The following is an excerpted chapter from The Far Land: 200 Years of Murder, Mania, and Mutiny in the South Pacific by Brandon Presser.

On a gloomy afternoon in 1918, James Norman Hall stopped to buy a copy of William Bligh’s Bounty logbook from a dusty antiquities shop in London on his way back to America. A journalist by trade, Hall was working as a foreign correspondent in Europe covering the Allied air brigade during the First World War when he resigned his post and signed up for the French Air Force. Later, as a captain in the Army Air Service when the United States joined the fray, his airplane was gunned down over enemy lines.

“Many years from now, when this narrative is placed in your hands, you may wonder why I should have written it, with you in mind, long before any of you were born,” began Hall, thirty-one and unwed, in a letter to the grandchildren he hoped to one day have, written while he was held captive in a Bavarian castle as a German prisoner of war. He had befriended fellow inmate Charles Nordhoff, and after their release — Hall dreading the return to the tedium of his native Iowa — they moved to Tahiti, inspired by the grand adventure to the far side of the world that Bligh had detailed in his log. Hall married Sarah Winchester, the daughter of an American sea captain and his Polynesian wife, and together they had two children.

He continued his writing career with Nordhoff as his partner, and in 1932, the two men coauthored the first in a trilogy of novels that would catapult their bylines to international success: Mutiny on the Bounty.

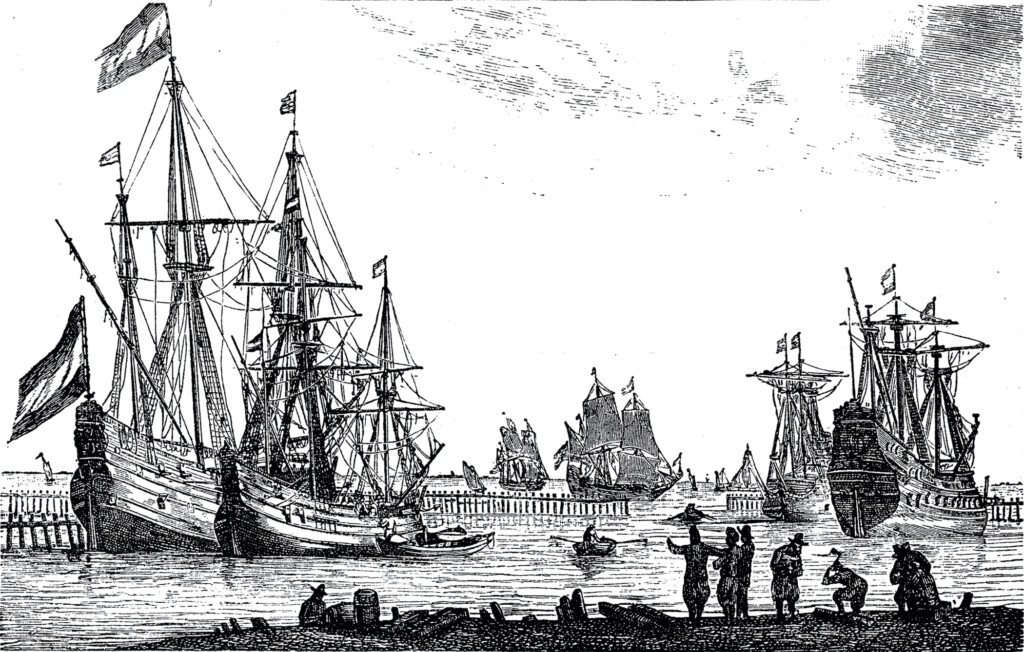

During the last decade of the eighteenth century, the story of the Bounty’s seizure had riveted audiences as each successive plot twist made front-page headlines the planet over. And the mutineers, who commandeered the little breadfruit-filled vessel after its departure from Tahiti, were the most wanted and notorious criminals in the entirety of the British Empire. But like all yarns spun through the loom of the news cycle, the true tale of the Bounty and its men had eventually faded to gray as other dark tales of the industrializing world soon spread across the globe.

