There we were thinking of Merchant Ivory as the avatars of starchy propriety, making films as decorously well-behaved as a governess, clutching their inhibitions like pearls. And then along comes James Ivory with a poignant, unbuttoned memoir of his life and career that reads like one long roll in the grass.

“If you can go back to a film like Shakespeare Wallah, there’s a couple in bed and they’re necking all the time, and that was my second film,” says the 93-year-old director on the phone from his 19th-century mansion in New York’s Hudson Valley when I confess his book made me blush. “Or you go to Bombay Talkie, there’s another one. There’s lots of sex in that. Or think about Maurice. They repressed their emotions, definitely in The Remains of the Day, of course they did. But in Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, when Mr. Bridge is looking out the window and he sees his daughter putting on suntan lotion down below through the window, and this obviously excites him. And at that moment, Mrs. Bridge comes into the room and he grabs her and pushes her down. What is that?

“There were three very sexy people making these films all along,” he continues, referring to himself, producer Ismail Merchant, and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. “Ismail was a highly sexed man, and it wouldn’t be right to go into Ruth’s sexuality. She was certainly very much aware of sex, and I have always been a sexual person. So it’s always going to come out in the movies.”

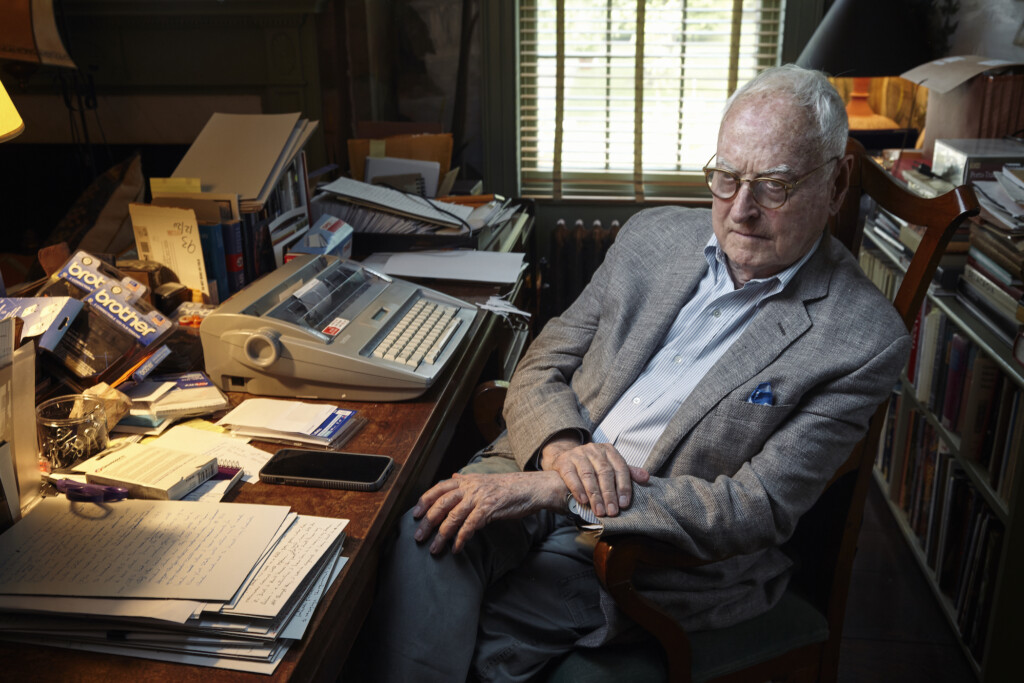

His forthcoming memoir, Solid Ivory, is a loose-leaf album of reminiscences, inset with some beautifully observant thumbnail portraits of Ivory’s close friends, lovers, and collaborators over a nearly 50-year career. Here is Daniel Day-Lewis on the set of A Room With a View with too-long fingernails which Ivory dared not ask the actor (famous for his immersion in roles) to cut for fear it would break his concentration: “It’s better to have long nails and wonderful performances.” Here are Raquel Welch and Vanessa Redgrave in The Wild Party and The Bostonians respectively, prompting thoughts on “the intense relationship, tinged with lunacy, that a film shoot forges between director and star.” Here is Hugh Grant, quipping of the stingy pay he got for Maurice: “I did it for the curry.” (Ismail cooked a mean rogan josh.) And above all, here are Ismail Merchant, the restless, energetic dynamo from Bombay who was also Ivory’s partner until his death in 2005; novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, private and preternaturally observant; and Ivory himself, relaxed, easygoing, and comfort-seeking in his Brooks Brothers seersucker jacket. “I do feel we were a little bit like aliens in a way — from outer space,” he writes of the Merchant Ivory “brand,” as distinctive amid the dust-ups and din of ’80s and ’90s cinema as the hood ornament on a Rolls-Royce.

