In June of 2017, as the first Cosby trial was taking place, and the seemingly never-ending parade of what novelist Jenny Offill has called “art monsters” were being marched through the public square, Seattle’s belle-lettrist Claire Dederer started keeping a list: Polanski, Allen, Cosby, Galliano, Mailer, Wagner, Caravaggio… She wished someone would invent a calculator. You would insert the name of an artist, and the calculator would measure the heinousness of their crime, balance it against the greatness of the work, and spit out a verdict: you could or could not consume their work with an easy conscience.

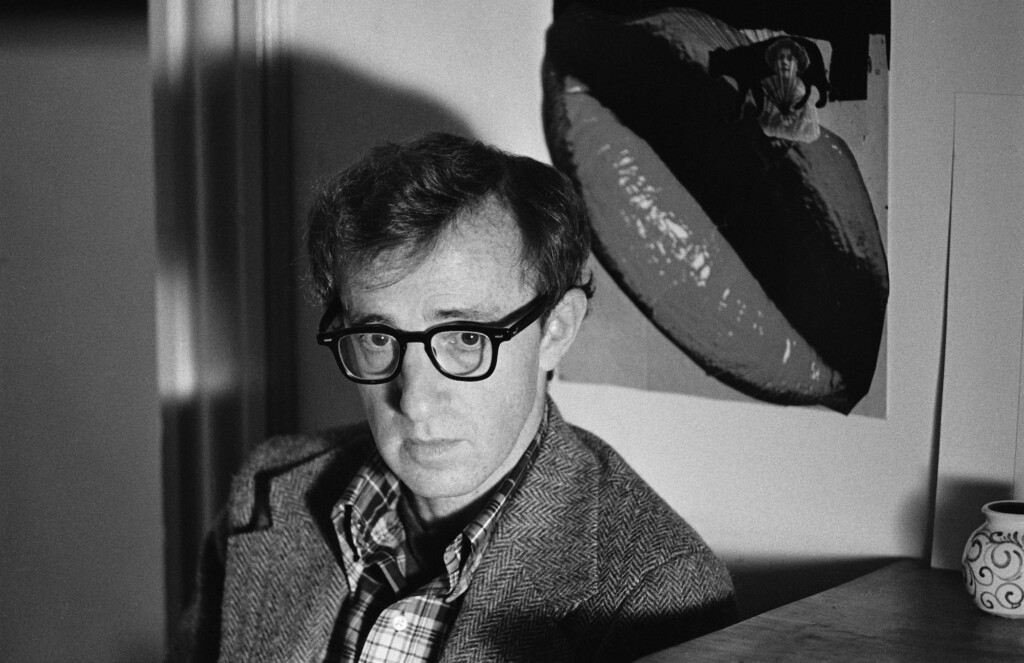

She spent much of the Trump years rewatching Polanski and Woody Allen movies, trying to figure out the calculus herself. She rewatched Manhattan, whose masterpiece status she had once endorsed but now found woefully unalert to the moral complexities of its central theme: middle-aged men nailing high schoolers. “Allen is fascinated by moral shading except when it comes to this particular issue,” she writes in her thrillingly smart new memoir Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma (Knopf ). “In the face of this particular issue, one of our greatest observers of contemporary ethics — someone whose mid-career work can approach the Flaubertian — suddenly becomes a dummy.” But, after on-demanding Annie Hall, she fell in love all over again, and felt “almost mugged by the sense of belonging. I don’t go around feeling connected to humanity all the time. It’s a rare pleasure. And I was supposed to give it up just because Woody Allen behaved like a terrible person? It hardly seemed fair.”

What was she supposed to do? Junk Manhattan but keep Annie Hall? Watch them, but only at a friend’s house? We’ve all faced versions of this dilemma over the last few years — what ought we to do with great art by bad men — but Dederer, whose previous books are Poser: My Life in Twenty-Three Yoga Poses and Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning, has skin, heart, and brains in the game. Growing up in Seattle in the late ’70s and early ’80s, she experienced her first sexual assault at 13, two attempted rapes, multiple assaults on the street, and innumerable gropings — not far off the norm — all the while poring over Life magazine spreads of Picasso and Hemingway, those avatars of male genius, “muscular, unfettered, womanizing, virile, cruel, sexual.” Years later, taking her own daughters to the exhibition Picasso: The Artist and His Muses at the Vancouver Art Gallery, as they learned how he destroyed each woman in turn, her daughters recoiled. “Ugh, this is so depressing,” one of them said, finally. “What a disgusting creep. Can we leave?”

All these things can be true at once. The masterstroke of Dederer’s book is that she doesn’t seek to duck her ambivalence. She doesn’t try to magic it away by finding an expert or thinking harder, although her book has crystalline intellectual force, and still less by pointing fingers, although her command of the demotic is delicious (“I took the f***ing of Soon-Yi as a terrible betrayal of me personally,” she writes). Denounce Allen or Polanski all she wants, she realizes, their work still calls to her, and from that stubborn fact she has fashioned a book of depth and candor about what it is to be heartbroken by an artist whose work we also happen to love. “Love is the quiet voice,” she writes, “next to the louder call for public shaming.” You might call it a manifesto for un-cancel culture. The love doesn’t cancel out the horror, nor does the horror cancel out the love. They simply sit side by side, as they do in our heads, shimmering like swathes of color in a Rothko.

