When I was trying to conceive more than eight years ago, I became familiar with the drab, factorylike waiting rooms of fertility clinics. They often contained rows of women biding their time before appointments in a windowless, cramped space devoid of amenities, with beige tones everywhere to be seen.

But on a recent visit to CCRM, on the 21st floor of a modern midtown Manhattan building, I was in a light-filled, airy setting with gleaming white floors and walls and views of the city sky-line. I listened to a catchy playlist with Coldplay songs and could choose from refreshments like flavored sparkling waters, Luna bars, and Skinny-Pop popcorn.

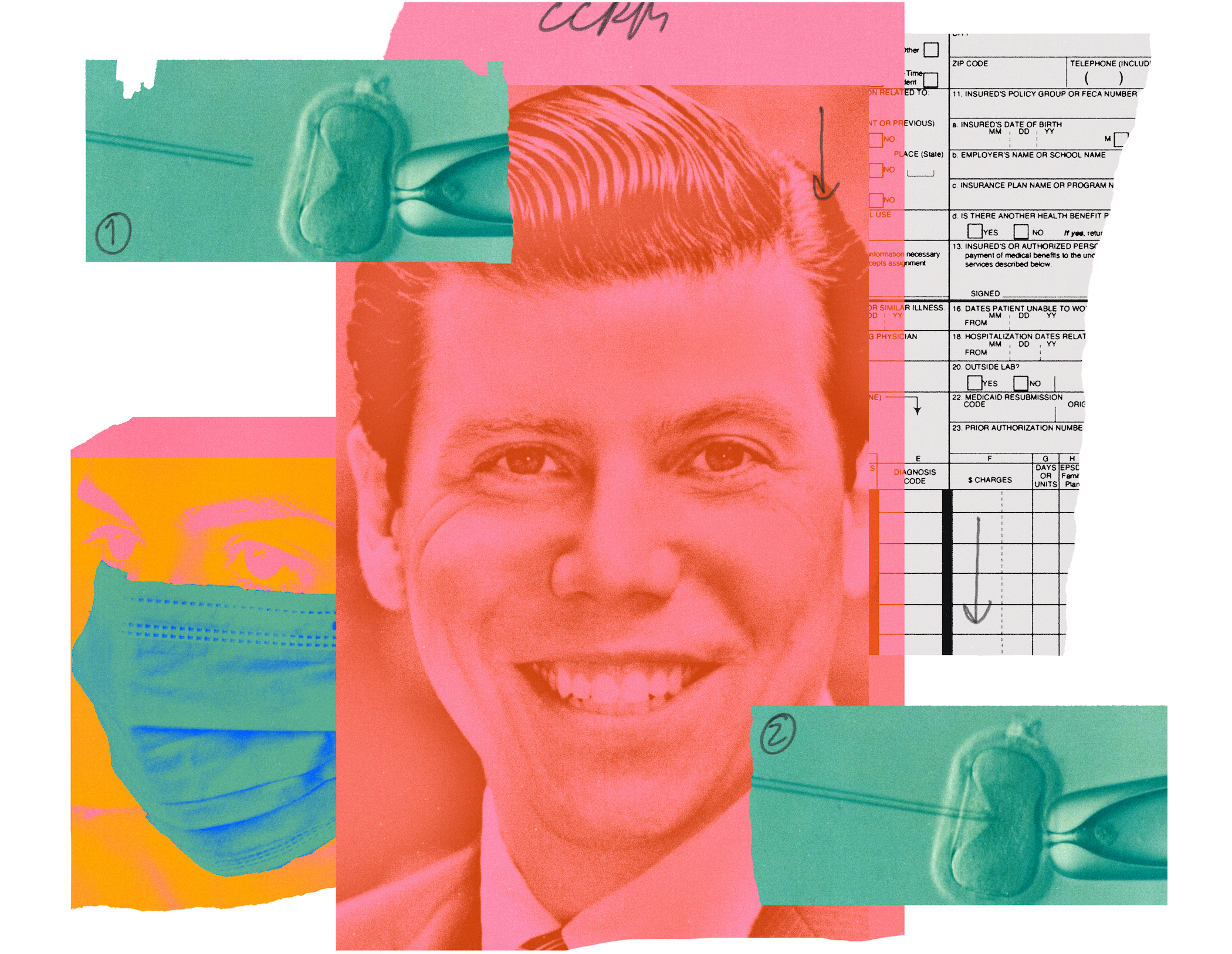

I was there to interview Dr. Brian Levine, the founding partner and practice director, who is board-certified in reproductive endocrinology and infertility as well as obstetrics and gynecology. Since setting up his practice in 2015, CCRM, based in Denver, has earned a reputation of being among the leading New York fertility clinics.

In the wake of COVID-19, fertility specialists are more sought after than ever. Birth rates in the United States have declined for five years in a row: according to the Vital Statistics Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the provisional number of births in 2019 was 3.74 million, the lowest since 1985.

