Hidden away from the mainland, Little Palm Island and Bungalows Key Largo are the ultimate tropical escapes—just a drive and short boat ride from the chaos of Florida’s overrun tourist resorts. MICKEY MCCRANOR checks in and savors the seclusion.

The route to Little Palm Island is 71 miles on Route 1, a slender expanse of pavement and bright blue sky made famous by Ralston Crawford’s 1939 painting Overseas Highway. Crawford’s stark monotone choice of color for the sky is surprisingly accurate—there is not a cloud to be seen.

Rebuilt after 2017’s Hurricane Irma, the almost five-acre property is entirely removed from the mainland—cars cannot access the Bungalows at Little Palm Island, so, after checking in and being handed a Gumby Slumber cocktail (one part pineapple, cranberry, orange, and rum, garnished with coconut), we are walked to a private dock with a boat waiting.

The boat is captained by a man with a handsomely cropped beard and sun-soaked skin. The seaman is so accustomed to this journey that he completes our trip with an array of effortless motions while gabbing away. The Truman (named after President Harry S. Truman) is a 15-foot wooden boat accented with brass ties and plates, freshly painted and polished to a shine. It is a hint of what’s to come: timeless elegance and complete privacy. Arriving by car to Little Palm Island seems somehow improper.

Formerly known as Little Munson Island, the rechristened Little Palm Island has two claims to fame. The first: it was the favored vacation destination of the aforementioned President Truman. The second is its abundance of torchwood trees—named for their naturally high resin that burns so well it was originally used for torches. Torchwoods tower over the property, creating a lush and thick brush on the island. Sadly, Hurricane Irma ravaged significant damage to the grounds, but they rebuilt what they could and nourished everything that survived. A lone outhouse still serves as the island’s telephone booth and the grand lobby’s piano remains intact. “Not even a hurricane could move that,” our guide quips.

Despite the rebuilding, the resort still feels both lived-in and well-maintained, from the teak floors to the thatched roofs. As we enter the main building, the crickety-creak of the hardwood floor under our feet is the only soundtrack. Cell phones are not allowed in common areas. There is no loud music or boisterous conversations. Images of President Truman and his wife, Bess, adorn the walls in the main hall, which has the island’s only television. Forget bingeing Netflix while on Little Palm Island—there are no TVs in the rooms. This electronic-free vibe is in synch with Little Palm’s motto: “Get Lost.” Even in the most populated area of the resort—the central pool and tiki bar—the air is filled only with the gentle break of the waves nearby and the distant, wistful sounds of mourning doves.

The distance between one end of the island and the other is a thousand feet. At most, the path from the dining hall—a sprawling two-story Cuban lignum vitae wood chalet that houses the resort’s bar, the aptly decorated Monkey Hut with its apparently unmovable piano—to the east end dock, which can accommodate private sea planes and yachts, could take anywhere from just five minutes or up to two hours if you were interested. We opt for the latter to investigate and discover the island’s coconut palms, large flows of wild dilly, reddish egrets, Key West piping plovers, and the very insistent eastern narrow-mouthed toads.

Getting lost on an island that covers less than five acres was surprisingly easy. After our explorations, we arrive in our cabin to a bottle of champagne. The cabin itself is instantly cozy, embracing its natural wood motif with acacia light boxes that display island tchotchkes above polished heart pine furniture and a four-post bed complete with a gossamer linen canopy.

Outside, a staircase leads to our private beach, a fire pit, and a massive copper tub, perfectly sized for two. We continued our escape to the resort’s other secluded beaches which have access to kayaks, waterboards, water bikes, and a dock that can be used to charter a trip the island’s historically significant fishing spots. The great catch is what first brought President Truman here—for local blackfin tuna and mahi-mahi. If you are skilled or lucky enough to reel in any impressive catches, the resort’s kitchen will clean, cut, and cook it for your dinner that same night.

The easiest place to feel blissfully lost are those quiet, meditative pathways that weave through the island’s palm tree canopy. Even the task of keeping the pathways clear of the previous night’s wayward leaves is quiet and calm: no wind blowers or lawn mowers here. Everything is done by hand and with meticulous care.

