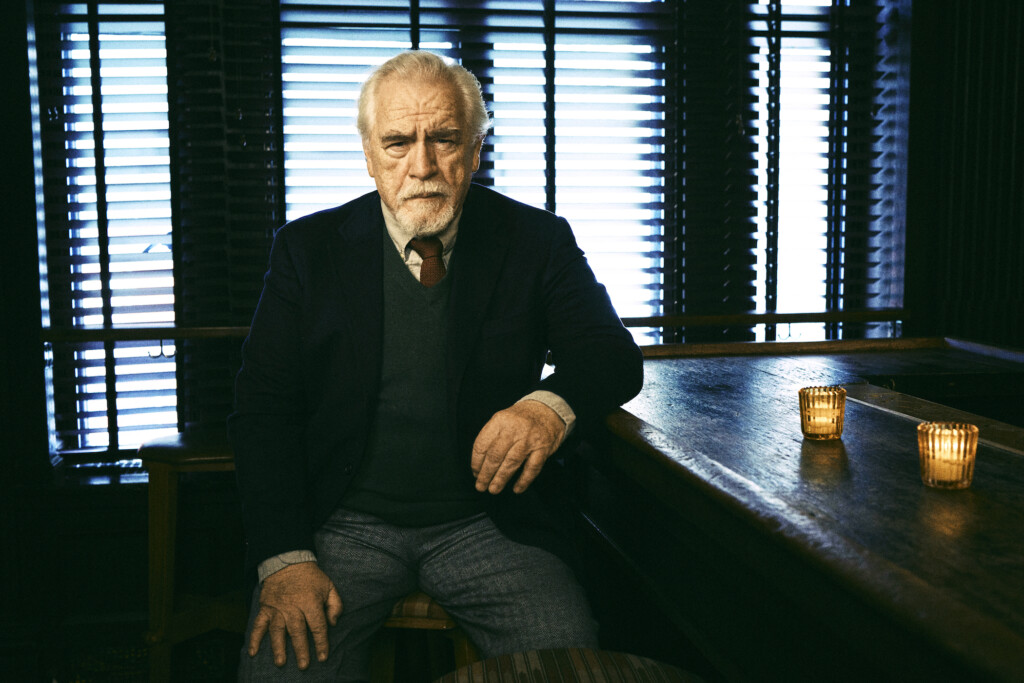

Brian Cox has been tasting the success in Succession. Thanks to the darkly satirical HBO series, in which he plays conglomerate-owning billionaire Logan Roy, Cox’s public profile has exploded like the finest champagne popping. “It’s a great role,” Cox tells me in his distinctive Scottish burr one recent morning. “An iconic character. A lot of people here see a lot of King Lear in the whole story.”

And the direct result of his playing the part with such authority and angst has been… celebrity! In his 70s (he’s 76 now), Brian Cox has become a bonafide superstar. “I used to pride myself on my anonymity,” he admits, “but it’s gone. Logan has taken over. I managed for 60-odd years to avoid that. Somebody once said, ‘It’s a long haul for you, Brian.’ I never knew it would be this long.” The seasoned actor lets out a hearty laugh of the type that Logan Roy rarely gets to enjoy.

The impact of Succession has been so strong that when Cox went to the London premiere of The Fabelmans last year, he became a reluctant object of frenzied paparazzi and fans. Cox went with a friend who had worked with Spielberg and who kept urging Cox to walk the red carpet, though the actor wasn’t sure it would be right, since he was only there as a plus-one. But he gamely did so, and all hell broke loose. “A photographer said, ‘Can you take your coat off so we can take some photographs?’” he relates. “The crowd went berserk. ‘Oh, Brian! Brian!’ I ended up signing about 100 autographs. I don’t want to be churlish because it’s wonderful and very touching and the public is always graceful and nice, but you’ve got to take it with a pinch of salt because it could all go away. At the same time, you can’t be graceless.”

