On a recent Saturday morning, the architect and art collector Peter Marino was driving to the airport from his estate in Southampton, en route to Los Angeles, and reflecting on the changes of the past year.

“I used to brag that I’d go to the grave never having turned on a computer, but now I’m on Zoom eight hours a day,” he lamented. “I really thought I’d be able to grow my hair out and take the air in the Hamptons for a while, but if anything, [my schedule] has gotten worse.”

He wasn’t kidding. While he has managed to grow out his hair somewhat (“I look like a Russian intellectual”) and play tennis with his new Peruvian trainer, the stock market has been performing so well the residential side of his business had doubled. There’s a giant condominium in Miami that needs completing, as well as a sprawling private property and resort for Dmitry Rybolovlev on the Greek island of Skorpios, which the Russian oligarch bought in 2013 from Aristotle Onassis’s granddaughter, Athina. (Originally owned by Ari, the 205-acre island was the setting for his 1968 wedding to Jackie.) “It’s the biggest project of my life,” Marino said, not for the last time during our conversation. “It’s a dream.”

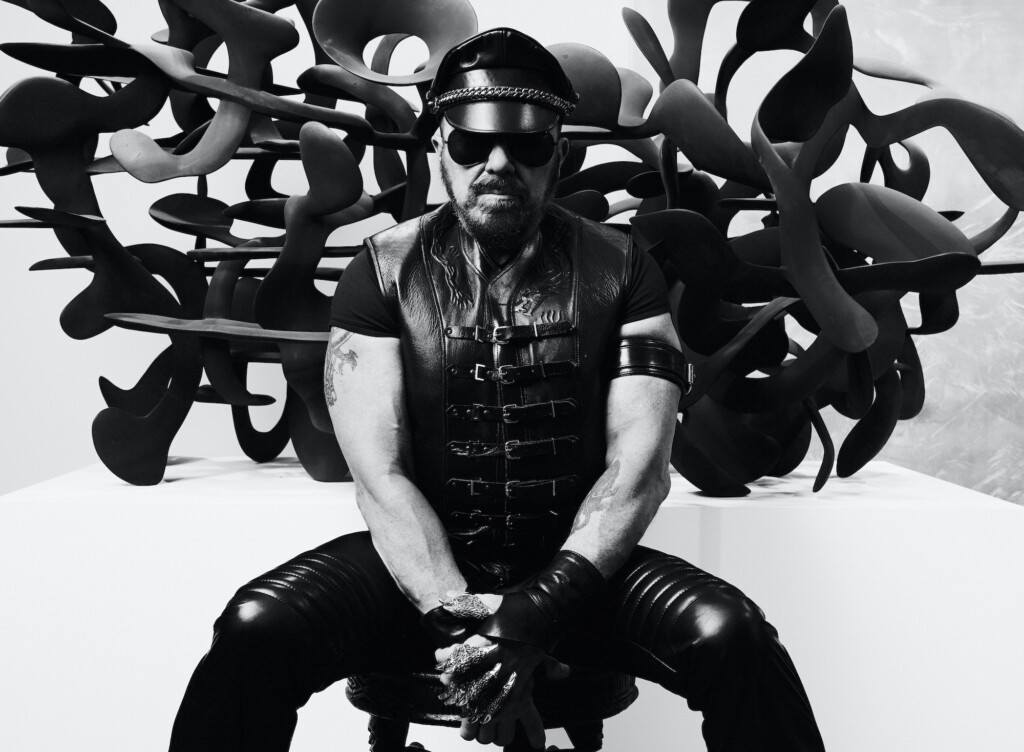

Photo by Manolo Yllera, courtesy of Peter MarinoBecause of his stranglehold on big-ticket store designs for the likes of Chanel, Dior, and Louis Vuitton, Marino is sometimes known as the “King of Retail.”

To his surprise, given the pandemic, his commercial work has also ballooned. “I thought all the brands would go into hibernation,” he said. “But for companies that are well financed — and let’s face it, a lot of these brands are really just real estate holding companies that own these buildings and will be fine — they look at this as a moment of opportunity. They’ve all said, ‘Business is slow anyway, so let’s renovate all our stores.’”

As a result, Marino is currently redoing the Christian Dior Paris flagship, on Avenue Montaigne, that he first designed in 1995, doubling the size, and adding two glassed-in gardens to the courtyard. There is also a new Bulgari store on the Place Vendôme in Paris; a new Louis Vuitton store in the Namiki district of Tokyo; and two new Chanel stores, in Miami’s Design District and Beverly Hills.

“The reason Peter has so many luxury clients,” says the design critic Pilar Viladas, “is that he understands the DNA of each one, and designs accordingly, expressing what makes each brand unique. Louis Vuitton stores do not look like Chanel stores, which do not look like Bulgari stores.”

Photo courtesy of Peter MarinoMarino is also applying his considerable customer focus and taste to ongoing large-scale projects such as an ambitious new Cheval Blanc hotel spanning two city blocks in downtown Los Angeles, and the much-anticipated new La Samaritaine Paris hotel, on the site of the historic former department store of the same name.

