BY JANET MERCEL

For a polyglot artist with a distinctly international life, it may come as a surprise how American Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer seems. But then, the Swiss-born painter left her birth country at just 3 or 4-years old and spent several formative years in Los Angeles before eventually moving to Florence with her father at 11 or 12. There, at 18, she extended her formal training in the Advanced Painting program as one of the youngest students ever accepted at the Florence Academy of Art.

“Does that math add up to 30 years?” she asks, bringing us to the present day at Sapar Contemporary in Tribeca. Nearly a decade ago, Ferrer interned at the gallery while pursuing her art career. Now, she has returned for the opening of her first solo exhibition, “The Scapegoat.” The show is resonant and deceptively layered with themes of sacrifice, suffering, and a profound questioning of higher powers. On opening night, in the bright space on a sharply frigid winter day in New York, the paintings simmer with ancient questions that, as a viewer, evoke intense curiosity about the painter’s point of view.

“I felt a desperation to show their stories—the broader justice or injustice, however you perceive it. The emotional connection I felt while painting them was palpable and energetically very real.” – Emma Kathleen Hepburn Ferrer

Nina Levent, the gallery’s founding director, has told Ferrer that spirituality is in her DNA. Perhaps that connection runs deeper than most—after all, Audrey Hepburn is her grandmother, a woman whose own pathos and suffering as a philanthropist made a lasting impact on the world, as well as a private, internal thread within her family. “In the past, I’ve stumbled on this concept of legacy as outward facing, something that’s passed on only for the public,” Ferrer says. “But she was an artist who took her craft seriously, and there is a creative current that runs between us. She had this incredible feeling for empathy—I see it in my dad, as well. She devoted her later years to helping others, she literally gave her life to it. That feeling is what my painting is about.”