Over a century later, Hall’s reimagined version of the events aboard the Bounty had stoked a refreshed interest in the subject matter. Soon, a legion of historians were delving back into Bligh’s logs and the journals kept by the other officers on board, to more properly decipher what exactly had happened in the deep of the South Pacific, three weeks after Mount Orohena had slunk below the waves.

Photo via Wiki CommonsSome academics found evidence that Bligh had quietly loaned Fletcher Christian some money during their stay in Cape Town en route to Tahiti, which had caused an ever-growing rift in their camaraderie.

Others speculated that the two men had become homosexual lovers and tensions flared when Christian sought out relations with several Polynesian women. But it was Hall’s romanticized version of the events on board — narrated by a fictitious crewman named Roger Byam (based on little Peter Heywood) — that would ultimately form the foundation of what most Bounty enthusiasts know today: a spat between Bligh and Christian over stolen coconuts that would send the young lieutenant over the proverbial edge, forever wrecking his naval career that was once so full of promise.

Like any good novelist, Hall dialed up the interpersonal drama as well, recasting Bligh as a sadistic and maniacal dictator instead of a haughty and hot-headed navigator. If there was ever a debate, Christian was now the unequivocal hero. His connection with Mauatua was largely exaggerated too — a grandiose romance between star-crossed lovers that would further contribute to the Bounty’s undoing.

Hall’s legacy — and the Bounty’s popularity — would continue to ascend well after the author’s death when, in the early 1960s, Hollywood eyed his Mutiny on the Bounty as the source material for its next blockbuster movie, casting Marlon Brando as the lead. Although it was the fourth film to immortalize this most famous of nautical events, the Brando version, made by MGM managed to add yet another layer to the mythos with its over-the-top production budget (the biggest in the industry to date, lavished on an exact replica of the ship) that became even more bloated when the shooting schedule was — like the real Bounty — hampered by severe rain delays. Also, like the real Christian, Brando began a widely publicized courtship with Tarita Teriipaia, the actress who played Mauatua. He would remain in the South Pacific after filming to embrace the castaway lifestyle as well — the two eventually married and had children.

The biggest impact of Brando’s Bounty, however, was its lasting effect on Tahiti’s tourism. The purpose-built complex that housed MGM’s production crew was later turned into the island’s very first resort, and the panoramic vistas captured on celluloid entreated audiences to come visit at a time when commercial air travel was really taking off, so to speak. Tales of Polynesia’s majesty had followed American soldiers home from the Pacific theater after the Second World War, and a surge of interest in tiki culture swelled with Hawaii’s statehood in 1959. The advent of long-haul flights shortly thereafter was the final piece of the puzzle to permanently position Tahiti as the ultimate tropical fantasy.

It’s rather fitting that the resurgence of interest in the Bounty’s story spawned our modern-day fetishization of Tahiti as holiday wonderland, because, in many ways, it’s a reverberation of the news of the actual mutiny back in 1789, which is largely responsible for solidifying the island-as-paradise narrative we know today. There are no mentions of a tropical island in the Bible — Eden was a garden, not an isle, of course — so the perception of paradise in the Judeo-Christian canon does not necessarily match our modern-day concept of palm-fringed beaches. Thomas More wrote of a perfect society on a faraway island in Utopia in the early sixteenth century, but it wasn’t until two centuries later — when French and British sailors made landfall in Polynesia — that the notion’s prevalence really came into being. In their logs, the explorers detailed an exciting and upside-down world relative to their own back in Europe. The warm Tahitian sun and cool lagoon breezes soothed their sea-addled bodies; the fresh fruit, plucked from practically every branch, cured their ails. Louis Antoine de Bougainville — the French contemporary of Captain Cook — dubbed Tahiti “New Cythera,” after the birthplace of Aphrodite, and wrote what was essentially an erotic tale of a pristine realm, bare-breasted women and all.

