As a person of notoriety, you have a leg up on other writers, as far as selling books is concerned,” says Ethan Hawke via Zoom from his office in Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill, talking about his third novel, A Bright Ray of Darkness, with disarming candor.

He knows that as a celebrity-turned-author the cries of “dilettante” are all but assured. Moreover, the book concerns a thirty-two-year-old actor named William Harding who, after being vilified by the tabloids for cheating on his wife, checks himself into a no-star hotel and rallies his spirits with a performance as Hotspur in Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Sound familiar?

But before you can say, “Hey, doesn’t that sound like that Ethan Hawke fella?” both book and author have beaten you to the punch. Hawke’s spell in the tabloid inferno is what gives the book its heat.

“Everything in the book is about understanding that sometimes you have to play the role of the bad guy,” says Hawke, 50. “We all want to be good, especially actors. You usually go into acting because some part of you wants to relate to the audience and be accepted by them. If you don’t allow yourself to have a shadow self, you’re out of balance. So understanding the shadow self is a big part of the novel.”

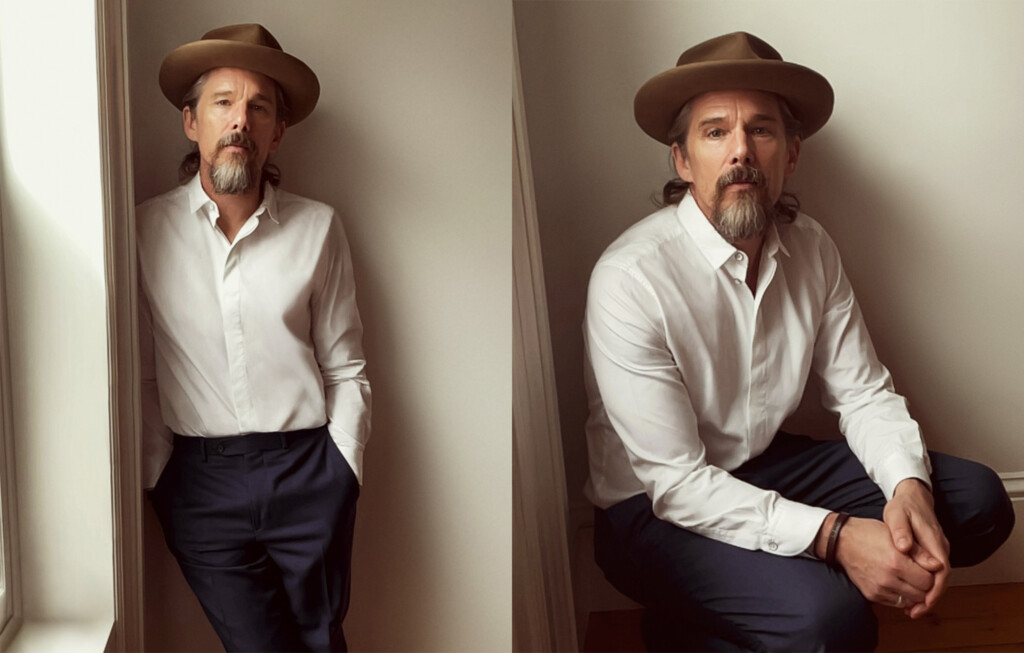

Hawke’s shadow self has had something of a renaissance of late, in Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, playing an eco-radical priest, and Showtime’s seven-part The Good Lord Bird, where he played abolitionist John Brown with gnarled, fulminous intensity.

Since Hawke became the face of Gen X at 23, his gaunt features have acquired a few crags and creases, his trade-mark goatee now longer and tufted with white, adding a seasoning of wisdom to his long, soulful riffs on the importance of keeping the faith and your personal flame intact.

Hawke has always been a great persuader (remember him talking Julie Delpy into getting off the train with him in Before Sunrise?), and in A Bright Ray of Darkness, he lends his skills of exhortation to an array of sharply drawn secondary characters — the play’s director; one of William’s costars; a coke-snorting movie star buddy; his mother — all of whom deliver a series of come-to-Jesus pep talks to rally William’s spirits as he drags himself to rehearsals bleary-eyed from the coke binges and hookups of the night before. It’s a book of sinners and inspirational riffs, a great gift for a friend who’s just had their world turned upside down.

“In a lot of ways, the other characters are ‘me now’ talking to ‘me then,’” says Hawke, who first hit upon the idea for the book after a dinner with his German publisher in 2002. The reviews of his second novel, Ash Wednesday, were good, but they often called his hero the ‘Ethan Hawke character,’ even though he had pushed himself to write about a soldier facing fatherhood, and then split the book’s point of view with said protagonist’s girlfriend, he complained to his publisher.

“They still thought I was writing about [his now former wife] Uma Thurman. People were just picking this book up because I was in Reality Bites.”

His publisher, an éminence grise of the German literary world who had published Gabriel García Márquez and knew Kurt Vonnegut, responded, “Well, do something with it. Let them pick it up for that reason. Give them the meal they think they want, just make it better. It would take Don DeLillo 20 years of research to write what you already know about acting.” The advice hit Hawke right between the eyes.

“I thought, what if I gave myself permission to write about an actor?” he says. “My joke to myself was I can do for the actor what Melville did for the whaler — a great novel about acting.”

That there aren’t that many even good novels about stage actors — Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900), James Baldwin’s Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), and Philip Roth’s The Humbling (2009) come to mind — is perhaps surprising. The thrill of performance and the freedom offered by masks are resonant themes even for nonactors, although the fabric of our lives doesn’t gather itself into transformative tests of mind, body, and spirit every day of the week. (Only on the F train at weekends.)

