Dr. Max Jacobson, a.k.a “Dr. Feelgood,” poked A-Listers from Marilyn to Elvis with his dangerously addictive “IV Special” – until the Feds shut down his Upper East Side drug mill.

John F. Kennedy with Dr. Max Jacobson (right)

In the spring of 1962, President John F. Kennedy is said to have raced down a hallway of the Carlyle hotel stark naked. The incident (which would have jeopardized his presidency) was kept from the public. Also unbeknownst to the public, and Kennedy himself, was that he was hooked on amphetamines. More astonishingly, his supplier was a medical professional, Dr. Max Jacobson, whose dangerous remedies were inflicted upon a generation of New York’s elite.

Born in 1900 in Fordon, Bromberg, then part of the German Empire, Jacobson, who was Jewish, moved to the United States in 1936 to flee the Nazis. There, he slowly built his practice and a reputation for himself. Known as “Miracle Max,” the list of Jacobson’s regular patients reads like a roll call of the 20th century’s biggest icons: Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, Leonard Bernstein, Judy Garland, Humphrey Bogart, Elizabeth Taylor, Cecil B. DeMille, and Liza Minnelli; writers like Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Rod Serling, who created The Twilight Zone; and even Nelson Rockefeller.

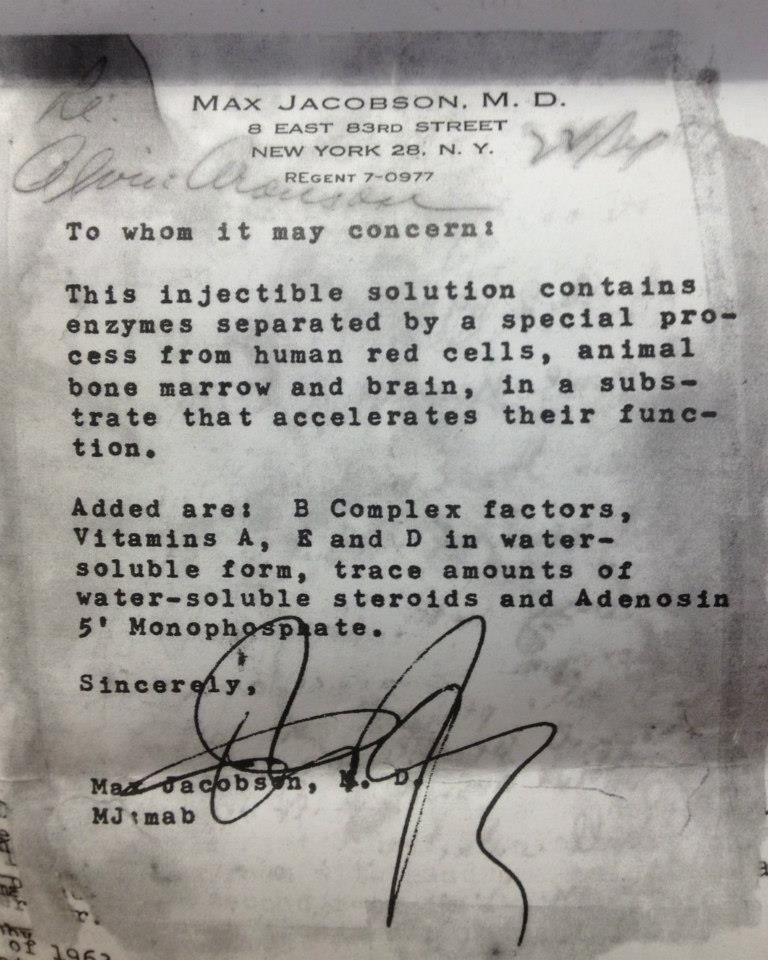

Jacobson amassed his clientele thanks to his “IV Special,” a booster shot which he doled out at his Upper East Side office around the clock, often seeing patients at 3 AM. He was mum about what was in the mysterious vials and his patients didn’t ask, gladly letting the doctor jab them with a syringe in a quest for more energy, weight loss, and pain relief. Capote, who struggled with addiction most of his life, described the injections as “instant euphoria — flying, like Superman,” adding, “Ideas come at the speed of light. You don’t sleep, nor do you need to eat. If its sex you’re after, you can have all you want and go all night.”

What made Jacobson’s patients feel so good was reportedly a truly crazy concoction that included 28 milligrams of methamphetamine, human placenta, monkey gonads, sheep sperm, and steroids. It was a highly addictive (and deadly) recipe that only a mad scientist could dream up. Tennessee Williams immediately got hooked on the injections, falsely believing he was being pricked with a vitamin B12 shot. Williams said he felt “as a bird on a wing — I was released.” Jacobson, who once had an interest in treating multiple sclerosis before discovering that biochemistry could get him rich fast, never examined patients or made real diagnoses, preferring to reach for the hypodermic needle instead. He claimed his injections could rescue singers who had lost their voice, cure writer’s block, and combat stage fright for actors.