Any woman like me who has struggled with infertility knows that the process of trying to get pregnant is fraught with anxiety. Fertility treatments, especially pricey IVF, is practically a full-time job and strains the best of relationships, not to mention finances — and that’s when circumstances are normal. The current global pandemic has created an unprecedented urgency for fertility services.

“Dealing with COVID-19 on top of an already difficult situation of infertility compounds the unknowns,” says Barb Collura, the president and CEO of RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, a nonprofit patient advocacy group. “People are afraid and have questions that are hard to answer. If they get pregnant and test positive for COVID-19, for example, can they pass the virus onto their unborn child?”

Dr. Levine, 40, is more direct. “The pandemic has thrown people into a reproductive panic,” he says.

Many women are turning to IVF without first trying to conceive on their own.

“They don’t meet the definition of infertility, but they want to get pregnant now,” he says. “I’ve had several patients who are moving out of New York because of the virus and want to conceive before leaving the city because they think that the best fertility care is here.”

Other new patients, says Dr. Levine, are unsure how the virus will play out and are preparing for a later pregnancy by undergoing IVF and freezing their eggs, or harvesting embryos.

Illustration by Ricardo SantosA third camp is concerned about job security and wants to take advantage of a New York State law that mandates companies with more than 100 employees must cover three cycles of IVF treatment.

“People are telling me that they think they’re going to lose their jobs and want to use their benefits while they still have them,” says Dr. Levine.

COVID-19 may have accelerated his clients’ desire to get pregnant or protect their future chances, but Dr. Levine says that a major difference among his patients today compared with ten years ago is that they don’t want twins.

“There was a time going back to the ’90s when it seemed like every woman in New York was giving birth to twins,” he says. “People today don’t want the expenses that come with raising two kids or the complications of a pregnancy with twins. Ninety-five percent of the transfers we do at CCRM are of single embryos.”

This statistic fits into the larger trend of childbirth in the United States. According to the Practice Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, in 2000, more than two-thirds of all IVF transfer procedures in the United States were of three or more embryos, but between 1999 and 2008, this number dropped from 70% to 39%.

New IVF cycles, along with all other fertility treatments, halted during the lockdown, but when CCRM restarted them in late April, Dr. Levine saw a surge of new patients.

“We did 100 IVF cycles in May, compared with 75 last May, and could have done many more without social distancing protocols,” he says.

Beyond the doors of the waiting room, Dr. Levine and his three other equal partners, all women, have stylish offices. The exams rooms are bright and spotless, while the typically sterile operating rooms, where women undergo embryo transfers, resemble private hospital suites with comfortable beds.

An acupuncturist is on hand for sessions immediately before and after transfers, as well as during ongoing treatment. In the post-transfer recovery room, there’s another upbeat playlist and more snacks.

Amenities aside, CCRM has serious medical chops: the clinic is a pioneer in that it does all genetic testing on embryos onsite, instead of using an outside company. It is also a leader in frozen embryo transfers and complicated cases, such as when a woman has recurring miscarriages.

Chromosomal abnormalities are one of the biggest reasons why women miscarry. To reduce the chances of a loss, the original CCRM in Denver began freezing embryos instead of doing fresh transfers. These embryos were then tested for genetic abnormalities and transferred only if the results indicated that none existed.

This may be standard practice among fertility clinics today, but when Dr. Levine partnered with CCRM, the office was at the forefront of treatments. He says that is the reason why his practice has low miscarriage rates of around four to five percent.

Elite medical facilities like CCRM typically don’t accept insurance and tend to have high price tags, but Dr. Levine insists that his is more democratic. Although the practice only accepts Progyny, an insurance for fertility benefits that many employers don’t offer, he says that no patient is turned away.

“We find a way to work with you,” he says.

Paying out of pocket, while not inexpensive, isn’t catastrophic: a 90-minute consultation with Dr. Levine or one of his partners is $600, and a typical IVF cycle costs $25,000: definitely not the priciest in town.

Dr. Levine’s patients praise his personable bedside manner and accessibility, which includes his cell phone number.

“I’d much rather you ask me than google something and make yourself worried,” he says.

Valerie Katsorhis had two children via IVF with Dr. Levine — one using her eggs and another using eggs from her wife, Tyler. “I had an awful experience at a previous clinic where the procedures happened in the basement of a brownstone,” she says. “Dr. Levine turned a nightmare into my dreams come true. Every time I went to see him, I felt like I was going to see an old friend, not a doctor. I looked forward to the visits.”

I was also charmed by his manner. We discussed our mutual love of long hikes and mezcal, and our shared 4:30 a.m. wake-up time. “I try to treat every patient like I treat my wife,” he says. “My dad died of pancreatic cancer, and doctors would always talk at us. I want to talk to you.”

Dr. Levine’s personal brush with pregnancy loss is another factor behind his empathetic personality. Prior to giving birth to their daughter, Izabel, 3, his wife, Alexis, a former merchandiser for Ralph Lauren, had an ectopic pregnancy that resulted in miscarriage.

“That was hard, but we’re so grateful for Izabel. She’s the love of my life,” he says. “I know firsthand what it means to have a healthy child.”