Brian Cox’s life didn’t start with flashing cameras. He was born in Dundee, Scotland, to a mother who was a spinner in jute mills and a policeman dad who died when Brian was eight, leaving his mom distraught. She had suffered a series of miscarriages before Brian was born and, later on, she had several nervous breakdowns, leaving Brian, the youngest of five children, to be brought up by his three older sisters. At 15, he left school and gravitated towards the theater, working with the Dundee Repertory Theatre, then training at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. He made his West End debut in 1967 in As You Like It and gradually became one of the best-known interpreters of the Bard, spending seasons with both the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre throughout the ’80s and ’90s. An especially memorable project came in 1983, when he played the Duke of Burgundy in the Granada Television production of King Lear, starring Sir Laurence Olivier.

Having entered the world of television acting in Britain in 1965 when he was 19, Cox eventually expanded into movie roles. In 1986, he landed Michael Mann’s Manhunter, in which he was the first actor to play cannibalistic serial killer Hannibal Lecter (spelled “Lecktor” in that film). Manhunter got mixed reviews at the time, but it’s grown in status as a cult thriller rather than just a prelude to a phenomenon. As for Anthony Hopkins taking on the part in the classic The Silence of the Lambs, Cox jokes, “The only thing I didn’t like was he won an Oscar and made a lot of money!”

After Manhunter, Cox had to deal with a divorce from the actress Caroline Burt, whom he married in 1968 when he was just 21 and with whom he has two children, writer/director Margaret and actor Alan. By the mid-90s, Cox had situated himself in America to pursue other juicy opportunities. He figured this was a way to be in the heart of the entertainment industry, so he could suss out roles that appealed to him. Was it a relief to escape the British class system? “Yes,” he readily admits, “because America is known as an egalitarian state. But, as it turns out, that’s not really practiced.” Oh, well, it sounded great in theory.

Photo by TV Times/Getty ImagesFortunately, immersing himself in movieland allowed for some rewards. Cox got to pursue his gifts as a character actor — someone who dives into colorful opportunities, often in supporting, but scene-stealing, roles. “I think we all are character actors,” he says. “There’s the Brad Pitt syndrome, but in Babylon, the screen idol he plays is a character. I decided I was going to become a character actor. I don’t care about playing the leading man; I want to play a part that has quality. I owe it to a lot of my biggest influences — the character actors of the ’30s, like William Demarest. I thought, ‘That’s what I’ll do now.’” But in the process, he judiciously turned down some big movies, such as the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise (he felt the part in question — Governor Weatherby Swann — was pretty meh, especially in the shadow of Johnny Depp’s flamboyant Captain Jack Sparrow). And after working with Steven Seagal, he was hardly chomping at a chance for a reteaming. (In his forthright 2022 memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, Cox reveals that he found the ’90s action star to be on a different plane, but not necessarily a higher one. “It’s a shame,” Cox tells me, “because his politics are quite liberal.”)

Cox has learned not to regret having rejected various offers, especially since his Scottish grandma long ago told him something to the effect that if an opportunity gets away, then it wasn’t meant to be, whereas if you do end up doing something, then it’s yours. And the stuff he did choose was pretty choice, including key characters in films such as Braveheart (he was Argyle, the mentoring uncle of Mel Gibson’s Scottish warrior) and The Boxer (in which he played Emily Watson’s dad, an IRA leader fighting for peace). A special moment came in 2001, when Cox tackled a controversial role in the small but potent L.I.E. He brought all his dramatic skills to bear as Big John Harrigan, a pedophile who develops a complicated relationship with a troubled boy played by Paul Dano. “I was advised to think about it before taking it,” Cox reveals, “because of the subject matter. I said, ‘No, this is a really good script’ and ignored the advice. It proved to be a very good move on my part. I loved working with [director/cowriter] Michael Cuesta and Paul Dano, who was great, and I’m so happy with the way Paul has developed as a magnificent actor.”

Cox has worked nonstop since, but the stardust didn’t really fall until Succession premiered in 2018 to acclaim for its savvy look at jaundiced blood relatives lobbying for power at any cost. With the fourth and final season launching this month, the possible sale of Waystar Royco might continue to be a plotline, though Cox said he isn’t allowed to give any details as to what developments could lurk.