Photo by Ronald Grant/Alamy Stock Photos“You feel like an alien, particularly when you mingle in Hollywood. Less so in England, you could be more weird in England and get away with it,” says Ivory, whose blend of refinement and outsiderishness can be traced to his upbringing in Klamath Falls, Oregon, where his father built a successful lumber business during the Great Depression. It was a life of highballs, limousines, and foxtrots beneath the dome glass and crystal chandeliers of San Francisco’s Palace hotel at Christmas, which acquired a dreamlike texture with the news, received at aged 10, that James was adopted. He began collecting cased daguerreotypes, assembling “a group of virtual ancestors. I preferred family groups of well-dressed people — pretty girls with lively, intelligent faces… and handsome waist-coated young gentlemen in stiff collars.”

His adaptations of E. M. Forster and Henry James would do the same. A similar cinematic echo can be detected of Ivory’s sexual awakening as a teenager during a time when homosexuality was criminalized in the United States. “That sort of thing, while imaginable in fantasies, was indeed unspeakable,” he writes, poignantly, and you can’t help but wonder how much that radar for the unspoken has enhanced Ivory’s dramas. Anthony Hopkins’s awkward conversation with Lord Darlington’s godson (Hugh Grant) about “the birds and the bees” in The Remains of the Day echoes a similarly stilted chat Ivory’s father had with his son about circumcision.

“So much drama is what was not spoken of suddenly coming out in an explosion,” he tells me. “My father really couldn’t talk about emotions. I mean sex, never. I learned about sex from my mother. My father never gave me one scrap of information. You couldn’t talk to my father about emotions of any kind without him tearing up. Today, of course, we’re all over the place, aren’t we? But that’s good. Thank God.” Did his father know that his son was gay? “I think my father must have probably, because he made a trip in Europe with Ismail and me. We were all traveling together and it was not upsetting to my father that we were, and he liked Ismail very much. And at one point even he even said something like, ‘Well, when I’m gone, at least you have Ismail to take care of you.’”

Photo from the collection of James Ivory, courtesy of Farrar, Straus and GirouxIn fact, tragically, Merchant died of a hemorrhaged ulcer in 2005 at the age of 68, while the pair were shooting The White Countess. “It was a terrific shock,” Ivory says. “I had the feeling, though, that as we went on, we might not have made that many more films. I feel that he was beginning to feel, ‘Well, I’ve had enough now.’ ”

Ivory still spends each August at a 650-square-foot Oregon cabin his parents bought when he was a boy. The 19-room mansion in the Hudson Valley, which he bought in 1975, in whose tiny kitchen Merchant once cooked his famous lamb curry, on whose lawn actors like Helena Bonham Carter and Gwyneth Paltrow picnicked, and where Vanessa Redgrave once gave readings of Chekhov, is home to a collection of objets, heirlooms, and antiques rescued from various film sets over the years, although he regrets having sold an 18th-century figure of the winged Hindu deity Garuda, an acquisition of Merchant’s, as part of a sale through Christie’s in 2009. “If I could find out where it went, I would try to buy it back,” he writes.

These days he is friends with a young generation of filmmakers like Wes Anderson, who used a couple of pieces of music from Ivory’s Indian films in The Darjeeling Limited, and Luca Guadagnino, who supplied Ivory’s career with its coda in the form of 2017’s coming-of-age film, Call Me By Your Name, starring Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer. Ivory scripted and won an Academy Award for the film, at age 89, making him the oldest Oscar-winner ever, even as the film drew criticism in some quarters for Guadagnino’s cutaways to trees during the sex scene. Ivory’s script was more explicit. “The irony is that both Luca and I have had a lot of male frontal nudity in our films,” he says. “Think of A Room with a View or Maurice or Quartet. But the actors wouldn’t do it. American actors just don’t like doing that, whereas in Europe, they’re happy to throw off all their clothes and run around, that’s fine. But that’s not true in this country. It didn’t exactly mess up the film, but I thought when you had two directors who never shied away from that in the past now being told you couldn’t do it by the actors, that’s the irony.”

But even if young Hollywood isn’t always keen to strip down for art, the birds and the bees can still be visited in James Ivory’s garden — and now also his book.

Solid Ivory: A Memoir, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is available online and in stores now.