As the saying goes, bad things happen to good people. Thanks to karma, bad things happen to bad people, too. Or, at least, a bad thing happened to the financier James “Jubilee Jim” Fisk Jr. While the Gilded Age robber baron never faced repercussions for creating a panic on gold in 1869, he did die at the hands of a jilted business partner, with whom he was in a bitter love triangle. And thus, his murder completely overshadowed his dirty business dealings — even the one that almost besmirched a presidential office.

Fisk was born on April Fool’s Day in Pownal, Vermont, in 1835. The son of a humble peddler, he ran away from home at 15 to join the circus, only to eventually return and settle down. At 19, he married Lucy Moore and, like his father, became a salesman. Later, during the Civil War, he made money selling fabric to the government. But his financial situation didn’t take a turn until the war was over, when he used a hot tip to make some quick cash.

Upon learning that the war was coming to an end, Fisk sent an agent to London to short sell Confederate stocks. This entailed loaning stocks from a broker only to immediately sell them. When the stock prices crashed (as Fisk knew they would), he bought them back at a much lower price, returned them to the broker for the original loan price, and pocketed the difference. It was a 19th-century version of The Big Short — and it wouldn’t be the last time Fisk tried the trick. By 1864 Fisk had moved to New York to work as a stockbroker, landing in the offices of Daniel Drew, famously helping him wrestle the Erie Railroad away from Cornelius Vanderbilt by manipulating the company’s stocks. While there, Fisk met Jay Gould, and a terrible twosome was born. The duo bribed judges and legislators and colluded with politicians. But their biggest scheme involved gold and the president of the United States. It was a disaster that became known as “Black Friday.”

Photo via National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian InstitutionWhen Ulysses S. Grant assumed the presidency, the economy was in near shambles, and the country was in debt. To fix this, the treasury began selling off its gold, putting it into public circulation. Fisk and Gould hatched a plan to slow the government’s gold sale, while also buying as much of it as possible. This would drive up demand, and thus its value, earning Fisk and Gould a hefty return on investment.

They teamed up with a man named Abel Corbin, who was married to President Grant’s younger sister, to gain access to the president in an effort to manipulate him into stopping the sale of government gold. Grant didn’t fall for it. To make matters worse, when he eventually found out about the scheme, he released $4 million worth of the government’s gold into the market. Gold prices plunged, taking the rest of the stock market — and the economy — down with them.

The entire debacle became a massive blight on Grant’s time in office. A congressional investigation was held, and because of the Corbin connection and that Grant had been seen with Fisk and Gould, many believed he was in on their plans (although he was officially declared innocent). Thanks to a team of lawyers, Fisk also avoided consequences — but his luck was about to run out.

During his rise in New York as a stockbroker, Fisk was something of a ladies’ man, who flirted by passing out $100 bills (the equivalent of giving $2,000 to a cute stranger at a bar today). His wife, who lived in Boston (and with whom he was very close), didn’t mind his philandering. It is believed she had a girlfriend of her own.

Photo via Corbis Historical/Getty ImagesAt the home of a mutual friend, he met Josie Mansfield, a struggling actress and divorcée in dire financial straits. She successfully wooed him by rejecting his usual $100 bill trick, but eventually got him to subsidize her rent, fill her closet with new dresses, outfit her with a variety of jewels, and fork over cold, hard cash. It was a very lavish, very public romance that was gossip fodder for high society at the time. Sadly, her affections waned in 1870 when she fell in love with Edward Stiles Stokes, a married associate of Fisk’s. Mansfield and Stokes left their respective partners to be together, but not even love could make up for Fisk’s money.

Mansfield attempted to extort funds from her former beau by threatening to publish their private correspondence, which she claimed proved his business malpractices. Stokes also threatened to blackmail Fisk, but the financier wouldn’t budge. He instead began a legal battle for the return of his letters, and for Stokes’s share of stocks in a Brooklyn oil refinery they were in business together on. Fisk won both suits, enraging Stokes.