Told that he admirably doesn’t play Logan as a moustache-twirling villain, but as a human being, Cox — who’s won a Golden Globe and two Emmy nominations for his performance — has a response. “He is [human],” he says. “I have a lot of empathy for him. I don’t judge him. I think he’s had a troubled time. He’s a misanthrope and is also painting himself into a corner because of who he is. I think he’s a man who’s very disappointed in the human experiment, which has made him misanthropic, whereas I, on the other hand, am optimistic, even though it’s hard to be optimistic with the crises we find ourselves in, thanks to the political nonsense on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Does Cox think Logan has a favorite of his endlessly conniving offspring, or are they all vile to him? “He loves all his children,” insists the actor, “but he’s constantly been let down by them because they won’t step up to the plate, and it’s also the sense of entitlement. It’s funny because they have not been reliable. It’s been treachery and scheming. But of course, he’s created the whole thing. When you live at that level and have children, naturally they’re spoiled. They have a very, very narrow view of the world. They always talk about their ambition and what they want to do, and he gives them enough rope to hang themselves with.”

There’s no need for Cox himself to resort to such chicanery; his plate is running over these days, due in no small part to his HBO triumph. He’s set to star in four movies and two plays, one in London’s West End, just for starters. “I couldn’t ask for a better position,” he enthuses. “I also feel a need to go back to the theater before my mind finally goes. I’m nervous about it, but I’m going to do a play about Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederick the Great, and, in 2024, I’m going to do Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which is something I’ve always wanted to do.” He’s also directing and costarring in a film in Scotland this summer, Glenrothan, about two estranged, reuniting brothers and the family distillery. Maybe it’ll be Succession with a thicker brogue.

The picture that emerges of Brian Cox is one of a modest yet forthright person who’s been served a surprising new career chapter that he’s tickled by, though he’s deep down still the hardworking Shakespearean actor of days past.

And he seems to have achieved a gratifying balance in his relationship with his wife, German-born actor/director Nicole Ansari, who is 54. The couple, who married in 2002, lived in a penthouse in a Downtown Brooklyn high-rise for ten years, but moved to a house not far away, in Boerum Hill. “We adore this neighborhood,” Nicole tells me, “and our life revolves around the span of five blocks. We try to avoid crossing the bridge into Manhattan. That frantic city energy can be inspiring, but tiring. Brian misses London a lot, so being in a house — and a neighborhood with houses, not skyscrapers — makes him feel more at home.”

Photo by Emma McIntyre/Getty ImagesTheir life together? “Because of our jobs,” she explains, “we rarely get to spend time together at home, so when we are home, we like to lounge and do nothing much other than watch TCM together, have dinner with our boys, and walk over to one of our neighborhood cafés for breakfast. Home becomes a special kind of vacation for us.”

The “boys” are Orson, 21, who’s studying acting, and Torin, 18, who’s applying to colleges. They live on the third floor of the house, “and have their own world up there,” says Nicole. “I love that they are still living with us. The house would feel too big and empty without them.”

In another sane move, Brian and Nicole happen to sleep in separate bedrooms. “I think it is the best decision we ever made,” says Nicole. “Of course, this is not possible for every couple. But I think it is so important to have your individual space. Instead of having an office, each can have their desk in their own bedroom. I think a lot of couples actually suffer from overexposure to each other. No wonder they get bored! We both also like our own company. We are OK with who we are and don’t need the other to validate us. It also helps having time apart and discovering each other after travels.”

Brian agrees that some separation time is good for the relationship. He says their secret as a couple is “allowing each other to be who they are and not trying to make them who they’re not. Total respect for their position and what they want to do. And actively encouraging. Nicole is very smart — a great director and with terrific visual sense. And she’s gotten me into being an activist. She’s doing a lot of work for women in the Middle East.”

By the way, Brian met Nicole in 1990 when he was playing… King Lear.