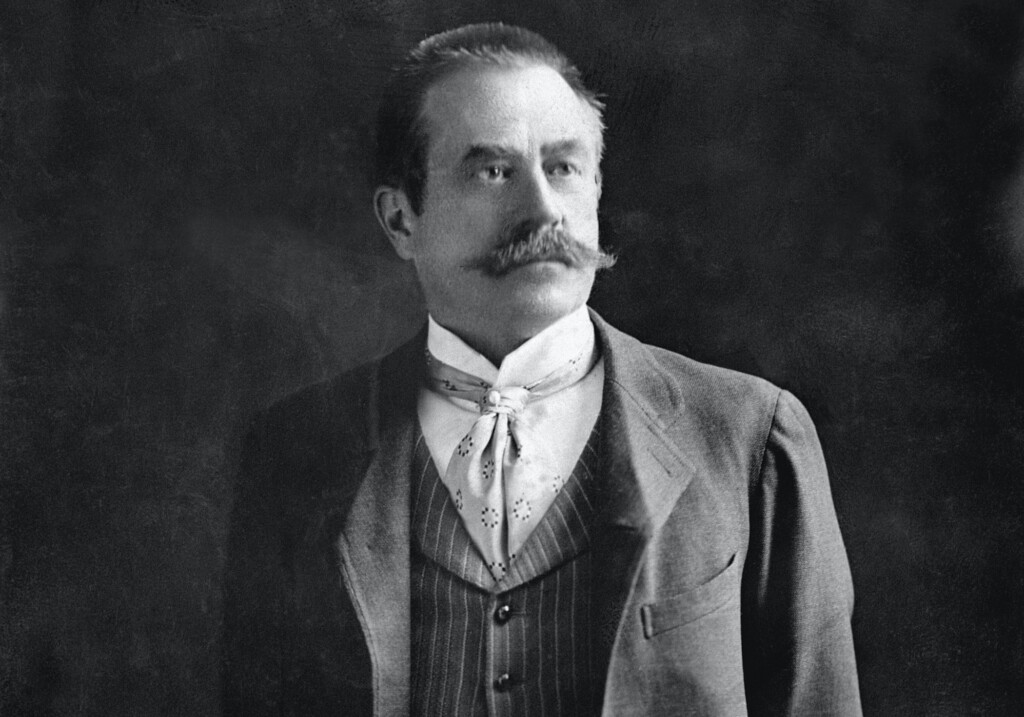

During New York’s Gilded Age 120 years ago, Stanford White was the most famous architect in the city. His clients and friends were among the era’s elite, and many edifices raised under the banner of his firm, McKim, Mead & White, are still recognized as masterpieces of American architecture.

He was also a sexual predator who was murdered in public by the husband of one of his victims, during a musical theater performance at one of White’s own buildings, an earlier iteration of Madison Square Garden. In any ranking of New York society scandals, the White affair is quite possibly the all-time number one.

“In his oeuvre, his appearance, and in his tabloid-worthy personal life, Stanny White projected color, and lots of it,” says architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson, author of McKim, Mead & White Architects, a landmark volume on the firm. Commissions for White’s robber baron clientele included a Madison Avenue mansion for J. P. Morgan (now the Morgan Library), and the Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park.

“White loved to create theatrical buildings with lavish ornament and interiors where important events could cause commotion,” Wilson tells Avenue. Between 1879 and 1915, his firm designed more than 900 of these — hotels, private clubs, libraries, museums, universities, churches, and even casinos.

On the evening of June 26, 1906, the architect was gunned down in the open-air rooftop theater of the Beaux Arts Madison Square Garden. (Demolished in 1925, it was the second of three Manhattan arenas to bear that name, and precursor to the current venue.) The killer was Harry Kendall Thaw, a Pittsburgh millionaire with a history of mental illness, who had never forgiven White for raping his new bride, showgirl Evelyn Nesbit, five years earlier, when she was just 16.

