A heavyweight in the pantheon of artists dealing with themes of Black identity, gender, and sexuality, Glenn Ligon is best known for his lusciously smeared and all-but-illegible stencil-based text paintings inspired by the prose of 20th-century figures from James Baldwin to Richard Pryor, via Zora Neale Hurston, Audre Lorde, Jean Genet, and Gertrude Stein.

For his first solo exhibition in New York since 2016, and his first since joining the Hauser & Wirth roster in 2019 (after a decade with Luhring Augustine), the 61-year-old Bronx-born conceptual artist is presenting three distinct bodies of work. The neon sculptures, “debris field” paintings, and text-based works command all three all three floors of the gallery’s 36,000-square-foot Chelsea space.

The exhibition caps off a banner year for the artist, who has been featured in 15 group shows, including the New Museum’s standout exhibition “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” which was conceived by curator Okwui Enwezor shortly before his death from cancer in 2019. That show featured Ligon’s large-scale 2015 neon sculpture A Small Band, bearing the words “blues blood bruise” — a phrase coined by Daniel Hamm, a Black youth accused of murder in a storied 1964 trial — which hung like a glowing flag on the façade of the museum.

Photo by Paul Mpagi Sepuya, courtesy of Hauser & WirthThere is little doubt about Ligon’s Olympian standing, and he was an early choice for art displayed in the Obama White House, which showcased his 1992 Black Like Me No. 2, on loan from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Even so, it’s notable that Hauser & Wirth has dedicated its entire gallery space to a single artist, a first for the global powerhouse dealers.

“The building is ideally situated for two or three separate shows,” says Marc Payot, president and senior partner at Hauser & Wirth, “but we felt the importance of our first show with him in New York, and the absence of him in New York for so long deserves that kind of statement. We don’t plan to do this on a regular basis.”

The star piece of the exhibition is a monumental new triptych, the latest iteration of the artist’s long-running Stranger series that began in 1997 and is based on the James Baldwin essay “Stranger in the Village,” first published by Harper’s Magazine in 1953. The story recounts Baldwin’s stay at the home of a lover in Leukerbad, a remote Swiss mountain hamlet where the villagers had never encountered a Black man.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Hauser & WirthHere, Ligon has replicated in typical, labor-intensive fashion — in stencil with oil stick and gesso on panel — the entire nine-page text of Baldwin’s essay in a richly textured 10-foot-by-45-foot composition. As usual in the artist’s practice, the stenciled letters create a kind of tug-of-war between legibility and illegibility; between pure abstraction and dusty figuration.

As Ligon has observed, “I’m interested in making language into a physical thing.”

As testimony to its appeal, most of the 17 Ligon works that have sold at auction for more than a million dollars are from the Stranger series. This includes Stranger #37 (2008) which, handsomely scaled at 96 by 72 inches, fetched $3.4 million at Sotheby’s New York last December.

Ligon, who was influenced early in his career by the kings of Abstract Expressionism — especially Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Sol LeWitt — made a sharp turn in his practice by the early 1990s, a move he felt necessary to address his own life and times.

Photo by Thomas Barrett“The things I was interested in weren’t in the work and realized I had to change it,” he told Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum of Harlem. His artistic influences also shifted to the likes of Jack Whitten, David Hammons, On Kawara, Félix González-Torres, and Mel Edwards.

That change was evident in the 1993 Whitney Biennial exhibition, which included Ligon’s Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” (1991–93). The multipart work features 91 framed black-and-white homoerotic portraits of nude Black males taken by Robert Mapplethorpe, to which Ligon has added text quoting reactions to the controversial 1986 oeuvre from sources ranging from activists and politicians to religious evangelists. Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” entered the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2001.

Debris Field, a more recent body of large-scale paintings executed in etching ink and acrylic on canvas, makes it clear Ligon has never looked back. The ongoing series, first shown at Regen Projects in Los Angeles in 2019, is by far the most radical of his explorations of language and abstraction. Its isolated fragments of letters drawn or stenciled in black shapes are scattered on cardinal red painted canvas, giving off the syncopated appearance of unreadable shapes on steroids.

Photo by Thomas Barratt“It deals with the language,” says Payot, “or with signs of how much you can reduce something so that it’s still language, or not, and changes to abstraction.”

Only the series title helps to decant the meaning of these eight-foot-high silkscreened works with their Russian Constructivist colors and strong hints of an Andy Warhol red monochrome car crash painting, which evokes the uneasy feeling of viewing a kind of terrible and unfixable wreckage.

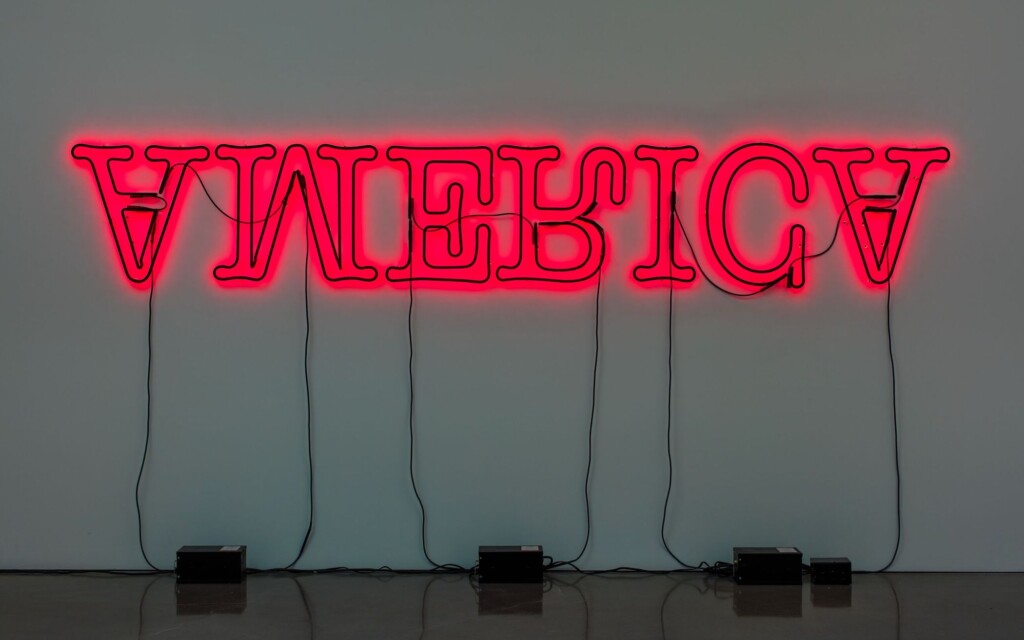

The third leg of Ligon’s massive solo at the Chelsea gallery consists of a suite of new neon sculptures. Since the artist began working with neon in 2006, he has produced a number of important works in the medium, including One Black Day from 2012, with its date of the U.S. presidential election of November 6, 2012, and Untitled (America) from 2018. Both executed in neon, paint, and electrical components, with the latter’s two-foot-high illuminated capital letters that spell out “America” only upside down and transposed, the pieces suggest what might be forthcoming from Ligon’s ever-evolving practice.

“My job is not to produce answers,” Ligon has said of his work, “my job is to produce good questions.”

Glenn Ligon is on at Hauser & Wirth (542 West 22nd Street) from November 10 through December 23