There is just one restaurant on the island, Chef Richard Fuentes’s Dining Room, but the menu changes daily. The five-course dinner included island staples like Key West pink shrimp and freshly shucked oysters, but also boasted fabulous steak and caviar dishes. The tuna tartare and salmon sashimi were delicate delights and par nicely with a Joseph Phelps pinot noir or signature cocktails made with Papa’s Pilar dark rum. While we waited for our next course, a standout was the sorbet palette cleanser in tart cherry and refreshing watermelon complete with the unexpected addition of crackling Pop Rocks candy.

Little Palm’s success lies in an unwavering dedication to the “Get Lost” mantra and commitment to remaining a secluded paradise. It’s no surprise that the resort is a favorite getaway for U.S. presidents and celebrities. It was incredibly easy to follow Little Palm’s advice and just get lost on an island getaway without the hassle of getting to an island.

BUNGALOWS KEY LARGO

Key Largo’s more rural approach from Florida’s Miami-Dade County is a thin strip of asphalt surrounded on both sides by native buttonwood trees, the reaching, grasping branches and low canopy so thick in some places that it can be hard to see the glittering water waiting beyond them. This quiet patch of highway guides you in by way of the Mosquito Creek Bridge to a pin-straight slab of concrete buttressed on both ends by murky swamplands known as Crocodile Lake. The occasional bougainvillea or frangipani tree stand out amongst an otherwise impenetrable wall of green. Key Largo makes itself clear up front: nestled in the heart of untamed nature is an equally unspoiled oasis.

Wild cotton trees creep over the murky wildlife reserve, hovering above a pitch-black sheet, whose placid surface gives no indication of its depth or activity below the surface. Battered palm trees and hurricane-proof utility poles serve as a gentle reminder that nature is not far from reclaiming this island. In fact, many of its earliest European inhabitants were survivors from ships wrecked off its shores. It came to fame in the 1948 film Key Largo starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, but it proved inhospitable for filming so was recreated on a Hollywood soundstage. It is still most well-known for its diving industry, where those with adequate courage and preparation attempt to go face-to-face with its unforgiving and unexplored underwater chaparral.

Wildlife seems to creep into every crevice of unconquered land. Wild chickens claim their parking lot territories with loud cackling. Foot-tall Florida thatch and sea oats occupy small spaces between scuba instructing facilities and boat rentals. Sun-bleached Key lime pie stands don paint that doesn’t seem to last against salt-soaked air and brutal marine-layer winds.

Even still, there are reminders that the real world exists. Fast food restaurants have been installed. Firework stands boast wares capable of large and loud controlled explosions. Big trucks driven by impatient contractors serve as noisy reminders that the real world is not that far away. The drive in from Miami was just over an hour, made longer by stops to take in the sights or to argue over whether crocodiles or alligators roam the waters (it’s both).

In an act of defiance in this milieu is Bungalows Key Largo.

Bungalows embraces the idea of existing within the native flora and fauna. Pulling into the teal painted gate is a cabana-style valet stand. Attendants sport sholapith hats and impeccably white uniforms that stand out against the green and brown aura of the reception lobby’s central attraction: a reclaimed Jamaican dogwood tree. The lobby is decorated with vintage cameras and photographs of rippling seasides and well-worn skiffs. This is perhaps a premonition (or possibly a suggestion) of your upcoming temporary occupation as an auteur of sunset photographs. The opportunities to take these are as easy as they are to enjoy.