Located on the Right Bank, a beret’s toss from the Louvre, the La Samaritaine building was acquired by LVMH in 2001 and, after an extended gestation period, has been reimagined as a mixed-use development slated to open this summer. The five-star, multiuse 72-room hotel overlooks the Seine and boasts a view of the Eiffel Tower from every room.

It will also, Marino added, his voice becoming increasingly animated, be “the biggest project of my life” and the only five-star hotel in Paris that is wholly owned by the French. “Everything else is either Gulf or Chinese money,” he noted. “We made a big effort to have everything inside done by French artisans and artists, such as Ingrid Donat, who made the bronze bar and grills for the lobby. I think it’ll have a very special flavor.”

Though his tentacles extend to all corners of the globe, and he has spent a large part of his adult life flying, his trips have become increasingly rare and strictly domestic. “I miss the social interaction of travel because I learn so much from my clients — they all have such interesting international lives,” he said. “But it’s a great, great, blessing to have a break from it all, and I’m convinced it’ll add 10 years to my life.”

Photo by Sébastien Agnetti (13 Photo)/ReduxThe time in the Hamptons, an enclave he has visited his entire life (don’t get him started on how kids today don’t know that the Hamptons used to be famed for its potatoes), has allowed him to focus on his latest labor of love, a namesake art foundation in Southampton Village opening in June. An 8,000-square-foot “mini-Frick” as he referred to it, the Peter Marino Art Foundation will house his not inconsiderable collection of paintings, sculptures, decorations, and collectibles.

“It’ll be artwork that I own, from 5,000 BC to the present,” he explained. “Everything from ancient Egyptian art to Delacroix next to all of my de Koonings, Twomblys, and everything in between. Not too shabby. It’s important for the town of Southampton, and I’m anxious to see people’s reactions.”

The foundation is in the former Rogers Memorial Library Building, next door to the Southampton Arts Center, built by the venerated local architect R. H. Robertson. Marino decided to buy the building after driving by it with his wife, the costume designer Jane Trapnell. “There was this group of people whitewashing it and turning it into a Bed Bath & Beyond,” he recalls. “There’s not a lot of great architecture in Long Island, and I was so disgusted at the lack of reverence and relevance that I went through great efforts to buy it and restore it.”

Marino has scrapped plans for a documentary about himself, he says, because he wasn’t happy with the footage after two years of being tailed by a film crew. But the foundation — not to mention his efforts as the chairman of Venetian Heritage and its herculean attempt to restore the Palazzo Grimani and its original artworks — suggests that Marino is preoccupied with the idea of leaving a mark in an often-transient profession.

Photo by Manolo Yllera, courtesy of Peter Marino

Photo by Luc Castel, courtesy of The Bass“It’s absolutely on my mind,” he acknowledged, “a little bit of permanence is an architect’s dream. Nobody would ever dream of painting over the Mona Lisa. But architecture is constantly being knocked down and rebuilt. There is a real lack of reverence for architecture, and that’s always disturbed me.”

It’s the same quest for longevity that informs the sculpted bronze boxes and hulking doors (each weighing several hundred pounds) that he creates and exhibits, most notably at the Gagosian Gallery in London in 2017. “These things are built to last,” he said, “and will be part of my legacy.” It’s an impulse that is also palpable in The Architecture of Chanel (Phaidon), a new book out in October that celebrates the 12 buildings that Marino has created for the brand in the last 15 years.

“I’m very proud of the book,” Marino said. “I can’t imagine any brand other than Chanel giving me the carte blanche and the freedom to create retail experiences that are like art. But retail architecture doesn’t always last long — the building we did in Osaka has already been destroyed — so I wanted a record of it all.”

One thing he doesn’t have to worry about is having a chronicle of the signature leather outfits that have become as much of a part of his mythology as his gleaming steel and glass towers. His stubbornly personal aesthetic (even places with strict dress codes, such as the University Club, eventually yield to him) is much photographed de-spite his wearing only barely discernible variations on a theme.

Most of his leather togs are custom made, including molded pieces by Joan Bergin, the costume designer known for her work on The Tudors. And while he is not above experimentation — he recently had some peasant shirts he liked replicated in black leather and has been collecting enormous black pearls to make into a choker to wear to the opening of his foundation — don’t expect him to toe the company line and step out in one-of-a-kind Chanel anytime soon.

“Karl [Lagerfeld] made me the odd leather piece,” he admitted. “But remember, Chanel is the only brand left standing that does not do menswear, and a tight little tweed skirt is not my look.” Besides, he explained, he always remembers what the late Chanel designer told him at dinner one night.

“Karl said to me, ‘Peter, do you realize that apart from Mao Zedong, you and I are probably the most recognizable people in the world?’ It was funny at the time, but it really struck me as an important lesson if you want people to remember you.”