It was a scene out of a Hollywood movie. On a raw March day in New York City in 1992, 71-year-old Leona Helmsley was admitted to New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, the very hospital to which her family had donated the Helmsley Medical Tower just years prior. Earlier that day, having been convicted of evading $1.7 million in taxes, a federal judge sentenced her to four years in prison plus 750 hours of community service, and ordered her to pay a $7.1 million tax-fraud fine. Hours after hearing the news, the self-made billionaire collapsed. Her heart was literally giving out. Just months prior, she had confessed to the gossip columnist Cindy Adams in a rare, televised interview that the stress of the lawsuit was taking a toll. “I cry a lot,” said Helmsley.

Hers had been a swift rise, advancing from humble beginnings to become one of the wealthiest women in the world. It was an even swifter descent, creating enemies left and right along the way, eventually earning herself the iconic nickname “Queen of Mean.” But ultimately — despite the society gossip, the press frenzy, the lavish displays of ’80s wealth and excess — who was Leona Helmsley?

Born Lena Mindy Rosenthal to Polish-Jewish immigrant parents in Ulster County, New York, in 1920, she changed her name several times as a young woman before landing on Leona Roberts. She changed husbands several times, too, before finding one that suited her. At 18, having relocated to New York City, she married attorney Leo Panzirer, with whom she had one son, Jay. Leona divorced Panzirer, then went on to twice marry and twice divorce a garment industry executive, Joseph Lubin. By 1960, Leona found herself a thrice-divorced single mother — and the only way to go was up. She eventually gravitated towards that quintessential New York career that can make or break fortunes overnight: real estate.

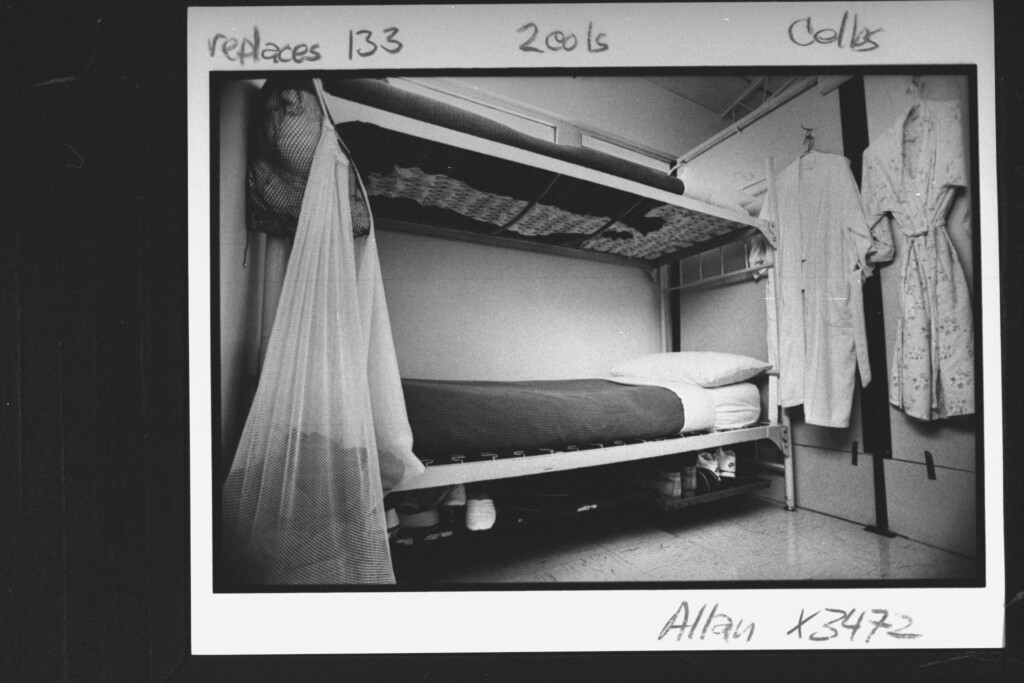

Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty ImagesLeona specialized in Upper East Side condos in a period of rapid gentrification for the city when new money was pouring in, turning swathes of rental buildings into condominiums. By the end of the ’60s, she was a self-made millionaire in her own right — and was able to catch the eye of Harry Helmsley, who was a veritable real estate legend of the era, managing some of Manhattan’s top commercial properties, including the Empire State Building.