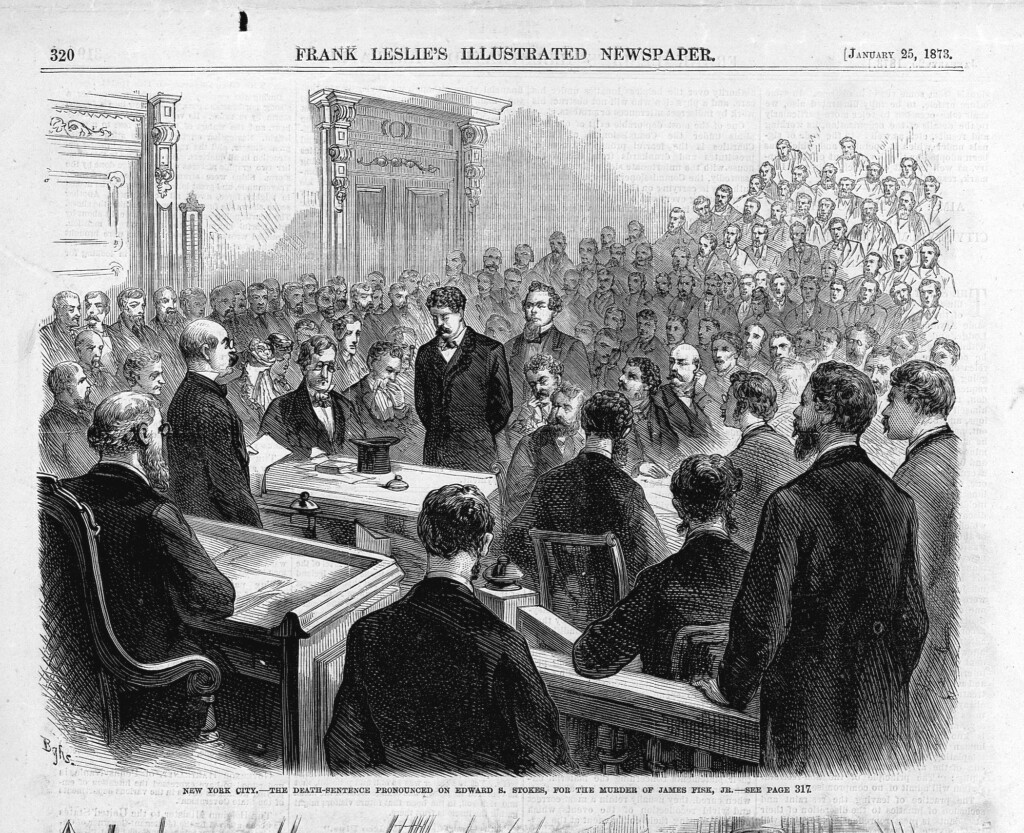

On the afternoon of January 6, 1872, Stokes confronted Fisk at the then-new Grand Central Hotel in the East Village and shot him twice. According to the Library of Congress, Fisk shouted, “For God’s sake, will no one save me?” as he fell. It was a slow, painful death (Fisk didn’t pass away until the following morning), but it ensured he was able to identify Stokes as the shooter, who was apprehended quickly.

Photo via National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian InstitutionBy many accounts, Fisk was a notable rogue of the Gilded Age, villainized by high society for his scandalous affairs, brazen manipulation of the stock market, and the garish way he displayed his wealth. But, ultimately, save for being immortalized in the 1937 film The Toast of New York (which played fast and loose with the facts), he didn’t achieve the legacy that his fellow robber barons — like John Jacob Astor, J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Vanderbilt — did. Perhaps if he had lived longer (Fisk was only 36 when he died), he would have had ample time to build a more lasting legacy. Or, at least, add a few more high-profile crimes to his CV.

The New York Times’s account of the murder summed his life up best: “Here is a man who for years the world has called by the hardest and most opprobrious names, sent with scarcely a moment’s warning to his endless doom, and by one who, to say the least of it, is no better than he should be.”