So on point is Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma about the historical moment in which we currently find ourselves, you want to carry it around with you and whip it out at every bar or dinner party where people are getting heated about Louis C.K., say, or Kevin Spacey. What would Dederer’s hypothetical moral calculator make, for instance, of a stinker like Roald Dahl — notoriously anti-Semitic, offensively opinionated, bullying, overbearing, and “an absolute sod,” according to critic Kathryn Hughes? Even his three-year-old son called Dahl a “wasp’s nest.” In Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected (Pegasus), the acclaimed biographer Matthew Dennison brushes off the wasps to deliver a brisk thumbnail sketch that doesn’t supplant so much as supplement Jeremy Treglown’s definitive, thornier 1993 biography of a writer, whose assholeness, like Picasso’s, was in some sense baked into the cake.

Photo courtesy of Pegasus BooksGrowing up fatherless in South Wales, exiled to a boarding school where he was “caned for doing everything that it was natural for small boys to do,” Dahl later lost his youngest daughter to measles, and nursed his first wife, actress Patricia Neal, back to health after a stroke, noting down her nonsense phrases for use in his children’s books about orphaned survivors — James and the Giant Peach, The BFG, Matilda — in which the cruelty, wickedness, and violence are laid on with gusto. “Life isn’t beautiful and sentimental and clear,” Dahl once wrote. “It’s full of foul things and horrid people.” That children feel this as much as adults, if not more so, is maybe one of the reasons Dahl’s books have sold over 250 million copies in 58 languages.

There are enough foul things and horrid people in James B. Stewart’s and Rachel Abrams’s Unscripted: The Epic Battle for a Media Empire and the Redstone Family Legacy (Penguin Press) to have had Dahl levitating with delight. First is Sumner Redstone, the waxen-skinned Methuselah who sat atop the Viacom empire, whose geriatric hobbies included harassing women on planes and choking on his steak when it wasn’t cut into small enough pieces. Then there are his two live-in girlfriends, who moved into Redstone’s mansion, cut off communication with his family, and started siphoning off his millions: Manuela Herzer, a naturalized Argentinian dodging angry creditors and a restraining order; and Sydney Holland, a recovering alcoholic trailing a string of liens, court judgements, and a failed yoga apparel line. She also boasted a boyfriend named George Pilgrim, who once made a “Hunks in Trunks” photo spread for Men; got caught impersonating the grandson of William Randolph Hearst for a VH1 reality show, Hopelessly Rich; and whose Facebook approach to Sydney was, “I think you’re hot. Damn, I’m hung.”

With a cast as good as this — Weekend at Bernie’s as rewritten by James M. Cain — it makes perfect sense that Stewart and Abrams, who originally reported on the story for the New York Times, would divide their book into “seasons” and “episodes” like a CBS reality show. They’ve written the literary equivalent of a guilty binge-watch, whose eye-widening excess is matched only by the feeling of pleasurable superiority one feels while surveying the moral tawdriness of the mega-rich. And that’s before we’ve even got to the season finale: the slow tick-tock of accusations against CBS’s Les Moonves, in the wake of the Weinstein scandal. The most poignant chapter is the closing one, which does a “Where Are They Now?” for the entire cast of liggers and scammers. Herzer is refused a bank account by First Republic Bank. Pilgrim is still looking for a publisher for his autobiography, Citizen Pilgrim, while obeying the terms of a restraining order brought by Holland, who auditioned for The Real Housewives of Beverley Hills before getting her claws into a rich, elderly doctor in San Diego. It’s like seeing lizards scamper off into the desert to find another rock.

One of the more interesting points made by Michael Schulman in his ambitious Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat, and Tears (Harper) is that the Academy Awards were designed, in part, to deflect from exactly this kind of scandal. After the mysterious death of Olive Thomas, a former Ziegfeld girl, who ingested poison in the bathroom of the Paris Ritz; Virginia Rappe, the silent film actress found mortally injured in the hotel room of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle; and the tragic end of morphine-addicted actor Wallace Reid, stars discovered “morality clauses” written into their contracts, to prove that Hollywood was no latter-day Gomorrah of addicts, orgiasts, and harlots. MGM’s owner, Louis B. Mayer, had an even better idea and proposed the formation of an Academy — the loftiness of the title provoked much eye-rolling — along with an annual gong show, in order to keep the talent in line. “I found that the best way to handle [artists] was to hang medals all over them,” said Mayer.

If Mayer is one of the book’s more colorful villains — “You are talking about the devil incarnate,” said actress Helen Hayes. “Not just evil, but the most evil man I have ever dealt with in my life” — the bashful hero of the book turns out to be Gregory Peck, whose transformative tenure as Academy president from 1967–70 invigorated membership with a younger generation, including Dennis Hopper, Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, and Elliott Gould — whose ingratitude makes you wince. “I would rather have a good three-man basketball game than sit there in my monkey suit,” quipped Gould. At the 1970 awards, Jane Fonda turned up in her Klute shag and pumped a fist — “Right on!” — while protestors waved “JOHN WAYNE IS A RACIST” placards. “This is not an Academy Awards, this is a freakout,” joked host Bob Hope, nervously.

Photo by Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty ImagesFamously, the right-on kids of the Easy Rider generation pushed the X-rated Midnight Cowboy to a best-picture win, but the ironic coda to the story comes 46 years later, when many of those same groovy kids, their ponytails now graying, found they were the ones being put out to pasture by Academy president Cheryl Boone Isaacs, following the public shame-a-thon of #OscarsSoWhite in 2016. What goes around comes around. In the wake of the Weinstein scandal, a new “code of conduct” clause was also introduced into the Academy’s rule book, echoing the “morality clauses” of the ’20s. Sometimes, the two-step between monsters and their accusers feels like the oldest dance number in town.