His account, along with many others, beguiled the upper classes back in Europe. They threw lavish parties with licentious Polynesian themes, pored over Joseph Banks’s detailed volumes of exotic findings, and displayed totems of the tropical world — like the pineapple — in their mansions for all to see.

Then, word reached the Old World that a group of young sailors were so moved by their extended time in Tahiti that they chucked their captain over the side of his ship in a desperate attempt to stay in Polynesia forever. And this — the frenzy aboard the Bounty — galvanized the synonymity of islands and paradise forever as news trickled down the rungs of society, captivating the world whole.

My time on Tahiti, however, had been anything but paradise thus far.

Traveling on a freelancer’s dime, I had opted for a rented room in a local home instead of an overwater bungalow at a resort while I waited to link up with Pitcairn’s freighter. Raiamanu charged me 15 euros a night for what turned out to be a cot in the corner of his living room, cordoned off by a long, hanging sheet draped over a string like drying laundry. The “you get what you pay for” adage had never rung so true.

Photo courtesy of the authorBut it was the rain that bothered me more — the hot, chunky rain that bore down on me like marbles, drooping the fabric of my dollar-store umbrella and rusting its metal spokes. This was not the dainty off-season afternoon drizzle that was touted in the online brochures. No, the rain was slowly drowning me with its perpetuity. The walls of Raiamanu’s house felt soggy and damp, as though mold or moss might suddenly flower out of its concrete pores. And the dull, cloud-ridden light hid all of the island’s wonders from view. Matavai Bay had been stripped of its silvery gloss, and Moorea’s green cathedral across the lagoon was shrouded in haze, its nave of palms and rocky spires — usually spotted from Raiamanu’s porch — were nowhere to be found.

On the third straight day of unabating storms — toes pruning in my sandals — I heard the squeak of a tin-can Peugeot as it inhaled the wet gravel up Raiamanu’s driveway. Kate Hall had come to rescue me from my Tahiti-on-the-cheap experiment gone horribly awry.

Through a long chain of friends of friends, I had managed to connect with James Norman Hall’s granddaughter — the eventual recipient of his future-thinking letter penned in war-torn Germany exactly a hundred years prior. Our spirited conversation over email had turned into an invitation to join her on her family’s private island, Motu Mapeti, before my imminent departure to Pitcairn. “It’ll be like castaway practice,” she joked as I climbed into her car.

In the backseat was a pink carry-on suitcase with wheels, which didn’t quite jibe with her tomboyish persona. Kate was a California surfer chick — slender, with sandy blonde hair and a permanent red smudge on the tip of her nose from too many years at the beach. She was in her fifties but could easily pass for much younger. Now living in Texas, Kate was the custodian of “Papa Hall’s” legacy, as she called him, and happened to be in Tahiti for a short week to deal with some estate logistics.

We slowly arced our way along Tahiti’s shoreline, getting bogged down by island traffic in Papeete, the capital. In Papara, we stopped at the fresh tuna market for provisions. “They know me here,” Kate announced emphatically as she slid through the door, though I could sense in her insistence that she wanted to belong to Tahiti more than she actually did. It endeared her to me, in a way, as someone who also grew up in a far quadrant of the former French Empire’s wilderness — Quebec. But I had left Canada at age fourteen and, like Kate, often clung to cultural touchpoints that were maybe no longer mine.

Inside, Kate was heckling the fishmongers, jockeying for the local price instead of the tourist fare. She cooed her gallic vowels and trilled her r’s just like the heavyset Tahitian mamies beside her who were vying for their turn at the counter. Kate did a double take when I chimed in too, equally surprised to find that French also hid under my veneer of American English.

Further down the island, Kate tucked her Peugeot under the shade of a large tree. The Halls owned the sliver of mainland adjacent to Motu Mapeti and had built a modest home for its caretaker, Terii, who came to greet us with a demure smile and a tiare flower drooping over her left ear. Kate briefly clicked back to English as we entered the home where Terii’s husband was watching TV in his wheelchair, gauzy bandages wrapped around his swollen ankles. “Diabetes has become a plague in Tahiti. He’s waiting for a liver transplant too.”