In 1972, having divorced his wife of 33 years, the way was cleared for Harry and Leona to marry, becoming one of the wealthiest and most talked-about couples in New York society. Their romance was not without its hitches, however. Leona had encountered her first real spat of drama in 1971, when several of her tenants sued her for forcing them to buy condominiums. As part of the judgment, her real estate license was suspended. But luckily for Leona, her marriage to Harry arrived at just the right time: she joined Harry’s company as an executive and began working on his growing hotel business.

In 1981, the defining tragedy of her life occurred, one which would haunt her for decades and which ultimately cemented her legacy as the “Queen of Mean.” Her only son, Jay, passed away from a heart attack at the age of 42. Jay’s widow and child, who lived in a property that Helmsley’s business owned, were evicted soon after his funeral, for reasons that remain unclear. Helmsley also sued her son’s estate for money she alleged was a loan, and a court awarded her almost $150,000 after years of litigation. With no son to live for, and a troubled relationship with his widow and heirs, there was nothing left for Leona to love except her husband, her career — and her money.

By the end of the ’80s, Leona Helmsley oversaw about 30 hotels, including the Park Lane Hotel and the Helmsley Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue (today the Lotte New York Palace). She appeared in advertising campaigns for the hotels, posing tongue-in-cheek as a queen, sometimes wearing tiaras. But with this corporate success, a public fascination followed, and so did a miserly reputation. Leona became known for firing staff on the spot if beds were not made properly or lampshades were crooked, and for creating what, by any modern measure, would be called a hostile work environment.

Photo by Jimlop Collection/AlamyRumors of her tax avoidance began to swirl. A number of contractors and vendors during this period claimed that the Helmsleys often paid invoices late, if they paid them at all. Leona allegedly ordered a jeweler to rewrite a bill to save herself four dollars in sales tax, and would often purchase jewelry in New York City and carry the baubles home, only to have empty jewelry boxes shipped to an address in Florida to ostensibly avoid sales tax. During this period she famously told a housekeeper, “We don’t pay taxes; only the little people pay taxes.”

In 1988, then U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Rudy Giuliani indicted Leona and Harry Helmsley for illegally evading $4 million in taxes, in a scheme that included billing renovations of their personal home in Connecticut to the hotel business, and using furniture purchased through the business for their homes. By the time the trial concluded, and she was sentenced four years later, her legacy as the stingy “Queen of Mean” had been cemented forever. Leona Helmsley served 21 months, 18 of which were spent in federal prison.

After her release, she drifted into isolation and obscurity, estranged from most of her family and with very few friends. When Harry died in 1997, he left his entire $5 billion estate to her. As New York does not allow convicted felons to hold liquor licenses, she was forced to give up control of the Helmsley hotels empire, and she spent her final years largely alone with her dog in a penthouse atop the Park Lane Hotel. There were still the odd incidents here and there — such as in 2002, when a former employee sued Helmsley for firing him solely because he was gay. A jury sided with the former employee, and a judge ruled that Helmsley pay him over $500,000 in damages. Eventually, Leona Helmsley passed away from congestive heart failure at the age of 87 in 2007.

Although the “Queen of Mean” lived a melodramatic life of dizzying highs and heart-wrenching lows, the final years of her life were marked by enormous charitable donations which suggest a sort of penance: she donated $5 million to help the families of New York City firefighters and police after September 11th; she left $25 million to NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital for medical research; and she famously established a $12 million trust fund for the care of her beloved Maltese, Trouble. But even in death, Leona made it clear that crossing her had painful consequences, both emotional and financial. For reasons that still are not widely known today, the billionairess left nothing to two of her four grandchildren, nor anything to her estranged daughter-in-law. Her remaining two grandchildren received cash gifts of $5 million each — and that’s still less than the dog got.