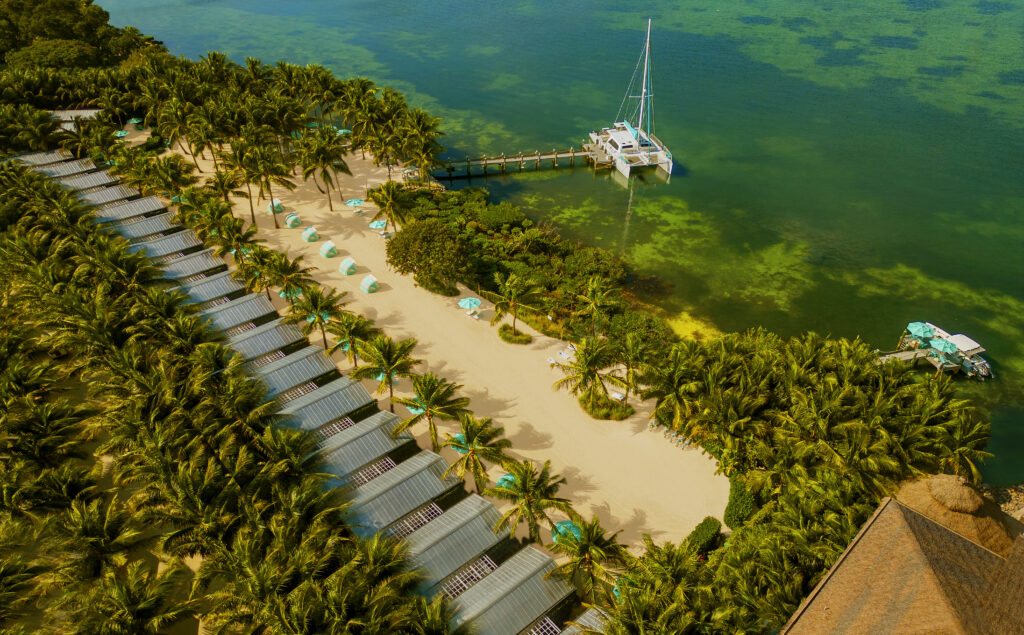

Once checked in, you are handed a map and assigned a tour guide. The property’s waterfront occupies, at most, 1,500 feet from the eastern hammocks. Taking a walking tour from one end of the beach to the other could occupy 20 minutes, but a New Yorker could accomplish a full survey of the beachfront in 10 minutes.

So why the map and guide? Our ingress to the property began with the theatrical breach of a large teal-color gate. As it creaked open, commanded by an unseen device on our electric-powered buggy, our tour guide began down a long pathway of palm trees, wooden signposts, and bicycles. His monologue, no doubt honed over dozens, if not hundreds, of similar trips, gave us the lay of the land.

The seafood restaurant, Fish Tales; the Hemingway Bar (themed after the famed Keys resident); and the 25-foot floating flamingo are all within a stone’s throw of our bungalow. What seemed to stick was that this tour was born of necessity as well as accommodation. Once situated and ready to take in the property, there is an immediate sense of seclusion. There is no high-rise central office or multistory central complex here. This place gives the impression that you are here and here is very far away from there (wherever there might be).

Even the bungalow itself is a haven. The porch faces no other rooms, with no elevator to spoil the experience. There are no ice machines or abstract paintings on the hallway walls. In fact, there are no hallways. The source of light during the day comes from our outdoor patio and cabana, complete with a large porcelain tub and waterfall shower that is hidden and covered by the palm foliage and bleeding-heart vines.

This seclusion and isolation ends during trips to the property’s restaurants and pools. The beachside pool and its tiered seating areas sit 40 feet from the water’s edge where live local musicians cover songs from island staples like Jimmy Buffet and Bob Marley. Its multiple bars and cabanas offer Bungalows-specific cocktails (like the Largo Lemonade) and small plate poolside snacks—the Baja fish tacos with a burst of citrus brightness were a treat. The pool overlooks the bay, where you can watch the Bungalows’ catamaran and guests enjoying rentable water activities.

Our first dinner was at the resort’s main restaurant, Fish Tales. The three-course meal offered a variety of options, from French peasant staples to expected island mainstays. The dinner menu is complete with a buffet-style dessert station, which, of course, contains Key lime treats. Dinner should be coordinated with sunset times as the dining room enjoys an unobstructed view of the sunset from appetizer to dessert. As the sun slips away behind Swash Keys, the array of colors seem to match our strawberry piña coladas and grapefruit margaritas.

The Bungalows other restaurant, Sea Señor, offers Mexican options from all over the country’s states. There are skirt steak entrées from the Norteño region and Oaxacan dishes like enchiladas, perhaps inspired by Key Largo’s early Spanish occupants.

The silver palm trees tower two dozen feet on both sides of any walkway. The wrought-iron bars that line the heated pool and Jacuzzi are impassible by sight or sound. It’s quiet—all of it. The sense of seclusion is immediate and tremendous. The tour, the map, the thousand lights attached to a thousand trees are there to provide a pathway in a property to make you feel like Robinson Crusoe on a hidden island, untouched and pure.