Terii had already carried our belongings down to the wooden dock in the backyard, which pointed directly at the island: a perfect little circle, like the tittle on a lowercase i, so close to shore that one could easily swim.

Ten minutes in a metal dinghy ushered us across the channel. We hoisted our belongings out of the boat, and Kate fidgeted with the zippers on her luggage. She soon exhumed what I would consider to be the single most random item one might pull out of a ratty pink suitcase on a sand trap in the middle of the Pacific: an Academy Award — its shiny bald head glistening in the sliver of sunshine that had managed to creep through the clouds.

“Wanna touch it?” Kate dropped the award in my carefully cupped hands. It was much heavier than I had imagined. “I seriously don’t know how those twig actresses can hold one of these up while giving their acceptance speech,” she chuckled as I read the inscription: To Conrad L. Hall — Kate’s father, James Norman Hall’s son.

Conrad had enrolled in filmmaking classes after trying unsuccessfully to follow in his father’s footsteps. “He got a D at USC’s journalism school,” Kate divulged. Eventually, he became one of Hollywood’s most acclaimed cinematographers, earning a total of ten Oscar nominations and three wins (the one I held was awarded posthumously for Road to Perdition in 2002). But first, while working his way up the ranks, Conrad had served as an assisting cinematographer — responsible for all of the sweeping panoramas of Tahiti’s splendor — on Brando’s Mutiny on the Bounty.

“Back in the 1960s, Motu Mapeti was only used for picnics,” Kate explained. “But Marlon loved to spend his time here in between shoots.” In fact, it was Motu Mapeti that enchanted Brando into buying an island of his own: nearby Tetiaroa (which incidentally was Churchill and Millward’s hideaway when they were trying to escape from Bligh).

Years later, in the early 2000s, Kate got a call out of the blue. “Hello Katie, this is Marlon Brando speaking,” she recounted, dropping her voice a husky octave to imitate the matinee idol. “I swear, I thought it was a friend pulling a prank on me,” she laughed. “Poor Marlon, no one ever believed it was him when he’d phone them.” Brando wanted Kate to help him find an engineer. He was going to build a lavish ecolodge on his island.

“That call began my year with Marlon Brando,” she explained. “He rang me every single day after that. He’d even show up at my doorstep to take me out to dinner.” Their relationship was purely platonic and, strangely, Brando never brought up his hotel aspirations again, preferring to discuss topics like Afropunk music instead. He died not long after.

Eventually, in 2014, a luxury resort was fully realized on Tetiaroa that rivaled the honeymoon bungalows of Bora Bora. Aptly named the Brando, the property quickly became a beacon for the jet-set elite; Barack Obama is said to have written much of his presidential memoir in one of the beachside villas.

Motu Mapeti, however, has remained a cherished secret of the Hall family, with very few luxuries or comforts. It has four flimsy huts and an open-air shower in the middle (read: a hose dangling down from a tall tree), just the way Kate’s father liked it.

And like her father, Kate had built a career in the entertainment industry, working mostly in documentary television. She moonlighted as a fixer for Survivor, saving the series when, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, plans to shoot the program’s fourth season in the Middle East were scrapped.

“An hour after the Twin Towers fell, I was on the phone with Mark Burnett — the show’s creator — suggesting that we reorient production to the South Pacific.” Kate was busy preparing our dinner of poisson cru, dicing raw tuna into small cubes, then adding salt, onion, cucumbers, parsley, and a generous amount of lime juice. Terii sat nearby on a strange piece of burnished furniture shaped like a giant tortoise: four wooden legs and a rounded blade with serrated teeth where the head ought to be. She scraped a halved coconut against the metal spikes as white shavings snowed down into a bucket below. With a cheesecloth, Kate then separated the coconut milk from its pulp, pouring it over the browning fish and tossing the contents with her hands. “When you really think about it,” she continued, “there’s no better spot than a small rock in a big ocean to capture Survivor’s awful duality of claustrophobia and isolation, right?”