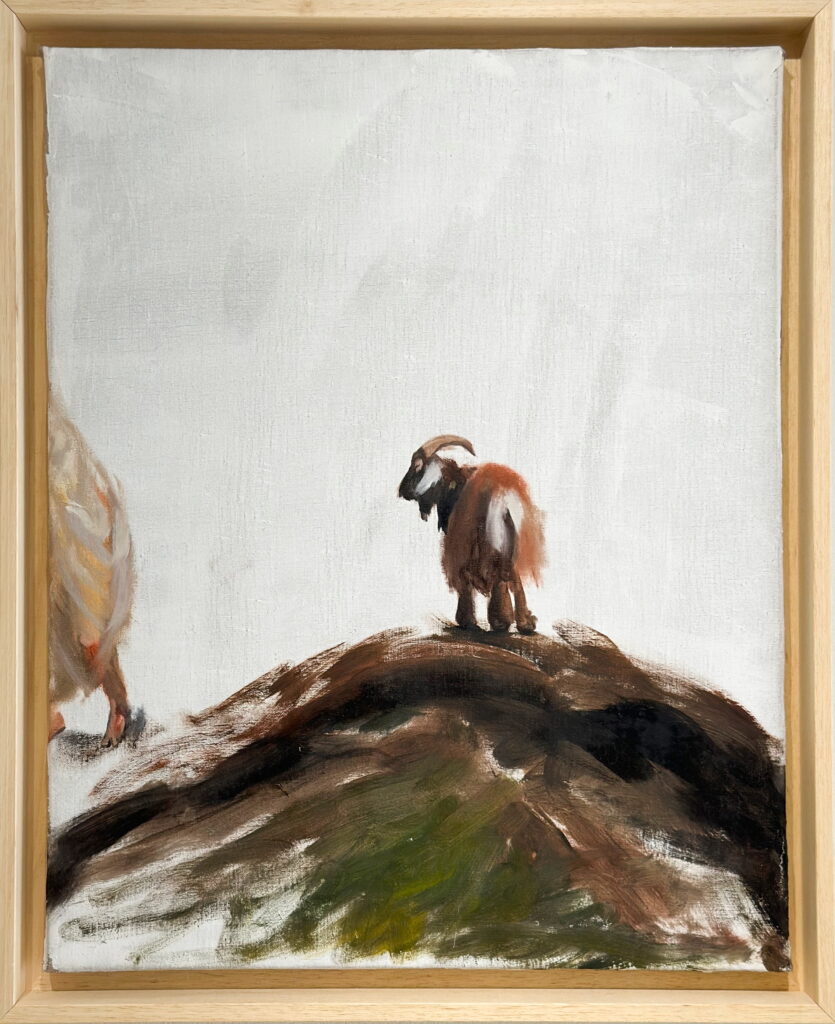

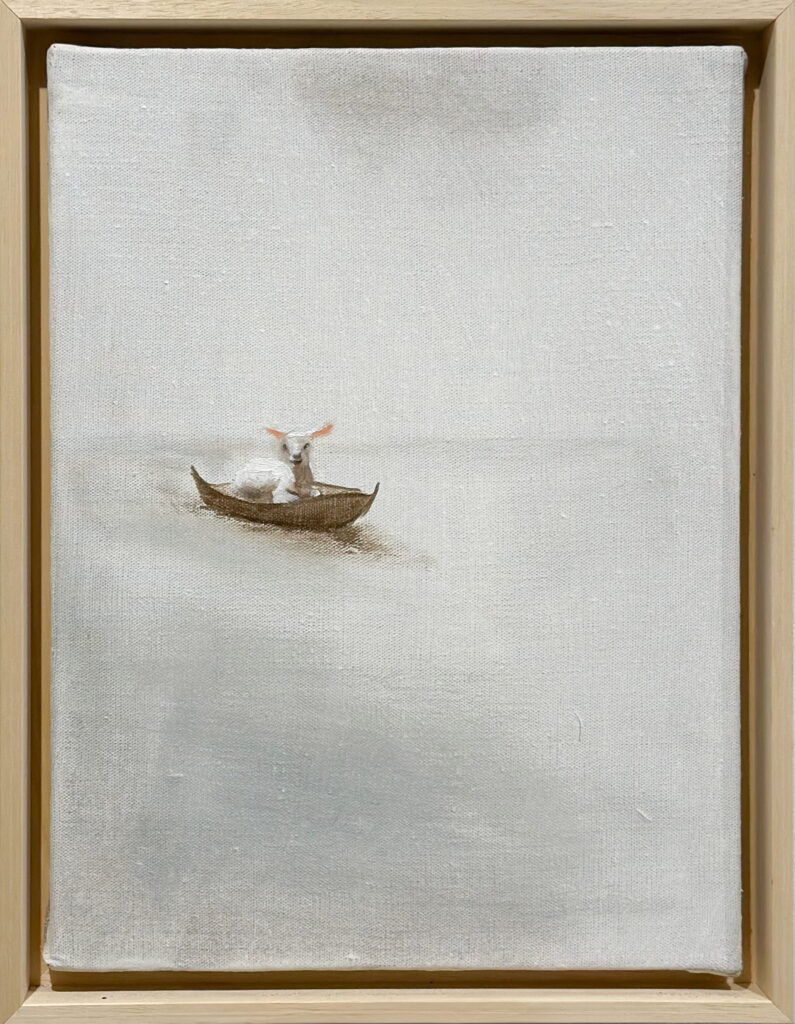

The show’s works, including L’abbandono (Abandonment), Agnus Dei, and Newborn Scapegoat, center on the purification rites of pre-biblical and ancient Greek myth, where communities would symbolically transfer their sin, shame, and afflictions onto a goat and send it into the greaterness. The literal and symbolic “scapegoat” stands for “a million sociological metaphors,” Ferrer describes. “I felt a desperation to show their stories—the broader justice or injustice, however you perceive it. The emotional connection I felt while painting them was palpable and energetically very real.”

In Florence, Ferrer’s training focused heavily on technique, with little theory. Art history was limited to one hour a week, with a focus on a rigorous studio practice. The professors were strict, teaching only a select group of classical painters, never beyond the 19th century. “Tuck your creativity at the door, talent won’t serve you here,” they’d say. “I left knowing how to paint but not having any idea what to do with that,” Ferrer remembers. She dove headlong into the art world, studying under and working for artists like Vincent Desiderio, Will Cotton, and Cynthia Talmadge. She lived in New York for 6 years, doing her time at galleries and liaising with artists. When the pandemic struck, she relocated to Camaiore, a small town in northern Tuscany, where a family home where she’d spent much of her childhood had become her own.

“I bought a one-way ticket, stayed, and built a life there,” she says. “It’s an extremely small town—there’s 40 inhabitants in the village. The roads are often too small for a car.” Surrounded by this rustic, natural place that instinctively felt like home, Ferrer committed in earnest to her painting. Her ideas took shape while studying art history, theology, and philosophy, including at Harvard Extension School and while earning her MFA at Central Saint Martins.

The morning after her vernissage in Tribeca, I tell her that while I understand the academic framework of her paintings, there’s no way I believe her attachment to pain is purely theoretical. “When I moved to Italy I was very ill with an autoimmune disease, frequently in and out of hospitals,” Ferrer tells me. The experience left her examining spirituality, the individual’s role in society and in life, and the nature of empathy, overlapping with the landscape of modern rural Tuscany. “I’m deeply tied to the beauty and aesthetic of Italy, where hunting is a big part of the culture,” she says, “my boyfriend’s family are hunters.” While not particularly religious, it raises conceptual questions for her about the circle of nature, man, animal, and a higher power. It would be a mistake, she says, to ignore how old and intertwined cultural customs are with our species. “My work is not about veganism or climate change, but these contemporary issues are complex. Context is vital.”

Ferrer’s exhibition is deceptively serene; the paintings at first appear almost gentle. Then the animal figures reveal their eeriness—the isolation of a baby lamb (At Sea) or the bloodied toes of a resting frog (You Will Return the Evil to its Steppe (Homage to Zurbarán)). Each work symbolizes the burden placed on society’s sin-eaters: the small, the innocent, the sick, and the weak. “The goat is alone, and it’s heart-wrenching,” Ferrer says. “Is God present for this goat? Is he alone? Does he feel God in these moments?” As Levent explains to me, “Emma sees spirituality not as something tied to a religious institution but as a quality intrinsic to life and creative practice.”

This leads us back to legacy, specifically that of her grandmother. While acting as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, Audrey spent years on field missions from Ethiopia to Turkey, Bangladesh, Thailand, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. She was also, famously, a child of war, living as a Dutch refugee of WWII. “This was totally novel at the time,” Ferrer reminds me. “Multiple trips overseas in a year? There were no Angelina Jolies yet; we weren’t used to seeing the marriage of celebrity and this world in the public eye. And she had been one of those innocent children herself.”

Ferrer, too, works with UNICEF and UNHCR (the UN Refugee Agency) but only recently realized how deeply her painting connects her to Audrey, who passed away shortly before she was born. Does she wonder what her grandmother, one of the most famous film stars to ever live, would think of her work? “Yes, I do. I know you and I might not even be talking today if it weren’t for who I am, and that’s so humbling. I don’t know if I’ll ever live up to it, but I have the privilege to keep working and dedicate myself to my craft. Last night, I invited everyone I knew, from every stage of my life, and reconnected with everyone I could. And I never felt nervous—not once. That felt like a sign that this is 100% right, my identity and my path.

***

“The Scapegoat” runs at Sapar Contemporary from January 9- February 15, 2025