Nast had to rely on crosstown breezes to keep his guests cool in the summer months; a conservatory, or solarium, was added a few years later.

Photos by Getty ImagesSince Elsie’s spiritual home was the Villa Trianon at Versailles, she decided that un style à la française would reflect both Nast’s heritage and the elegance of his magazines. The Louis XV furniture was upholstered in a pale sage-green damask. Savonnerie rugs graced parquet floors laid by French workmen brought over for the job. The pièce de résistance was rare 18th-century Qianlong wallpaper that once hung at the baronial stately home Beaudesert in England. Once the conservatory was enclosed, guests were able to admire the view from their tables, or wave to playwright and theater director Moss Hart in a Park Avenue apartment across the way.

It was here at 1040 that Nast assumed the title of New York’s most consummate host—and he did so alongside Frank Crowninshield, editor-in-chief of Vanity Fair: a wit, connoisseur of arts and letters, and urbane proponent of gracious living who had known Nast since his early years in New York. “Crownie,” as he was known, moved in with Nast and helped preside over the endless parade of parties. Both men observed the torpor of the Gilded Age being painted over by newcomers of a different pedigree. Their response was to hitch high society to the hot engine of emergent café society, the parties becoming an effortless (and effervescent) blend of the new and the old.

Photo by Getty ImagesNast would mentally catalogue the most amusing and sociable people from Europe and America, invite them, and then note who showed, and how long they stayed. Of course he was already factoring in the next party in a few weeks’ time—and precisely who deserved to be there again.

That first housewarming dinner-dance included a broad cross-section of guests, among them dancing siblings Fred and Adele Astaire; composer George Gershwin; songwriter-dramatist Arthur Hammerstein; owner of the Algonquin Hotel and host to the Round-Tablers, Frank Case; actress Katharine Cornell; author, engineer, inventor, cartoonist, and sculptor Rube Goldberg; and Vogue and Vanity Fair in-housers Edward Steichen, George Jean Nathan, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Carmel Snow, and Edna Woolman Chase.

Conde and Crownie hitched high society to the hot engine of emergent café society, the parties becoming an effortless (and effervescent) blend of the new and the old.

It was the first of Nast’s bimonthly blowouts at 1040, and it was unforgettable. The guests were carefully selected from those A, B, and C lists: the A-list, carefully curated names from society; on the B, people in the arts. The C was a catchall for every manner of contemporary celebrity—all broken down further into married couples and the unattached. These were meticulously calibrated, and there were of course post-mortem memos that made note of the number of invitations, percentage of acceptances from each list, and how many days’ notice had been given. All associated costs were detailed down to the last waiter’s tip.

On the day of the party, Nast would dress and then make the rounds, checking on the caterers and flower arrangements. After ensuring that every table in his Chinese Chippendale-furnished ballroom had full, round cases of unfiltered cigarettes, he would pivot to the orchestra leader, confirming he knew to strike up the band just as the first guest arrived. Nast discussed the drinks with the barman (including, presumably, which of the home’s dozen bathtubs would be on double-duty for chilling Champagne, spirits, and wines.) Only then could he relax.

On June 13, 1927, following his solo flight across the Atlantic in his plane Spirit of St. Louis, Charles Lindbergh received the warmest of welcomes in New York City, with thousands of admirers cheering his motorcade as it edged up Broadway. Of course, Nast would throw a party for the handsome hero as well. Getting “Lindy” was considered a huge coup, but Nast ended up aghast when he saw his typically sophisticated party guests clawing at the shy aviator and giggling hysterically when they managed to touch him. Nast’s daughter Natica sprang into action, spiriting Lindbergh away to Nast’s bedroom. Only those who could be trusted to behave—and were smart enough to bring more bottles of Champagne and glasses—were allowed entry. So ensconced, the party’s most nonchalant guests (feigned or otherwise) barricaded the door and partied on respectfully.

It got around, about Nast’s Lindbergh party, which only helped to further burnish the reputation of his magazines, and the host himself. Perhaps the most famous guest of all to join in was the iconic Josephine Baker. Crownie and Nast had already managed to introduce the controversial Picasso to America—“that dyed-in-the-Spanish-wool Communist” as he was being called—so why not also invite into their home (and magazine) the polarizing dancer and jazz singer now wowing French audiences with her topless banana-skirt performances? This was the era where, if you wanted to hear jazz, you went up to Harlem. So, naturally, Nast threw a riotous party in Baker’s honor at his home in 1927 and New York’s crema di eleganza didn’t dream of missing it.

“Now that was historic,” wrote Diana Vreeland of the party to end all parties, recalling the legendary performer making her entrance. “Her hair had been done by Antoine, the famous hairdresser of Paris, like a Greek kouros—these small, flat curls against her skull—and she was wearing a white Vionnet dress, cut on the bias with four points, like a handkerchief. It had no opening, no closing—you just put it over your head and it came to you and moved with the ease and fluidity of the body.” Feeling thrilled to have been asked to Nast’s party at all—let alone to one with such a revelation as the guest of honor—Vreeland, at the time a new mother with her own storied career in magazines a decade still in the future, declared: “There was no living with me for days.”

From Condé Nast by Susan Ronald. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.