She wasn’t wrong.

The “outwit, outplay, outlast” credo of Survivor’s interpersonal drama had riveted millions of viewers in the show’s first few seasons. The game seemed ill-suited to the pure of heart — apparently nice guys did finish last — but it didn’t necessarily reward those who were patently evil either. A new character archetype had emerged in the American zeitgeist, challenging the good-versus-bad duality that had long driven Hollywood’s plotlines. Antiheroes like Richard Hatch nabbed the title of sole survivor instead, not unlike the mysterious John Adams — the Bounty’s last mutineer, who outlived his comrades in a real-life version of Survivor. But the men and women of Pitcairn did things far, far worse than vote each other off the island.

The rain was holding out despite the overbearing grayness of the sky, so we took our dinner outside and sat on chopped logs. As the evening’s darkness set in, Kate gathered scraps of ironwood for a campfire, and from a single wick swiped from a soggy matchbook, the kindling burst into flames.

In the morning over cups of coffee, Kate finally broached the subject of Pitcairn. “It’s cursed you know. The place has bad mana, bad energy, bad vibes.” Interestingly, no one in the Hall family had ever visited the island. James Norman Hall’s only attempt ended in tragedy when his vessel was shipwrecked off Temoe atoll, some three hundred miles away. Kate seemed convinced that the Bounty cursed the souls that touched its story, and she began spouting off the evidence to support her claim. Brando’s life was plagued by tragedy after filming in the South Pacific. His portrayal of Christian was critically panned, sending his career on a decade-long downward spiral as he put on weight, saved only by turns in The Godfather and Last Tango in Paris, both in 1972. His marriage to Tarita soured as well.

Later — and worst of all — his half-Tahitian daughter was maimed in a car accident; she then hanged herself in her midtwenties after another of Brando’s children murdered her boyfriend in cold blood. Even MGM’s functioning replica of the Bounty carried bad luck in its sails; it had sunk off the coast of New York City during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, killing two crew members on board.

With more storm clouds closing in, we quickly made our way to the island’s beach and snorkeled in the graduating shallows to look for what Kate called “carrot shells,” like swirling unicorn horns coated in a pearlescent sheen. Home to a mollusk, as Kate explained, they hid under the ocean’s sandy floor. We swam the ten feet down to the bottom and returned to the surface each with a shiny shell in hand. Mine, however, didn’t seem to have a snail living inside, which Kate found slightly strange, as they usually became dull and brittle when abandoned. “A gift from Motu Mapeti, I suppose.” She encouraged me to keep it. Back on the beach, I placed the shell inside my snorkel mask’s plastic casing.

The next day, curled up on my cot in the corner of Raiamanu’s living room, my phone dinged with a new text message. It was Kate: “I told my aunt Nancy that you were heading to Pitcairn and she wants to meet you before you go. Do you have time?”

Like a moth to a flame, Conrad had sought out the bright lights of Hollywood, but his sister Nancy — James Norman Hall’s daughter — had stayed behind. She was now the doyenne of Tahiti. At fourteen she had met her husband, Nicholas Rutgers, while he toured the Pacific during the Second World War; she married him at 16. “Nick,” as she called him, was the heir to part of both the Rutgers and Johnson & Johnson fortunes. Kate had warned me, “Nancy lived a very, very charmed life.”

Her childhood home — the Hall family’s residence — was a breezy bungalow in the Arue precinct, down the road from Point Venus and Matavai Bay. As an adult, Nancy had purchased the sprawling acreage of hills just above it and constructed an elaborate estate overlooking the rest of the island. The original house down below was now La Maison James Norman Hall, a museum dedicated to her father’s memory that contained a trove of priceless artifacts including his desk, typewriter, a graft of an original Bounty breadfruit cutting destined for the plantations of Jamaica, and that hundred-year-old letter Hall had written to Kate without having known her name, framed near the entry to the gift shop. Often when Kate would visit, she’d bring along one of Conrad’s Oscars for temporary viewing.

