Building a reputation in New York’s nightlife scene can be somewhat of a fool’s errand. Not because of the sleepless nights or the shaky financial grounds upon which all late-night hangouts inevitably stand, but for the singular reason that any new boîte or watering hole will always live in the shadow of Studio 54.

The discotheque founded by Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell was open for just three years between 1977 and 1980 until it was shuttered after a spell of tax evasion, and yet it remains an albatross for those who have deigned to try their hand at playing club king. This included Howard Stein, a fixture on the ’80s disco scene who first burst into the nightlife lexicon when he debuted Xenon, a challenger to Studio 54, with then business partner Peppo Vanini, a Swiss restaurateur who died in 2012, but, in 2018, was accused posthumously of raping a stylist, Phillip Bloch, in the late ’70s.

As fate would have it, Stein and Vanini first crossed paths at Studio and, in a delightfully playful jab of sorts, their new club was named after the chemical element 54. It sat just a few blocks south of Studio 54 at 124 West 43rd Street and, like Studio 54, Xenon was housed in a large theater, once known as Henry Miller’s Theater and later the Avon-at-the-Hudson porn house, until Stein and Vanini took hold. However, the crowd at Xenon was markedly different than those who could weasel past Studio’s infamously strict velvet ropes. The Xenon scene was more fashion, and less Hollywood, according to former mainstays. “Xenon was the only nightclub [in New York City] popular enough to compete with Studio 54,” photographer Bill Bernstein remarked in Night Dancin’ by Vita Miezitis. “It was popular with the straighter, white, upwardly mobile crowd.” The crowd permitted inside was often at the discretion of Stein, who was known to stand at the door alongside his wife at the time, Tawn Christian, “weeding out the detested middle class from the very rich and the colorful poor,” according to a 1980 New York magazine profile. One January 1983 account from inside Xenon recalls Cornelia Guest’s attempt at an onstage turn from debutante to rock star at an after-party for the Gold and Silver Ball. She sang (backed by a faux band), danced, drank, and smoked until 3 AM.