Photo by Gertrude Käsebier/Library of CongressThe night of the murder, White had been supping at nearby Martin’s restaurant, where he was spotted by fellow diners Thaw and Nesbit, who were also enjoying a meal before the premiere of Mam’zelle Champagne atop the Garden. During the show’s final number, “I Could Love a Million Girls,” Thaw approached White with a pistol and fired three shots at point-blank range, hitting White twice in the face and once in the left shoulder, killing the 52-year-old architect instantly. Standing over the body, according to contemporaneous press reports, Thaw said: “I killed him because he ruined my wife.”

White had concealed his sexual predation behind the veneer of being a “respectably” married man. In 1884 he had wed 22-year-old Elizabeth “Bessie” Springs Smith, a descendant of the founder of Smithtown on Long Island’s north shore. In neighboring St. James, he would design Box Hill, a 20-acre summer retreat that served as a showplace for his grand aesthetic, and remains in the family today.

Following a lavish wedding, the Whites took a six-month honeymoon in Europe and the Near East, purchasing copious antiques and architectural fragments for their own and clients’ collections. “Once back in New York,” says Wilson, White became quite the sensation “with his loud clothes, red hair and moustache, and ebullient personality…[and he] soon found the attractions of money and flesh were irresistible.”

Photo by Bettmann/Getty ImagesHis appetite was for young girls, grooming many in his multistory Manhattan apartment with a rear entrance on 24th Street. There, he had a room painted green and outfitted with a red velvet swing suspended from the ceiling by ivy-twined ropes. According to Simon Baatz, author of the 2018 book The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century, the architect “was one of a group of wealthy roués, all members of the Union Club, who organized frequent orgies in secret locations scattered about the city.”

White’s own great-granddaughter, Suzannah Lessard, goes further. He was a satyr who lost interest in a woman as soon as “all new sensations were exhausted,” she wrote in her 1996 tell-all, The Architect of Desire. Some victims were “barely pubescent,” and many were in “fragile social and financial situations — girls who would be unlikely to resist his power and his money and his considerable charm.”

One such girl was Evelyn Nesbit. With the approval of her mother, White struck up a “caretaking relationship” with the aspiring actress in 1901, helping her get a foothold in society. Not only did Evelyn go to the dentist at White’s expense — because he found bad teeth sexually off-putting — but he also moved the girl and her mother from a boardinghouse into a hotel. He provided Evelyn with a shockingly generous weekly allowance of $25, and, according to Lessard, plied her with expensive gifts, including “a large pearl on a platinum chain, a set of white fox furs, a ruby-and-diamond ring, and two solitaire diamond rings,” which he gave her on Christmas, which also happened to be her 17th birthday. The “relationship” seems to have lasted for six months, although they later remained on polite terms socially.

During Thaw’s trial, the world would learn that early in their acquaintance, White had invited the teenage Nesbit to his apartment for dinner. He poured her champagne possibly laced with a drug, then raped her after she passed out.

The Washington Times/Library of CongressCovering the trial, Mark Twain, a friend of the late architect, wrote that New York society had long known White was “eagerly and diligently and ravenously and remorselessly hunting young girls to their destruction… On the witness-stand, in the hearing of a court room crowded with men, [Nesbit] told in the minutest detail the history of White’s pursuit of her, even down to the particulars of his atrocious victory — a victory whose particulars might well be said to be unprintable.”

On February 1, 1908, Thaw was acquitted by reason of insanity and committed to a mental institution. White is interred in the St. James Episcopal Church Graveyard, near his Box Hill estate.

But Lessard, who grew up in a cottage on the grounds of Box Hill, writes that his debauchery runs almost like a genetic defect in the family. In addition to tales of cousin-rape, she said her uncle once kissed her in front of a group that included his own wife. As adults, she and five of her sisters recalled being fondled by their father.

As a Stanford White descendant, she wrote, “sexual violation was a condition of life.”