The museum was about a twenty-minute walk from Raiamanu’s house. I carried an extra collared shirt in my tote bag, fully knowing that the one I was wearing would be drenched with sweat and rain before I’d even arrive. Nancy had arranged a private viewing of her father’s keepsakes — books, belongings, and photographs — after which I was invited up to her mountainside palace for lunch.

I threw my other polo over my shoulders in the museum manager’s car as we trundled up a serpentine path deeper into the compound. I felt as though I had finally reached the Emerald City, and yet my trip to Pitcairn — my real journey — hadn’t even begun. We drove by an empty in-ground swimming pool — its tiles cracked and claimed by weeds — and a nearby tennis court full of fallen palm fronds. Nancy had plenty of staff to ensure her property’s care, but in her late eighties she was interested in little more than eating, napping, and enjoying the views from the lanai. Her husband, Nick, I was told, had passed away less than two months prior, and I had begun to feel as though I would need to sing for my supper in an attempt to distract her from her newfound loneliness. They had been married for over seventy years.

“So you’re the Pitcairn boy,” Nancy, clad in a floral caftan, announced as she entered the parlor where I had been politely waiting. I immediately sprang to my feet.

“Sit! Sit! There’s no need to stand!” She pointed to a wicker chaise angled at a coffee table stacked with picture albums. For a while we admired dozens of black-and-white photos of a time gone by. Nancy was constantly hosting soirees over the decades, including the MGM film crew in the 1960s. “I used to give away black pearls as parting gifts,” she laughed. There was something about the directness with which she spoke, as though, at her great age, she no longer had the time to decorate her words with politeness.

When Nancy grew tired of reminiscing, she called out “Lunch!” — like Veruca Salt wanting her golden goose now — and an older Tahitian woman soon appeared in the doorframe to escort us over to the patio.

“This is Mele,” Nancy introduced us, “my daughter-in-law. Because,” she continued, “when your son diddles the maid and gets her pregnant, you make him marry her.” It wasn’t clear if Mele could understand her English, but I was nevertheless sure she knew exactly how Nancy felt.

One of Nancy’s younger attendants brought us each a halved avocado topped with minced shrimp slaw, served on bone china with a pewter teaspoon. For the greater part of the next hour, Nancy grilled me on my upbringing, schooling, and how I had — like her father — become ensnared in the Bounty’s trap.

“Do you want another one?” Nancy offered, tapping her hollowed-out avocado peel with her utensil.

“Oh, no I’m fine. Thank you though.” I thought a main course was about to round the corner from the kitchen, but that was it.

“I don’t like to eat very much anymore since my bones don’t allow me to do much moving around,” Nancy explained.

I grinned, famished.

“Well I think that’ll be all for this afternoon.” She cocked her head back and yelled “Nap!” into the air. Somewhere on the property, I imagined, there was a timid maid scurrying toward her bedroom to fluff the duvets.

Built-in shelving flanked the hallway connecting the manse’s public and private spaces, and before I departed, Nancy invited me down the passage to better admire her collection of books — all copies of James Norman Hall’s work. She pulled a pen out of her caftan, and each time she took a book down, she’d flip it open to its title page and sign it, as though she were her father’s proxy: To a dear young gentleman on his most excellent adventure.

I thanked her profusely but was quickly interrupted. “One more!” She reached for a paperback volume that was noticeably thicker than the others and plunked it on top of my growing stack of titles.

“The Far Lands,” I read the cover out loud.

“It’s a collection of myths and legends from all across the South Pacific,” Nancy explained as she watched me turn the first few pages. I started reading from the prologue: “The sight of any remote land in whatever latitude, though it be no more than a bare rock, still gives me something of a boy’s feeling of wonder and delight —” Nancy cut me off once more, “And you’re going to the farthest land of them all.”

The Far Land: 200 Years of Murder, Mania, and Mutiny in the South Pacific by Brandon Presser is available March 8