Jacobson’s most famous patient was John F. Kennedy (and his wife, Jackie). The doctor’s relationship with the family was so close that he traveled with the then-president on Air Force One, made house calls to see him in Hyannis Port and Palm Beach, and visited the White House 34 times over the course of 20 months. His presence was so frequent that the Secret Service dubbed him “Dr. Feelgood,” and the nickname stuck.

Kennedy first met Jacobson through Chuck Spalding, an old and trusted friend from his Harvard days. In September 1960, Kennedy was preparing to debate Nixon in the first televised presidential debate. He had lost his voice, felt fatigued, and complained of constant back pain. Jacobson injected his “energy formula” into Kennedy’s larynx and JFK’s commanding voice returned, full throttle. Kennedy ended up crushing Nixon in the debate, a swing moment in the election that he would go on to win. He began to call Jacobson regularly, using the code name “Mrs. Dunn” when he would ring the doctor in his New York office. Naturally, Jacobson was ecstatic about the connection. “He made me feel whatever I said was meaningful,” Jacobson wrote in his unpublished memoir. “And all-important was my advice.”

Dr. Max Jacobson, a.k.a “Dr. Feelgood”

When Kennedy was in the White House, Jacobson, with his signature thick eyeglasses and German accent, became part of the inner circle. He was a guest at the inauguration and the president’s birthday party at Madison Square Garden. He flew with the president to summit meetings in Paris and Vienna, when Kennedy met with Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader, in the summer of 1961. Khrushchev was late for the pivotal meeting and the poke Jacobson had given Kennedy was wearing off. The doctor injected the president two more times to give him that extra energy he thought he needed to discuss critical world affairs. Jacobson was so entwined in Kennedy’s personal orbit that his laboratory in Point Lookout, New York, said to reek of cigarette smoke and formaldehyde, was co-owned by JFK’s brother-in-law Prince “Stash” Radziwill, who was married to Jackie’s sister Lee at the time.

But their close relationship came to a crash after the Carlyle hotel streaking incident. It was clear to those around him that Kennedy was hooked on Jacobson’s injections and was displaying increasingly erratic behavior. Side effects of the potent drug combo included hyperactivity, nervousness, wild mood swings, hypersexuality, hyper-grandiose paranoia, and impaired judgement. When the president’s brother Robert confronted him about his drug use, Kennedy was said to protest: “I don’t care if it’s horse piss, it works!”

Finally, Hans Kraus, Kennedy’s New York-based orthopedic surgeon, intervened, warning JFK: “No president with his finger on the red button has any business taking stuff like that.” Kraus threatened to expose Kennedy’s reliance on Jacobson unless it ceased immediately. That year, Jacobson was officially banned from the White House for good. Kennedy’s staff observed that his leadership quickly improved, especially during the critical Cuban Missile Crisis in late 1962. While Kennedy was able to bounce back, not all of Jacobson’s patients were so lucky.

In 1961, Jacobson injected Mickey Mantle’s hip with his concoction, causing a severe abscessing septic infection that sidelined the Yankee’s star center fielder. At the time, no one in Mantle’s camp pointed a finger at Jacobson and his speed shots. Mantle’s illness was instead blamed on his alcoholism and self-destructive lifestyle.

Then, in 1969, onetime presidential photographer Mark Shaw (who often piloted Jacobson in his small plane to see Kennedy), passed away at age 47. The autopsy revealed Shaw had died from “acute and chronic intravenous amphetamine poisoning.”

Around this time, the heat started homing in on Jacobson and his drug mill-cum-office on the Upper East Side. An investigation was opened in 1970, but it wasn’t until a scathing 1972 New York Times article exposing Jacobson’s shady practice that things really unraveled. A year later, Jacobson had his office raided. His staff admitted to buying huge quantities of amphetamines to give patients at high-level doses. In fact, Jacobson ordered 80 grams of amphetamines each month, enough to make 100 very strong doses of 25 milligrams each day. The Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs seized the supply and the New York State Department of Education and the attorney general’s office submitted “charges of unprofessional conduct and fraud in the practice of medicine.”

Dr. Jacobson’s shots proved lethal to some patients

In 1975, Jacobson’s license was revoked. He applied to have his license reinstated at the age of 79 in 1979, but his request was flatly denied. By this point, Jacobson’s own speed use had gone into overdrive, keeping him awake for days on end in a drug-induced state. He died later that year in New York and was buried next to his second wife, Nina (who died of a speed overdose in ’64), and his parents in Mount Hebron Cemetery. But Jacobson’s death had one (no pun intended) high note: his funeral service took place at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on Madison Avenue, where many of his celebrity patients, like Jackie O., Lauren Bacall, and Montgomery Clift, were also memorialized.