Hawke’s marriage to Uma Thurman disintegrated in 2003 amid reports of his affair with a Canadian model (not, as it has been sometimes misreported, with the couple’s nanny, Ryan Shawhughes, whom he would later marry.) After the divorce, he holed up in the post-punk rot of the Chelsea Hotel and returned to the theater, playing a sleazy actor in Hurlyburly, and — yes — Hotspur in a production of Henry IV, pouring all his anger into the role of Shakespeare’s vainglorious knight.

Some of the black electricity from that time also found its way into the final installment of Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy, Before Midnight. The book gnawed at him over the years, on planes or in hotel rooms; reading James McBride’s 2013 National Book Award–winning novel The Good Lord Bird, he felt so “jealous that somebody had written something so beautiful and wise” that, after filming completed on his adaptation, he felt galvanized to start work again on his own book, although he still isn’t sure he wants his kids — Maya (22) and Levon (19) from his marriage to Thurman, Clementine (12) and Indiana (9) from his marriage to Ryan — to read it.

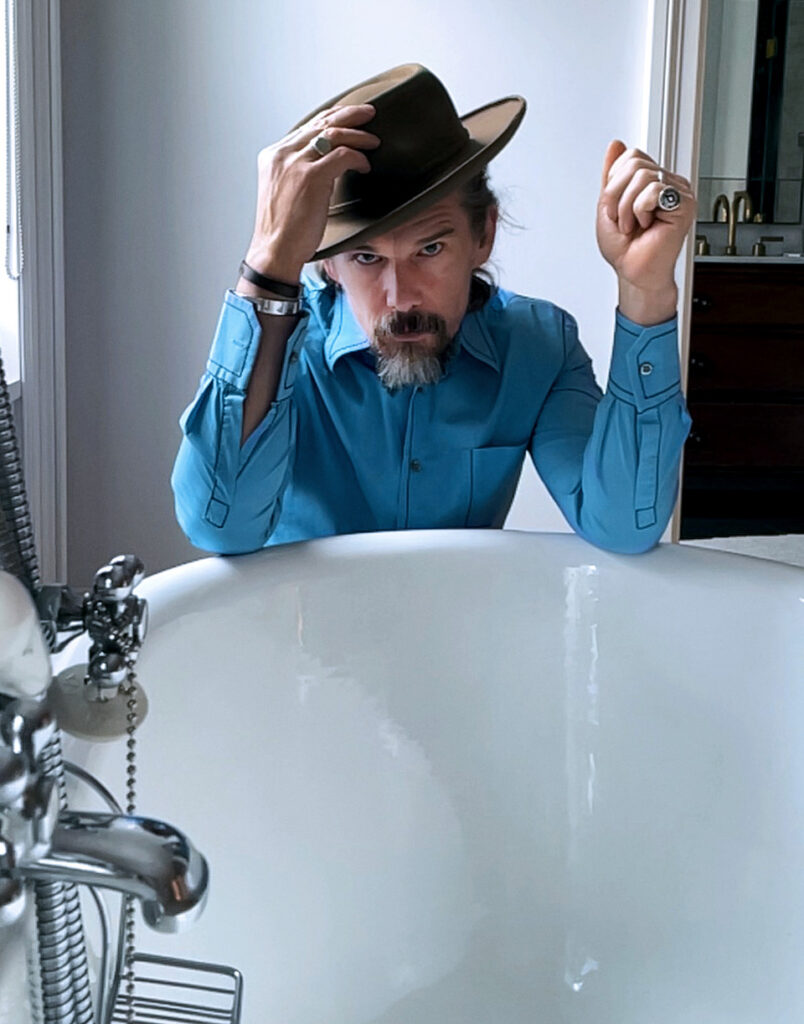

“The dad in me wonders if I should publish it at all. It’s like, if my father was a painter and he felt he needed to paint really personal pictures of himself naked or something like that, I respect his right to do that, but I’m not sure I would want to hang one on my wall — you know what I mean? This one is so personal to me, and I harbor secret hope that other people will enjoy it and that it has value in the world, but it does deal with sexuality and drugs, and a lot of my personal wounds that I don’t feel are relevant to my role as a dad… It’s strange how memory works, isn’t it? That sometimes you look back fondly on the most hurtful times of your life because you felt alive, you felt like you were growing. It’s mysterious to me how I can romanticize some of the most painful parts of my life. I think it’s how we heal. I was really turned-on taking Shakespeare on, too. When you think of acting, that’s what you think of, Shakespeare. And so I wanted to kind of kiss that on the mouth.”

Hawke can’t wait for theaters to reopen and school to return full-time. He’s been home-schooling his youngest at the home he shares with Ryan in Boerum Hill, but wonders what gaps they’re going to have in their education.

“I’m burned out,” he says. “But in a minute, I’m going to go home and have lunch with my kids, and that part I really like. Most days we have breakfast, lunch, and dinner together — for a year. I’m usually home for six weeks, gone for six, gone for three, gone for a weekend… this has been a wild year for me.”

With Hawke’s performance in The Good Lord Bird picking up a Golden Globe nomination, there seems to be light at the end of the tunnel. If some young indie filmmaker were to adapt A Bright Ray of Darkness for the screen, what advice would he give the actor playing the Ethan Hawke role? Too late, I realize I should have said “William Harding,” but Hawke doesn’t seem to mind.

“I was thinking about that word ‘grace’ a lot recently and about what its definition is. And to me, its definition is the ability to accept change, to accept things as they are. And the only time that William has that is acting. So the more that he’s acting, the more he can rebuild himself. And so, I would encourage the actor to be at a tabula rasa place, a zero point, a state of absolute emptiness.”