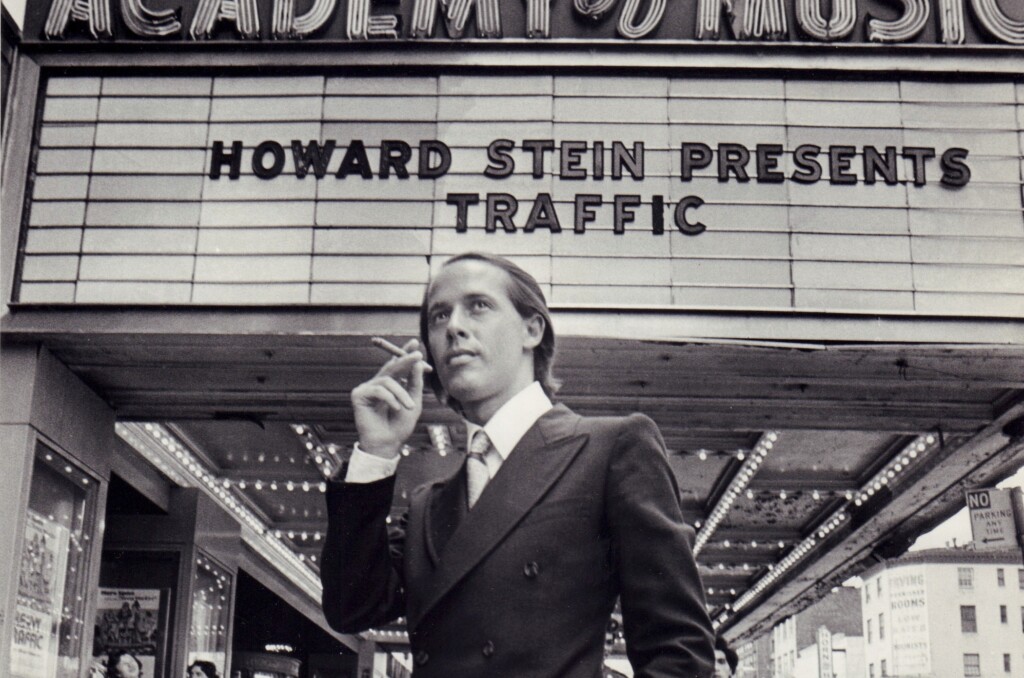

After-hours habitués were in no short supply in Stein’s Rolodex. Prior to Xenon, Stein spent his early years in Manhattan as a party promoter, music manager, and proprietor of Howard Stein’s Academy of Music, which opened in 1971 on East 14th Street (and later became another nightlife mainstay, the Palladium). Here Stein could be found holding court in a suit and tie, catering to the likes of Bob Dylan, Roxy Music, Black Sabbath, and Lou Reed, whose December 21, 1973, show at the venue was released as the Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal live album. In 1973, Stein threw a notorious Halloween party at the Waldorf Astoria, headlined by the New York Dolls, where scantily clad socialites shimmied alongside mummies and mustachioed men dressed as nuns. In 1975, Stein joined Diana Ross as her date for a headlining performance at the opening of the Westchester Theater, a bacchanal he helped to plan.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesAnd though he always remained polished, Stein was a night wolf in sheep’s clothing. “Howard Stein is a New Yorker,” Anthony Haden-Guest surmised in his nightlife anthology, The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night. “A springy, dapper man, his black hair slick as polish on a balding pate, he has a bright grin but can switch from charm to chill in a nanosecond.” He couldn’t stay away for long following the closure of Xenon in 1984 as nightlife’s center of gravity shifted away from Midtown. In 1987 came Au Bar, a subterranean hot spot that Stein referred to as “a quiet, safe refuge from the jungle” inspired by English members’ clubs. The reviews were mixed, and he often found himself in the crosshairs of Page Six gossip columnist Richard Johnson, who relentlessly barbed Stein in his column with the seemingly unrelated detail that Stein’s father, Charles “Ruby” Stein, a loan shark and Colombo crime family associate and pal of Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, was rubbed-out by the Westies and his headless body was found floating in Jamaica Bay.

“[Au Bar] is located in the basement of an office building on East 58th Street,” one biting account by journalist Patricia Morrisroe read following its opening. “There’s no name outside. Just the usual status symbols: two power-hungry doormen, six yards of rope, and a desperate crowd. Inside, it’s very English with mix-and-match sconces, imported wainscoting, leather books, and antique table coverings that are falling apart after three months of drinks and dinners. For now, [Stein] is enjoying life at the top, waving at the middle-aged men with their gold Rolexes, their skin gleaming with après-tan cream. The women, their faces very pale — who wants to ruin the cosmetic work? — blow kisses at him and say he looks wonderful.”

Though people declined at the door would skulk away with disgruntled accounts, the guest list remained as strong as ever, with the Kennedy clan frequenting the uptown basement, namely John F. Kennedy Jr., who was known to affectionately refer to Stein and Vanini as his “disco daddies.” “John-John was special,” Stein said of JFK Jr. in a 1989 profile of the political heir where he, in turn, referred to himself as John’s “Disco Uncle.” “He was less a disco baby. He was shier, ingenuous. He didn’t leverage his name off the way kids of the famous do in my world. He had star quality. So, every time he was there, he got his picture in the papers. It took a scandal for the other Kennedy kids to be photographed.”

Au Bar enjoyed a nearly 20-year run that ebbed and flowed across generations, with other Stein ventures along the way: Prima Donna, System, Rock Lounge, and Gertrude’s, which was later reimagined by Stein’s daughter as Brown’s, to name a few. Stein died at age 62 in 2007 after battling kidney cancer. These days they all serve as revered reference points for the bullish nightlife figures of today and tomorrow, driven by the mystique of Howard Stein.